Why Build Bridges when Democracy is Burning?

The only way to win is for "us" to ally with some of "them" - BCB #165

Last Sunday, 1,400 people attended Dignity over Violence, an online gathering hosted by 26 different bridge-building organizations in the wake of the Kirk shooting. Community organizer Micah Sifry wrote this about it:

I listened carefully to all the speakers, hoping to hear someone say something about the rising danger of authoritarianism under Trump. But everyone stayed in their imaginary middle, where both sides in our polarized country supposedly have equal amounts of power to do damage to the civic fabric. No one mentioned the many ways the Trump administration has broken the norms of democratic governance, from pardoning all the January 6 insurrectionists to using the massive power of the Justice Department as well as the federal purse to coerce universities, law firms, media organization, and faith institutions to bend to its ideological agenda.

I’m not picking on Sifry — he’s a smart progressive voice and we’ve featured his work before. Many people would agree with him that Trump really does pose a genuine threat to democracy. (So many others have articulated why that I’m not going to bother making that argument here.)

Of course, for many of you this may be galling to read. In that case you may feel that Kirk’s assassination and the response to it shows anew why the left cannot be trusted with the nation’s institutions. (Again, it’s not worth presenting the argument for this here. It’s everywhere.)

In fact 80% of Democrats and 40% of Republicans currently feel that democracy is in danger (this was more even last year before the election.) They disagree about what that danger is, sometimes vehemently. But even if you think that it’s entirely the other side’s fault, I would still say that bridge-building is essential.

The goal of bridge-building is political, but it’s not to promote progressive or conservative politics. That's the job of progressives and conservatives. The goal is to have a functioning democracy where conflicts are resolved without violence or destruction. There are many ways to support this (see 53 Roles that Make Democracy Work) but the overarching strategy is to create a coalition big enough to successfully defend democracy.

Us and Them against Tyranny

Even if it’s true that one side presents a clear danger to our democracy, this message has been shouted from the rooftops for years. It did not prevent Trump from winning an election. It did not prevent BLM violence while NPR approved. I don't see why shouting louder about the danger the other side poses will be successful now.

You don’t have to think these two threats are of equal magnitude or significance to appreciate that for every reasonable person on your side there is a reasonable person on the other side who fears the opposite. It is characteristic of closely contested conflicts that both sides think they’re losing, and America has been in a period of remarkably competitive presidential elections for decades now.

The extremists of any stripe are still marginal — yes really, see below. The problem, as I see it, is what the wackos on each side can get away with because of their enablers.

Trump can get away with dismantling democracy because far too many people are so angry that they support him. And whether you’re angry about the CDC’s handling of COVID, the “defund the police” movement, or the censorship of the Hunter Biden laptop story, these things were possible because of pervasive left culture within many American institutions. Again, this comparison will seem like an outrageous false equivalence to many people. That’s exactly the problem — we’re too mad at each other to build a big enough coalition to solve the country’s very real problems.

If this analysis is correct, then the winning strategy — winning in the sense of democracy-preserving, not advancing either Red or Blue politics — is for “us” to unite with some of “them” against authoritarianism and corruption of whatever stripe.

We’ve said this before. This strategy is sometimes called “repolarization.” The goal is to change the axis of conflict, not to remove or suppress conflict. This has been explicitly expressed by, among others, political scientist Jennifer McCoy, whom I recently interviewed.

History shows that moments of high polarization are moments of high volatility. Our country may change very quickly either for the better or the worse. To make this change positive, we need a new political coalition that is for something, not just against Trump or against liberals. What that something is remains to be seen. “Democracy” will no longer unite us, because that word means too many different things to different people. But perhaps “freedom”, “abundance,” “opportunity” or “honest institutions” might. Or perhaps even “preserving our ability to disagree and have it matter,” the most fundamental form of political freedom.

In terms of actual governance, there already exists an eclectic mix of left and right policies that large majorities support. You probably dislike some of these. But could you live with them for the good of the republic?

Bridge-building with Red and Blue characteristics

Progressives are starting to articulate why they need to ally with some of their erstwhile enemies.

Shikha Dalmia made this case at the recent “Liberalism for the 21st Century” conference, in her opening address titled Liberals Need Moral Clarity, Not Moral Purity, in Their Struggle Against Authoritarianism:

we need to fashion a broad countermovement to replace the old right/left divide with a new liberal/illiberal one, as I tell anyone willing to listen. That means opposing bigotry and uniting around core liberal values: tolerance, pluralism, equal protection under the law, and accountable rulers. …

Building a liberal coalition requires getting former political foes to learn to trust one another and negotiate their inevitable moral disagreements.

We’ll have to overlook what we regard as each other’s past transgressions. We’ll have to live with disagreements over whether non-right-wing threats to liberalism are worth addressing, or mere distractions. We’ll have to thrash out differences over how much to concede to our opponents to secure electoral victories. That seems like a strategic issue but often strategic disagreements stem from different levels of commitments to competing moral values.

That sounds like bridge-building work to me.

Another source of inspiration for me is john a. powell's article Overcoming Toxic Polarization: Lessons in Effective Bridging, which explicitly discusses how power imbalances relate to bridge-building work:

Many activists and community organizers are predisposed toward skepticism of bridging and perhaps even the larger theory of social capital. Part of the reluctance is grounded in the foundational position of power building that is core for many activists. …

It is only a slight exaggeration to suggest that at one pole there are those calling for bridging without addressing power to be the principal way to solve polarization. At the other pole is the rejection of bridging either outright or to load up the preconditions for bridging so that it effectively makes bridging a complete nonstarter. It is these positions that this Article attempts to resolve by suggesting other possibilities.

Powell’s article also discusses the role of race in polarization, and the ways that conservatives are marginalized. It’s really quite a synthesis, again from the progressive point of view.

When I talk to bridging leaders they universally tell me they do not see as much active reaching across the divide from the Red side. Cynically, it’s easy to say that this is because the Right is in power now so they have no need of reconciliation, while the left is only playing nice because they have no other option. However, we also saw this same asymmetry during the Biden administration. I’m not sure it’s worth having the inevitable argument over whether this is due to the stubbornness of conservatives or the liberal bias of the professional classes that most bridge builders come from. I’ll only say that this is a crucial challenge.

There are important exceptions. In the aftermath of the Kirk shooting, Republican Governor Spencer Cox of Utah delivered one of the most powerful pleas for understanding on the right.

He said,

Over the last 48 hours, I have been as angry as I have ever been, as sad as I have ever been. And as anger pushed me to the brink, it was actually Charlie’s words that pulled me back. I’d like to share some of those. And specifically, right now, if I could, I need to talk to the young people in our state, in my state, and all across the country. As President Trump reminded me, he said, “You know who really loved Charlie? The youths.”

He’s right. Young people love Charlie, and young people hated Charlie. And Charlie went into those places anyway. And these are the words that have helped me.

Charlie said: “When people stop talking, that’s when you get violence.”

…

History will dictate if this is a turning point for our country, but every single one of us gets to choose right now, if this is a turning point for us. We get to make decisions. We have our agency. And I desperately call on every American — Republican, Democrat, liberal, progressive, conservative, MAGA, all of us — to please, please, please follow what Charlie taught me.

Correcting misunderstandings

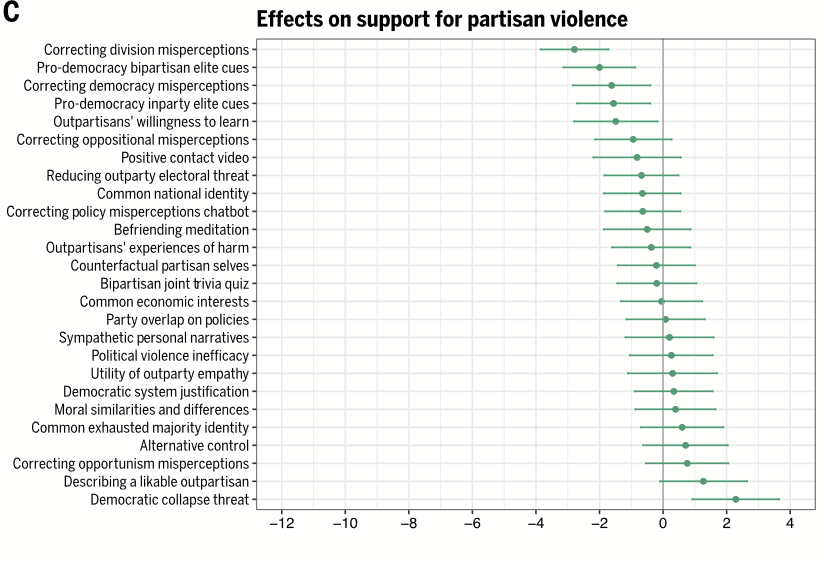

Recent research suggests that the second best way to reduce support for partisan violence is for bipartisan political elites to condemn it. Thankfully, this is happening (with notable exceptions, especially among media figures).

The first best way to reduce support for political violence is to correct misperceptions. Conflicts don’t always arise because of competition over resources or power. They can also happen when the sides misperceive each other, and Red and Blue misperceive each other very badly indeed. Each side thinks many more people hold extreme opinions than actually do, a problem called the perception gap. It’s a 20-30% gap across many different issues, nearly symmetric on left and right, and the inflated perception of support for violence is particularly acute:

Democrats think 45.5% of Republicans support partisan murder, which is 20.7 times larger than what our data show. Similarly, Republicans think 42% of Democrats support partisan murder, which is 25 times larger than reality

The best estimates come from large and careful surveys, and they show that 2.1% of Democrats and 1.8% Republicans would support the murder of a political opponent. 3.9% of Democrats and 3.3% of Republicans would support other forms of violence, like assault or arson. (Random surveys showing much higher numbers are probably not trustworthy, because of inattentive answering and unclear questions.)

And of course, each side over-estimates the other side’s willingness to subvert democracy. Which makes them more likely to subvert democracy first!

There are many ways to correct misperceptions about people from the other side — who we have less and less casual contact with — but one of the best is simply to talk to them. Of course, not all talk is created equal. Communication across deeply felt divides requires facilitation to ensure a positive experience. This is exactly what the hundreds of bridge building organizations across the country do.

Quote of the Week

I have to admit. You’ve persuaded me that neither the right nor the left can be trusted with protecting civil liberties.

So, alas, it seems the only solution is a system of checks and balances on limited govt with a federal govt with only specifically enumerated powers.

Nice response to Micah, Jonathan. I'm generally a fan of Micah's blog, but this was not his best moment and you explained why much more constructively and charitably than I did.

Dear Jonathan,

Great piece. Mahalo.

I've worked in the bridging/transpartisan space for many years, including efforts to help build a new constituency -- a third side to use William Ury's language -- a new political force. Have you seen the recent piece by Diana Smith?

https://remakingthespace.substack.com/p/code-blue?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=2233175&post_id=172802093&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=3nw100&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

I'd welcome a conversation if that works for you. johnasteiner3286@gmail.com

Very best,

John Steiner

co-founder the Bridge Alliance

Board member Mediators Foundation/Better Together America