Why Are Academics Liberal?— BCB #108

Also: bridge-building groups to look out for, and protesting isn't change by itself

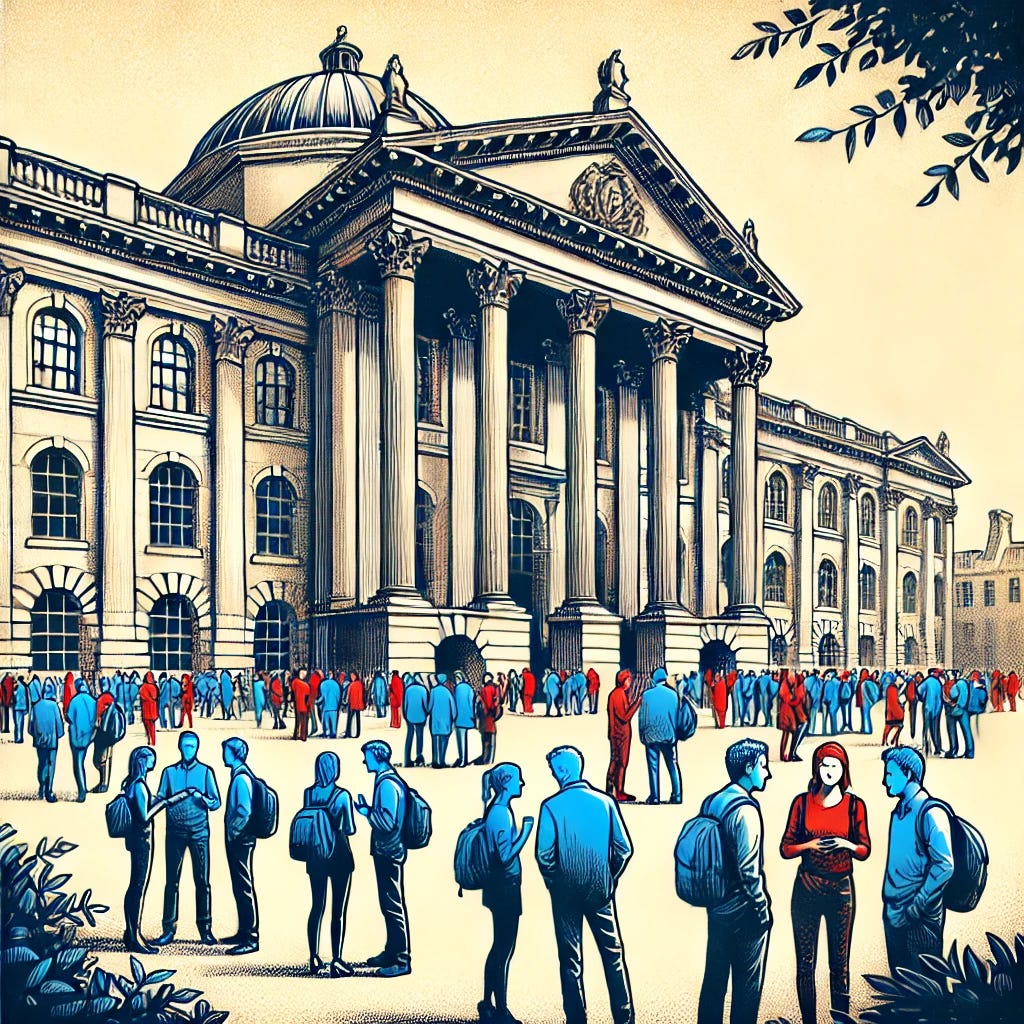

Why aren’t there more conservative academics?

It’s no secret that professors skew whiter, Bluer, and less religious than America at large, as sociology professor Musa al-Gharbi has pointed out. Whether or not this is a problem is an issue that has been hotly debated. But in a recent piece for National Affairs, political science professor Steven M. Teles asks a more fundamental question: why are there so few conservative faculty members at American institutions in the first place?

There are two popular theories explaining why there are so few conservative and religious scholars in academia. As al-Gharbi explains in a thread about Teles’ essay:

1. They face discrimination on the job market, and a hostile work climate if they are employed.

2. They would rather do other things with their lives.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. The frameworks Teles uses to analyze the dearth of Red scholars are drawn directly from long-established social justice ideas of how a particular group of people are excluded. And there’s research indicating that liberal scholars will discriminate against their conservative colleagues. While the true extent of such discrimination is unknown, just the perception can discourage would-be conservative scholars.

Liberal readers may be uncomfortable with this analogy. Conservatives are not “historically marginalized,” and for some this is a very big difference. Some conservatives are also uncomfortable with the social justice analogy, but for different reasons. This, al-Gharbi says, is where things really get interesting:

We have frameworks to explain how we can have systematic underrepresentation and exclusion even in the absence of actual discrimination. Conservatives tend to hate them.

But, ironically, understanding ideological representation in the academy through the lens of systemic and institutional discrimination can explain the observed patterns far more comprehensively than either of the most discussed hypotheses at present.

In fact, it can help unify those hypotheses — taking the most compelling evidence for each while addressing their apparent shortcomings.

To repair and balance out the composition of the American academy, Teles writes:

… conservatives and academic leaders may need to move simultaneously, with academic leaders committing to costly, visible signals of openness and conservatives accepting those signals and amplifying them rather than receiving them skeptically.

This is a fairly obvious point—if we want more conservatives in the academy, that will take specific and sometimes difficult action, in very much the same way that specific work is needed to ensure representation among other marginalized groups. The real argument is about whether universities should try to match the ideological demographics of the country.

Teles says they should. He argues that “liberal institutionalists”—people who believe staunchly that “the university should be institutionally neutral,” a group which he counts himself a part of—must do their part to make their institutions more ideologically open.

Bridge-building groups to keep an eye on

The New York Times recently ran a feature story on polarization, highlighting the work of many groups and funders in the bridge-building space. Polarization has long been a mainstream concern, but solutions to polarization are just starting to break through.

The Kentucky Rural-Urban Exchange, for example, was founded in 2014 to bridge divides in the state and has hosted two annual weekend meetings, one in a rural area, every year since. At these meetings, 60 people with a wide range of ideological perspectives from across the state get together and learn from one another. The goal is to brainstorm and share, to talk about politics less.

Other groups are more focused on figuring out how to foster dialogue specifically around politically divisive topics. NewGround, for instance, is an organization that focuses on facilitating dialogue between Muslims and Jews about and beyond the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And BridgeUSA “champions viewpoint diversity, responsible discourse, and a solution-oriented political culture” on 65 college campuses across the country.

Funders are also turning to depolarization initiatives. As Stephen B. Heintz, the president and chief executive of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, told the Times:

We have to be focused on what we call the exhausted majority — that’s 65 percent of Americans… It’s just not an efficient use of time to convince true ideologues to compromise.

How not to fall into the “protest trap”

Today, many people seem to think that the way to make the world better is to pick a side and speak loudly against things you find troubling. There are plenty of reasons to protest beyond creating change—finding community, airing grievances. But if you speak out about something without also presenting some kind of solution, you run the risk of falling into the “protest trap,” writes Amanda Ripley:

We get so seduced by the magnetism of the demonstration itself that we start to really believe that the protest is the change. It’s a form of magical thinking, the kind that is very hard to resist in an age of high conflict.

Okay, well then how do you make sure that a social movement is successful? Ripley summarizes a 2022 write-up from the nonprofit Social Change Lab, which identified three things that tend to make protest movements worthwhile:

1. Nonviolence. Like others, they found that nonviolent movements are significantly more likely to lead to change. In their book Why Civil Resistance Works, Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan concluded that nonviolent movements were more than twice as likely to succeed as violent ones. That’s largely because of No. 2.

2. Large Numbers. Size really matters. The more people you attract to your cause, the more likely change will happen. Nonviolent, flexible movements can attract and retain larger, more diverse followings. (Because violence, by contrast, is scary, and many mentally stable people tend to disengage when they see it.)

3. Timing. Most of the levers of change are outside the control of the protesters. Public opinion, media attention and luck can create openings, all of a sudden. So it’s important to organize in advance, so you can seize those openings when they happen.

Attention alone doesn’t lead to change, Ripley points out. The most successful social movements also take the power of relationship-building seriously, creating webs of people who trust and feel a sense of kinship with each other.

Quote of the Week

Relationships are the root and the flower. They are the point at which social infrastructure creates infrastructure for anything to happen… When you look for common ground you find it, but conversation can’t be about conversion.

— Savannah Barrett, co-founder of Kentucky’s Rural-Urban Exchange

I'd like to suggest one more options for why academics skew liberal.

Suppose the experiences of being or becoming an academic tend to increase liberal opinions; alternatively, other career experiences tend to increase conservative opinions. (Youth tend more liberal than their elders; perhaps academics simply preserve youthful opinions longer.)

The offensive/blindly-blue version of this would be even simpler. "Academics are more prone than most others to be interested in discovering truth, and truth skews blue." My twenty year old self would have suggested that unhesitatingly, except that the blue-red metaphor wasn't then current. As a senior citizen, I'm not so sure of either part of this explanation. But it does seem like the elephant in the room, particularly when I hear of red lawmakers passing laws based on medical falsehoods they don't care to reality check. (In what world is it impossible to be impregnated by rape?!?)

The testable version of this would involve a longitudinal study of aspiring academics, and not include just-so stories explaining the reason for any difference found.

I'd also be interested in comparing changing political opinions of aspiring academics who succeed with those would-be academics who wind up in different careers.

It might also be interesting to disentangle the various components of blue and white politics. From where I sit, believing in a tangible, world-influencing deity is less compatible with a research orientation, than believing that it's a great idea for your own group to have most of the wealth and all the political influence. (Selfishness is not incompatible with a search for truth.)

because "the more you know"...