You Have No Idea How Persuasive You Can Be

Also: building islands not just bridges, and the potential of an abundance mindset. – BCB #140

How do you know whether an argument you’re making is actually persuasive to someone who disagrees with you? A new study has found that how convincing people think they are isn’t an accurate predictor of persuasiveness at all. But if that sounds disheartening, don’t despair! They also found that ordinary people are eminently capable of persuading others holding opposing views, even on famously contentious issues.

To measure persuasiveness between people, the researchers enlisted over 400 participants to write messages aimed at changing the minds of people who disagreed with them on three hot-button issues: immigration, the environment, and trans rights. These messages could be between 50 and 300 words—longer than a tweet, shorter than a Facebook post might be. Participants were given a cash bonus if their message proved persuasive, which meant there was an incentive to be compelling rather than to denigrate someone.

Senders were also asked to predict how persuasive their argument would be to someone who disagreed with them.

Once these responses were in, the researchers sent them out to a group of receivers. The researchers measured persuasion by the change in receiver issue opinion before and after reading the message. They found that nearly 30% of messages successfully shifted the receiver’s view in the direction of the sender’s, and only 11% had the opposite effect.

However, senders had essentially no idea of whether their arguments would be persuasive.

We asked [senders] to predict how many attitude scale points their argument would move the people who read it. … We use the same estimation approach as in the previous sections to determine whether Senders accurately predict their own persuasiveness. They do not. We find that Senders’ predictions about how much they will move Receivers is not a significant predictor of persuasiveness

…

Similarly, there are no significant differences between arguments [senders] expected to be less persuasive than average … nor those expected to be more persuasive.

So, what was an accurate predictor of persuasiveness? Many of the strategies that will be familiar to BCB readers. Arguments that sought to highlight common ground and bridge divides with the help of perspective taking and personal narrative were demonstrably persuasive. Evidently, if people learn to develop these approaches and skills, they can learn to become more persuasive to those who disagree with them, even on extremely polarizing subjects.

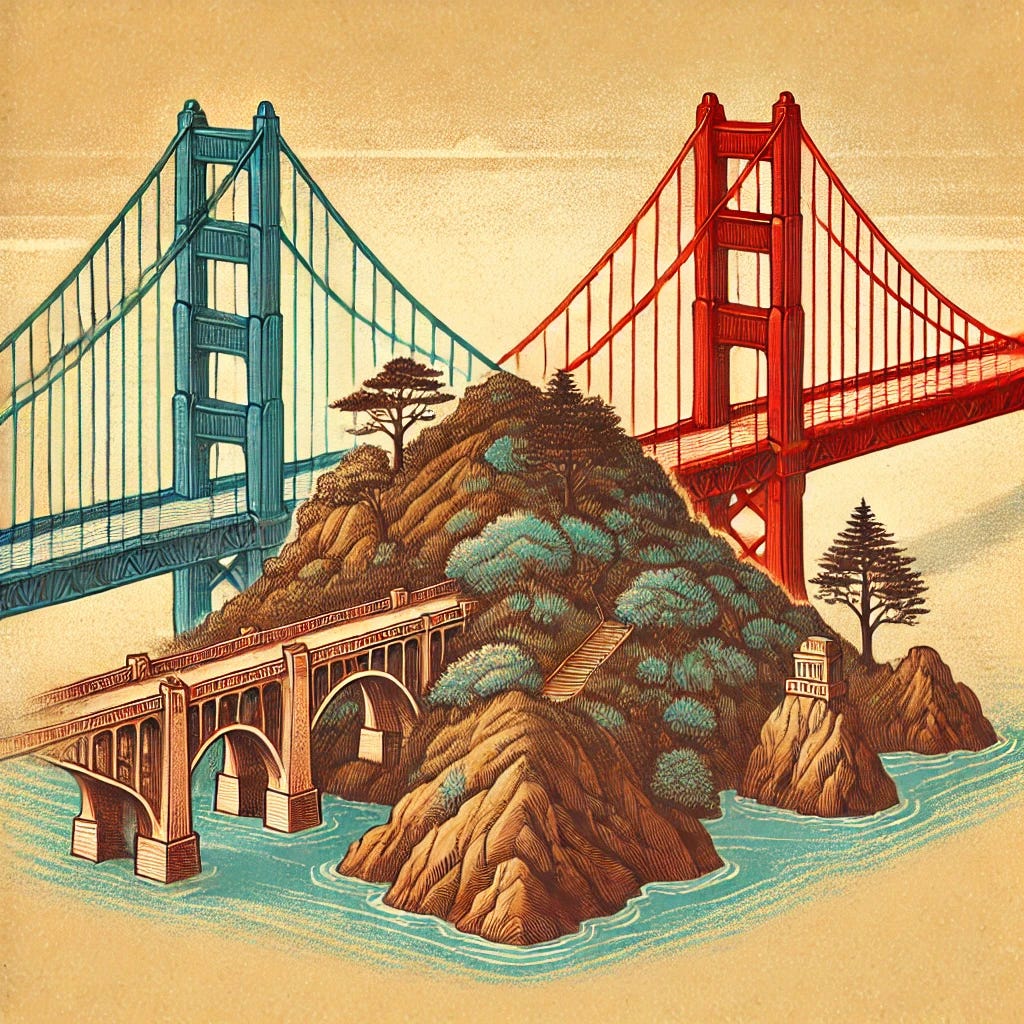

Building islands in addition to bridges

Is there any hope that bridge-building can be effective right now? This is a question at the heart of BCB’s work. “Are we fiddling while Rome burns?” ask Heidi and Guy Burgess.

In a recent issue of Beyond Intractability the Burgesses argue that while it seems unlikely that people from either extreme are going to meet all the way in the middle (at least not any time soon), it’s vital to keep creating spaces where people with opposing political views can come together to build something that has the potential to work for both of them. They call these spaces “islands”:

We need places in the middle where people can find agreement and maybe start building a society in which most all of us would like to live—a place where all sides can feel safe and be respected, be heard, and hear, and get refuge from the storm raging on both shores of the "mainland."

We’ve covered such “islands” before. They are often little-known and perhaps a bit scandalous (because, of course, peace-making is frowned upon by both sides). There’s that underground meetup for the cancelled in New York. An Israel-Palestine protest group that refuses to pick a side. Sometimes it’s just a comment thread where people are having a shockingly honest discussion about affirmative action.

Importantly, spaces like these also grant people the opportunity to understand their agency within our civil society. “We aren't just consumers of democracy. We need to be producers of democracy,” the Burgesses argue. The role of depolarization and bridge-building is not just to connect people but also to empower them:

Bottom line, we are trying to help our readers, listeners, and viewers to see that there is a way to build a future (a metaphorical island) on which democracy and its people can flourish, even as the mainland is suffering from a raging storm. And once that storm calms down (and we think it must, as all storms do), the islands of sanity—the islands of thriving democracy—will be there to provide models and help rebuild the mainland that temporarily lost its way.

To win, you need to deliver

For a while now, both parties have been peddling a scarcity mindset. Blue has leaned full-tilt into regulation and dwelt on the importance of rationing resources, while Red has become increasingly anti-immigrant and opposed to scientific research while harkening back to a bygone era. But scarcity doesn’t provide a path forward and out of our current political quagmire. What we need is abundance: more infrastructure, science, energy, business, innovation, education.

At least, that’s the argument that Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson make in their new book, Abundance. While the authors lean left and have written a book that is addressed to discontented liberals, the points they make are relevant across party lines. As fintech investor and internet personality Sheel Mohnot pointed out after hearing them speak:

the Abundance mindset isn't partisan—It’s the progressives dream of immigration and affordable housing, libertarians push for free trade and deregulation, conservatives love of American greatness—and a rejection of zero-sum thinking from all sides.

In a New York Times video essay pegged to the release of his book, Klein dives into some examples of how Democrats have failed on this front in recent years. He explains how astonishing regulatory hurdles and the associated astronomical expenses have hobbled projects like California’s plans for a high speed rail running between Los Angeles and San Francisco, and how red tape has prevented the development of more housing in places where the cost of living is high—many of which are, incidentally, Democratic strongholds—and subsequently driven Americans to move elsewhere.

Right now, he explains, it feels like we live in a country where important infrastructural improvements never come to fruition and housing is meager and expensive. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

The answer to a politics of scarcity is a politics of abundance, a politics that asks what it is that people really need and then organizes government to make sure there is enough of it. That doesn’t lend itself to the childishly simple divides that have so deformed our politics. Sometimes government has to get out of the way, as in housing. Sometimes it has to take a central role, creating markets or organizing resources for risky technologies that do not yet exist.

This argument is compelling. Delivering improvements that make people’s lives better—and make them feel better about their lives—certainly sounds like a winning political strategy. What Klein and Thompson offer is a pragmatic Blue take on improving conditions for everyone. While their take has a partisan bent, the point they’re making is one that offers the potential for bridge-building in the long term.

Quote of the Week

they don't want you to know this, but "woke" has a definition that's both useful and captures most of common usage: it's "illiberal progressivism."

so "anti-woke" was a strange coalition: some were opposed to the illiberalism, while the rest were opposed to the progressivism

Thanks, Eve and Jonathan for your highlighting our BI post! And the persuasion piece is fascinating too!