When to Fight and When To Talk

Should you be a lover or a fighter when justice is on the line? – BCB #155

Every conflict eventually raises the same question: do we fight harder, or do we listen better?

In May, Donald Trump stood beneath a massive banner in Qatar: “Peace Through Strength.” This is an old idea: it’s the threat of force that keeps conflict at bay. It’s also the central idea of power-based activism strategies: it may take organized pressure—economic, reputational, or political—to bring others to the table.

And yet, the central message of many traditions of conflict resolution is that we should listen more and fight less. How do we square these two ideas, especially when we feel our enemy is causing real harm that must be stopped?

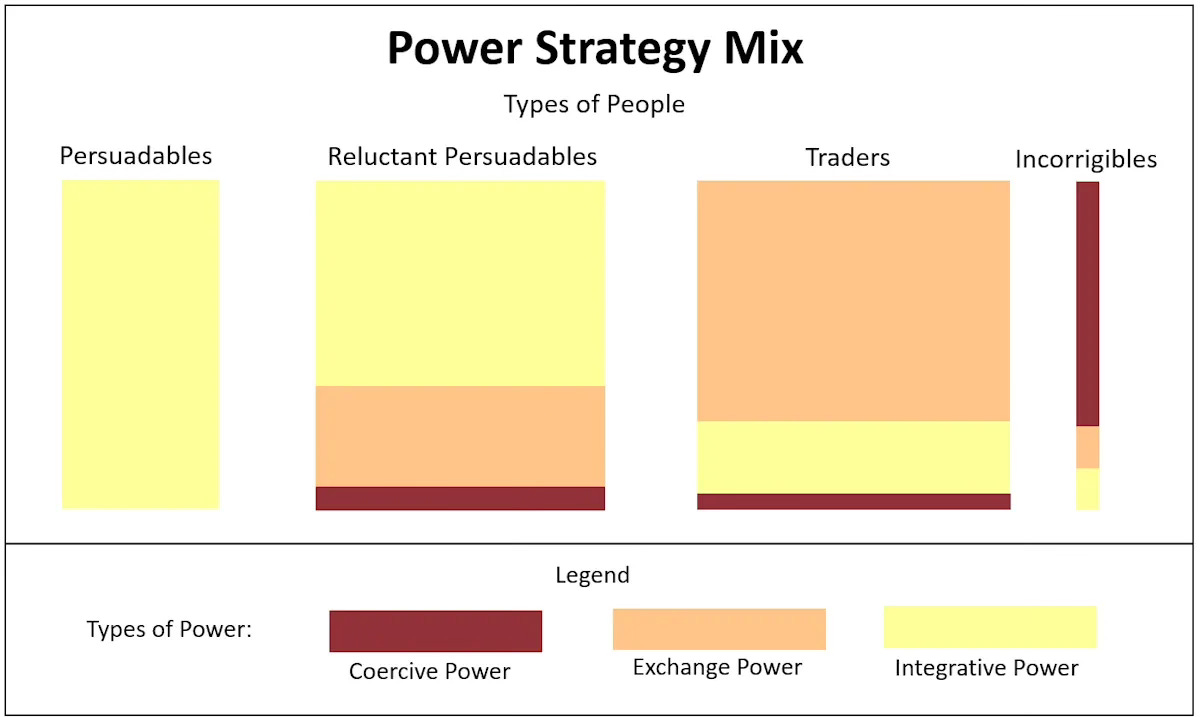

We asked this question to Beyond Intractability writers Heidi and Guy Burgess a few weeks ago, and they directed us to the “power strategy mix.” The core idea is that there are different kinds of people and situations that call for different kinds of power.

These types of power are:

Coercive: "Do this or there will be consequences that hurt you."

Exchange: "Let’s make a deal."

Integrative: “We’re in this together – be it through love, shared values, or some other source of legitimacy.”

In practice, most real progress comes from a mix of these. But – and this is the other key point – your adversary is not monolithic! There are different “audiences” in any conflict, and each responds best to a different form of power.

We’ve written before that if you want to “fight” authoritarianism, it’s vitally important to distinguish between regular citizens and hard-line political leaders. That’s true in other high-stakes situations too.

Reading the room wrong

If you diagnose a situation and an “opponent” correctly, you can then correctly prescribe the appropriate power strategy mix for the situation. According to Beyond Intractability, most opponents will fall into one of these four categories:

Persuadables: they largely share your values, just need some convincing → respond best to integrative power

Reluctant Persuadables: these people are open to your ideas, but they’ll be more cautious→ need a mix of integrative + exchange power

Traders: these people are not aligned with you, but they will be willing to make a deal → mostly exchange power + some integrative

Incorrigibles: Hostile, bad-faith actors → require coercive power

The problem is that we’re much worse than we think at telling these groups apart. Surveys show that Americans consistently overestimate how extreme the other side really is. And the more involved in politics we are, the worse our estimates get! (Heavy media consumers are 3x less accurate about what opponents believe).

When this happens, we’re likely to label “persuadables” or “pragmatic traders” as “incorrigibles” and to reach for coercion as the conflict strategy of choice when cooperation or persuasion might have worked a lot better.

The result? Backlash. Suddenly, the people who were within your reach and willing to inch closer are now further away than ever. You lose not just the argument, but also the relationship.

Power strategy in practice: Trans rights

We are seeing this strategic debate playing out right now around trans rights, as we saw in last issue’s coverage of the strategic disagreement between Erin Reed and Sarah McBride. Some on the left argue that some things are non-negotiable – that to dignify certain views is to legitimize harm. Others say that this approach has backfired as public support for trans rights has fallen in recent years.

Perhaps the solution to this argument is to recognize that there are different “audiences” which require different strategies. Sarah McBride, the first openly trans member of Congress, doesn’t waste time “debating the other side.” But she also doesn’t treat the public as hostile. “We’re not negotiating with the other side,” she says. “We’re negotiating with public opinion.”

That distinction matters. It assumes most people aren’t immovable or malicious—they’re “reluctant”. And reluctance is a very different thing than hostility.

McBride’s strategy also reflects a key insight from the power strategy mix. Integrative power – legitimacy, connection, shared values – is the most overlooked and most important form of power. Kenneth Boulding, who first defined these three categories, argued that integrative power is foundational:

Without some sort of legitimacy, which is an aspect of integrative power, neither threat power nor economic power can be realized to any large degree.

This problem is not unique to the left. The right often frames disagreement as a battle over the soul of the nation. That frame ignores the large number of moderate Americans who may not feel so hot about certain progressive policies (say, DEI initiatives) even if they’re otherwise wary of MAGA.

A simple rule: Strategy follows perception

Coercive power – fighting, escalation, threats – is sometimes the right choice to prevent harm. The risk is that the conflict becomes more entrenched not because the other side is so hostile, but because we assumed they were.

If you misread your audience(s), you will choose the wrong strategy. If you choose the wrong strategy, you will make the conflict harder to resolve. And if that keeps happening, nobody wins – even the side that thinks it’s winning.

Quote of the Week

If you think the only way to talk to somebody you disagree with is to first surrender to them, you don't have a theory of persuasion. You have a theory of insularity and insecurity.

What a surprise to find this post! Please see my 2021 book, "When to Talk and When to Fight: The Strategic Choice Between Dialogue and Resistance" from PM Press.

I like the five styles of conflict resolution in the Thomas-Kilmann instrument and would love to do a live substack event with you to discuss.