Why Do They Think We're Extreme?

Where do partisan stereotypes come from and how can we deflate them? — #150

While it’s easy to name extreme political positions (like “defund the police” or “deport all immigrants”) we all wildly overestimate the number of people on the other side who hold them — by 20 or 30 percentage points. But why? And can we do anything about it?

This isn’t a question about political leaders. It might be reasonable to call Trump “extreme,” or perhaps AOC. But I’m talking about what we think of other citizens, and they’re not nearly as riled up as one might imagine. This distinction is important, because having good relations with citizens across the divide is key to defeating extremism of all types.

More in Common has a beautiful visualization of the problem (as of 2019). This chart shows what Blue thinks Red thinks. For example, about 70% of Republicans would say that “Many Muslims are good Americans,” but Democrats guess that only 40% would say so.

This effect is not only large but fairly symmetric. Here’s Red guessing what Blue thinks:

Political scientists call this sort of thing “meta-perceptions,” or people’s perceptions about the other side’s perceptions. More in Common calls the difference the perception gap. There are many other ways that each side negatively stereotypes the other, such as believing they’re much more willing to engage in political violence than they actually are. Reducing the perception gap — by better informing people of what the other side actually believes — has proven to be one of the most effective ways to reduce polarization. Or if you like, it reduces “overthreat,” our outsized perceptions of danger.

But why does this gap exist in the first place, and why is it so large? Why do they think we’re extreme? I don’t think anyone knows for sure, but I have a pretty good guess: Americans are having fewer and fewer cross-partisan relationships, and most of our “contact” with the other side is through exaggerated media.

Media favors the extreme

The most partisan politicians get the most media coverage. Stands With US demonstrated this with their analysis of who got the most media coverage in the 2022 elections, finding that “hyperpartisan” politicians got four times more coverage.

Social media also amplifies emotional, threatening and negative content. One 2021 study found that discussions with a positive or negative tone got more engagement than neutral discussions, but negative discussions about “them” (the opposite party) got the most engagement by far.

Our political media diets simply do not represent reality, showing us a distorted, much more extreme and threatening view of the other side.

We’re politically segregated

You’ve probably seen maps like this, showing how voters self-segregate. Blue lives in the cities, Red lives in the country.

What you might not know is that this geographic segregation continues right down to the level of individual houses. A 2021 study examined 180 million registered voters, finding that

For both the median Democrat and the median Republican, only about 3 in 10 of their interactions in their residential environment will, on average, be with a member of the other party.

..

A large proportion of voters live with virtually no exposure to voters from the other party in their residential environment.

It’s therefore not surprising that we don’t have that many cross-party friendships, and fewer than we did before.

In short, we misunderstand and fear each other because we consume distorted media images of people we mostly never meet.

What to do about it?

The large scale solution would be to reverse partisan sorting and/or change how media works. Although there are things that can be done — I’m researching depolarizing social media algorithms — it’s going to be hard and slow to make such massive changes. We have these effects because there are strong incentives toward them, after all.

Instead, consider changing your own media diet. If something makes you angry or afraid, stop to ask whether that’s a fair representation of the other side, or an extreme example. For more, consider doing the four week Polarization Detox Challenge.

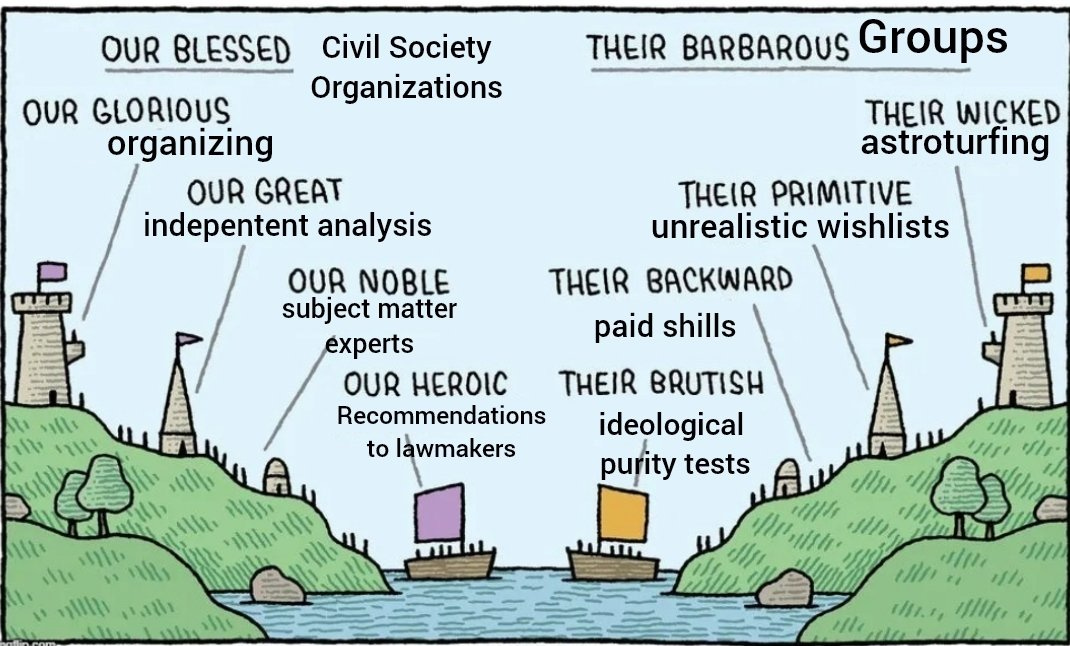

Image of the Week

- @maiamindel

Funny, I have no clue what my neighbor's political registrations are, or, in most cases, their political leanings, other than the R-14 breakdown of my huge western Loudoun County, VA, precinct. We don't talk politics or let them divide us. We're more focused on the debacle being created by an incompetent majority on the Purcellville Town Council. And I have no idea what their partisan leanings are, either.