Trump vs. Universities: You’re Both Wrong

Also: which industries are Red vs. Blue, and science says being nice is more persuasive — BCB #145

American universities are under government attack in a way that they simply haven’t been before – a classic authoritarian move. That being said, universities really have become wildly politically unbalanced, reinforcing narrow-minded and sometimes harmful doctrines.

This is one of those things where both sides can be wrong at the same time, pleasing no one. But complicating the narrative is what we do, so let’s dig in. tl;dr pluralism is the most promising way forward for universities.

A few weeks ago, the Trump administration made a series of intrusive demands of Harvard – including that they have outside overseers to confirm that both faculty and students are “viewpoint diverse.” This is an unprecedented degree of top-down political interference in university life. When Harvard refused, the White House cancelled $2 billion dollars of federal research contracts.

All of the various attacks on universities have been framed in terms of efforts to combat anti-semitism, but given the sorry history of authoritarian government attempts to control education it’s easy to imagine that this is all just a pretense. More likely, anti-semitism is just a convenient narrative, useful because it has proven politically effective in taking down university presidents. Trump seems to fight any institution that might oppose him (see also his attacks on law firms, not exactly bastions of progressive ideology).

But even if the attacks are disproportionate, that doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem within universities. American faculty, especially at elite institutions, skew heavily Blue. Same goes for the student body; the vast majority of the schools surveyed in FIRE’s 2025 College Free Speech Report, for example, were liberal, and on those campuses the liberal-to-conservative student ratio averaged out at 7:1.

This is a trend decades in the making. Between 1990 and 2014, the number of professors who identify as “liberal” or “far left” rose while the number identifying as “moderate,” “conservative,” and “far right” all fell.

There are any number of explanations for how we got here (as we’ve covered before). Some say that the issue is an increasingly biased professoriate. Others frame it as a case of like attracting like, where people with more liberal views have just come to understand universities as places that will be hospitable to their ideas. Aside from exclusion, this ideological dominance inhibited inquiry and biased published science in some fields. We won’t rehash the excesses of “woke” here (it’s something we’ve covered previously) but they were particularly bad on campus.

Whatever the history, we’re now in a situation where universities are dominated by liberal people and ideologies, and conservatives have grown mad about their exclusion. The Trump administration has taken this to the extreme, but in doing so is also illustrating a pretty classic conflict dynamic: punishment all out of proportion to legitimate grievances.

But what then is the alternative to the White House’s current crackdown? In an excellent recent article for the New Yorker, Emma Green reported on efforts underway on college campuses to teach students to engage meaningfully with people with whom they disagree. She calls this “the pluralism pivot: a desire for a new paradigm that might ward off skeptical politicians and heal the bad vibes that have plagued higher ed.” Some are presenting pluralism as an alternative to now maligned and politicized DEI initiatives:

The model aims to help students live and learn together—making everyone feel welcome, and also helping students navigate the conflicts that inevitably arise in a community where people have different world views. Pluralism demands that conservative evangelicals who don’t believe in same-sex marriage be welcomed to campus alongside gay students, and that political conservatives who oppose affirmative action have fruitful discussions with people of color.

…

The intellectual framework of pluralism seems legally sturdier than that of D.E.I., which focusses on certain aspects of identity in a way that arguably runs afoul of America’s civil-rights laws. The Supreme Court recently banned race-conscious admissions, for example, and many colleges have moved to end race-specific scholarships after facing legal challenges. By contrast, pluralism emphasizes everyone’s ability to thrive, with all their differences fully respected.

Pluralism has been gaining increasing traction as a productive response to our current political woes. Whether this ideal can actually be achieved on campus remains to be seen. Green writes that those advocating for pluralism are alternately worried that their work will be seen as leftist by the right, and viewed by the left as capitulating to the right. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Where do red and blue Americans work?

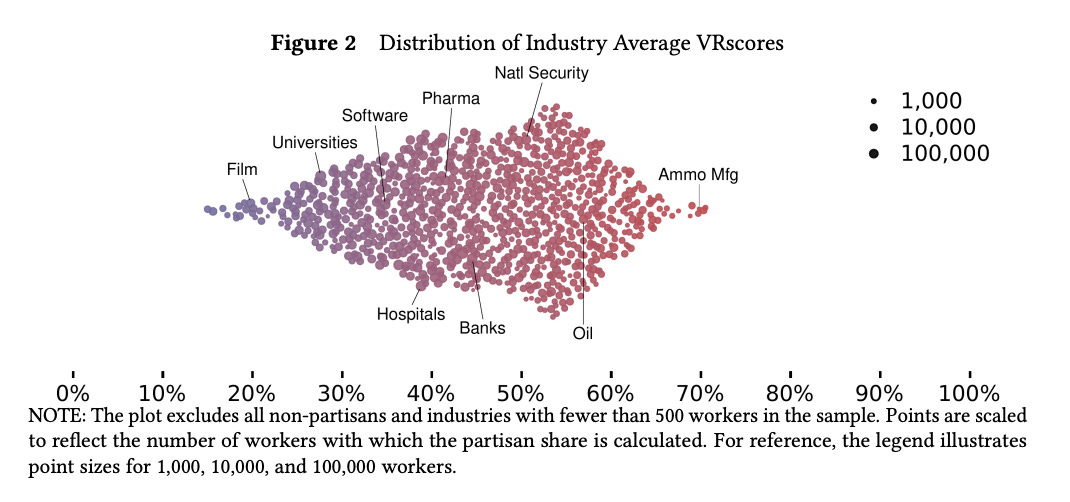

How do people’s personal politics shape the politics of their employers? This is one of those loaded questions that has long fascinated political scientists, who have typically used political donations as their main source of data. But recently, a team of researchers introduced VRscores, a measure of employers’ politics constructed from US voter registrations and online worker profiles between 2012 and 2022. Their project captures the politics of 21.8 million workers at 2.6 million workplaces, and finds that most industries tend to skew Blue.

Blue employees really do dominate health, media, government and technology. One thing the project makes clear is that, to quote Richard Hanania, “Republicans have a human capital problem.” Given that political polarization only seems to be increasing, this tool should help others answer questions about how workers shape their employers’ politics and ultimately society at large. To that end, they have made available a data visualization tool for exploring their work, and plan to release their full dataset soon.

Partisans are more likely to be persuaded if you’re nice about it

Sometimes science tells us that our intuitions are wrong (see: you don’t know how persuasive you are). At other times, it’s nice to have the obvious rigorously confirmed.

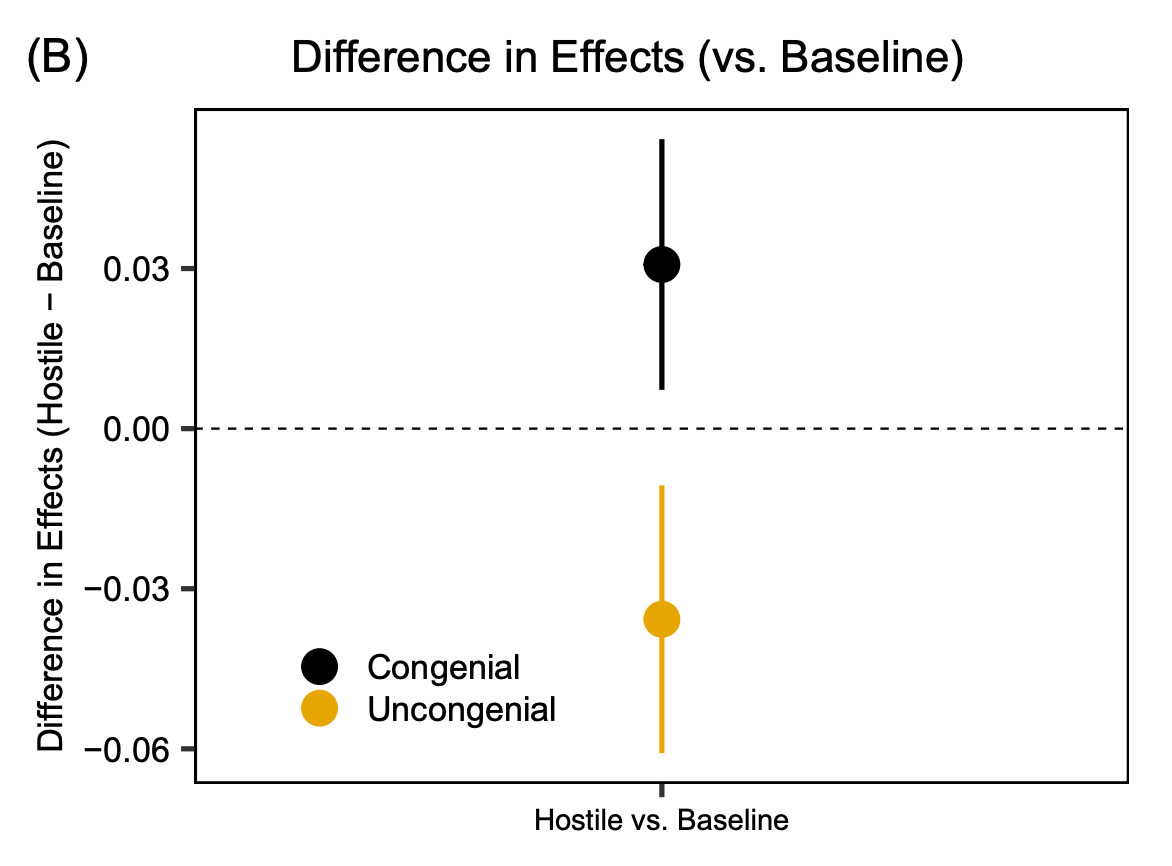

In a new study, researcher Jin Woo Kim looks at what circumstances tend to be most and least conducive to getting people to internalize information that challenges their partisan views. He found that both Democrats and Republicans could be persuaded by information that might seem “uncongenial” to them as long as, well, the persuader doesn’t say something that upsets them first.

As Kim put it in an accompanying thread on X,

resistance to persuasion wasn’t triggered by opposing info itself, but by the hostile context in which it’s encountered. This means two things can be true: (1) partisans are open to persuasion; (2) they often engage in motivated reasoning in today’s information environment.

To conduct this study, Kim recruited 4,506 people to complete a survey in which they answered questions about their attitudes towards the Affordable Care Act, partisan politics, and other demographic traits. Then he created an “adversarial environment” two different ways. First, he primed participants by asking them to write down either reasons they were dissatisfied with their own party (“ambivalence”) or reasons they preferred their party and disliked their political opponents (“univalence”). Second, he presented them with new information about the ACA in either a civil or uncivil way.

What he found was that those who received new information in a hostile context —that is, uncivil and/or univalent— doubled down on their beliefs and attitudes.

Among other things, Kim writes that this research underscores “the importance of the quality of elite-level political discourse in determining the quality of citizen-level opinion formation.” More fundamentally, it’s a helpful reminder that people are more likely to listen to you when you approach them nicely.

Quote of the Week

everyone’s lying down, ordering takeout, dissociating. the only rebellion left is to feel something unbearable. fall in love. write poetry. believe in God. be cringe. that’s punk now.

I've agreed with most of your posts about the problems of "cancel culture" on the Left, and the Left's intolerance for idea diversity. But this article leaves out a major reason why most university professors identify with the Left. (And by the way, most of the professors I know are also very critical of the Democratic Party, so there is more idea diversity on the Left than you acknowledge. Many of us are more Independents).

The Right doesn't just have a human capital problem. The Right has a science and fact problem. How could a university hire someone who doesn't believe in the basic science of climate change when 99% of scientists agree that it is caused by human activity? Or how could a university hire an economist or sociologist who doesn't understand that most migrants are hard-working, tax-paying contributors to the US economy? And here at Notre Dame, even Catholic professors understand that outlawing abortion is going to lead to more deaths and that the policy issues around women's healthcare are far more complicated than Republican policies allow.

The Right has abandoned science and fact, and this is why they are not represented in universities. As they say, the Truth has a Leftist Bias. Your point about pluralism rather than DEI is good -but in fact, this is already what many of us have done... we've substituted "pluralistic public problem-solving" for "democracy" and DEI because this administration has outlawed our language. Because your audience here is largely Left, it is natural for you to be harder on the Left and more lenient on the Right. But in this post, you've missed the opportunity to understand that universities don't want pluralism of ideas on whether science and facts exist.

We have to be careful not to pose democracy and fascist autocracy as "two equally valid ideas." Polarization is a problem, and we should address it. But fascism is also a problem, and as your post last week suggested, many of us in universities have been studying fascism for decades. We know that social movements - people power - are essential. So this week, when my university signed a letter with many other universities opposing Trump's plans for higher education, I hope you'll see this isn't a betrayal of our commitment to genuine pluralism. Sometimes I worry polarization and pluralism are overused words, that distract us from seeing the actual dynamics of what is happening.

Thanks for your thoughts. But I definitely do not think that policy options flow directly from science. As a political scientist, there are many factors that go into policy formulation. My point had nothing to do with this.