Using AI for Conflict Resolution Around the Globe

My Build Peace 2025 trip report from Barcelona - BCB #174

Build Peace is a shockingly global gathering of “conflict nerds” now in its 12th year. One of the organizers, Helena Puig Larrauri, is a friend and co-author, which is how I ended up writing about the very first conference at MIT in 2014. This year, it was just outside Barcelona at the International Catalan Institute for Peace (ICIP).

AI for consensus building in Yemen

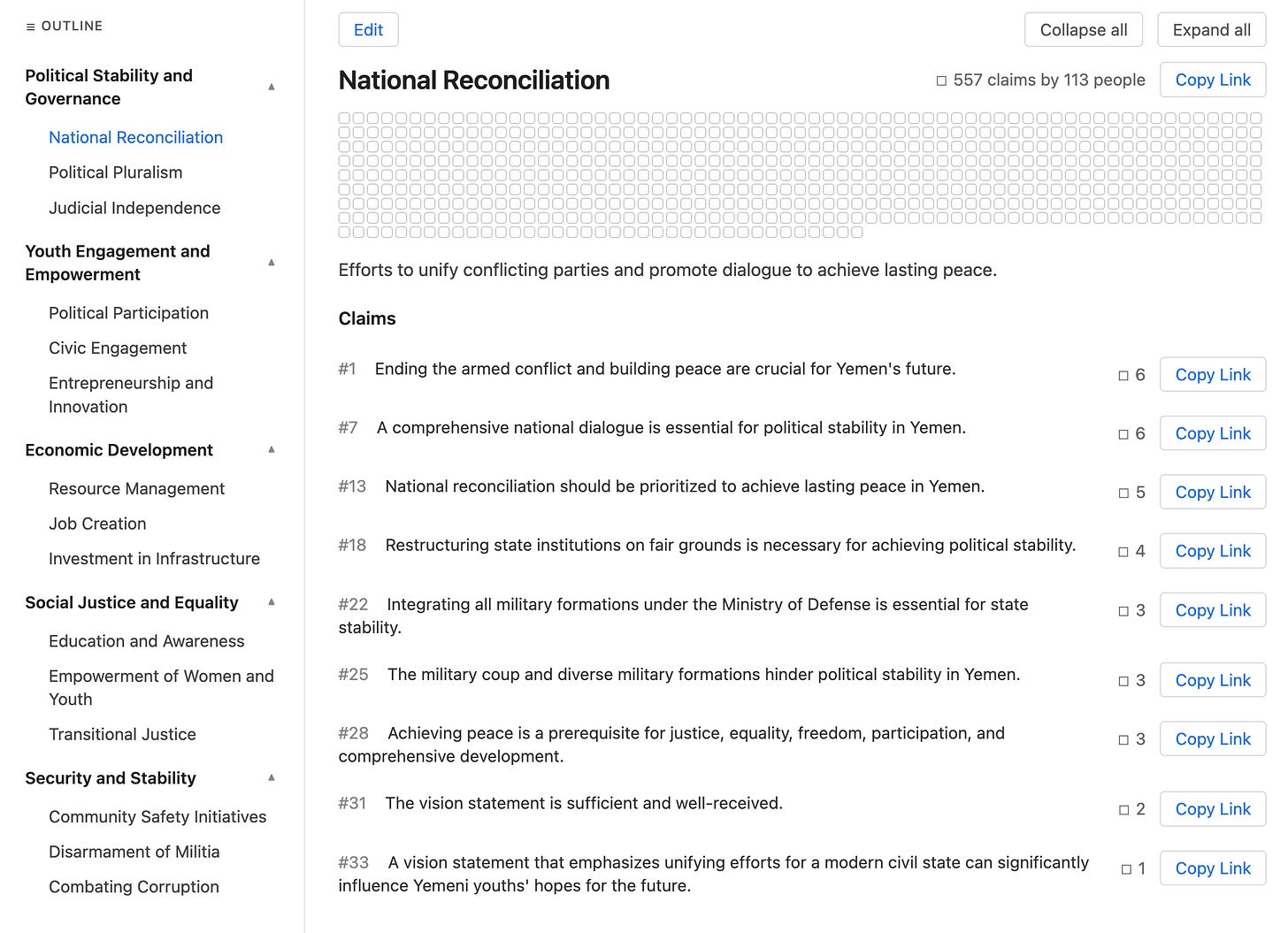

Felix Kufus gave a short talk presenting the use of Talk to the City, a platform which uses LLMs to synthesize diverse public input, to create a vision statement agreed across all seven political parties in Yemen.

This was a unique use of multiple AI technologies. The team, from Finnish peacebuilding organization CMI, deployed Talk to the City over WhatsApp, asking youth from across the country to answer 10 open-ended questions. And they could answer via voice messages which were then automatically transcribed, so people shared very long, very open ended accounts. There was was live monitoring through a dashboard, showing how many responded from which parties.

Talk to the City then synthesized all of this into a report showing six main topics, 18 subtopics, and over 1000 “claims.”

Kufus emphasized the role of trust in this process. “You open a link and give your political views, is this safe?” They were able to succeed because their organization already had connections to stakeholders

“This allowed qualitative analysis on quantitative scale,” he said.

As far as I can determine, this is the first use of LLMs in a deliberative peace process. (Previous work has used Remesh and Polis in Yemen and Libya, but these used collaborative filtering and text clustering algorithms, not LLMs per se.)

Platform polarization footprints in Kenya

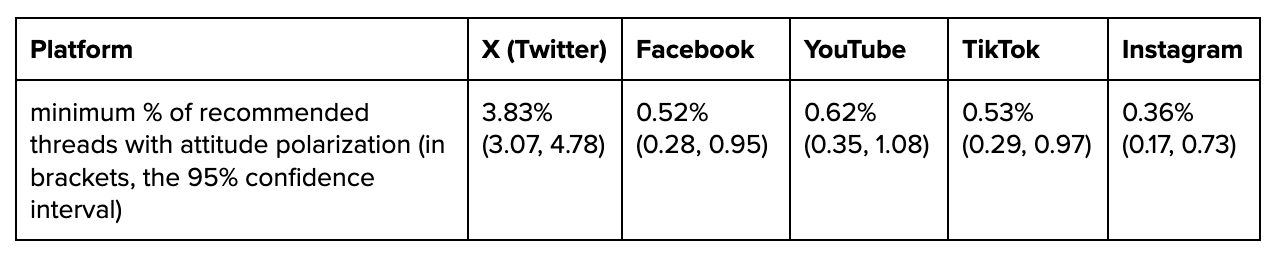

Build Up presented their work measuring the polarization footprint of social media in Kenya. The basic idea is to measure what fraction of people’s feeds is “polarizing” content, which they did on five different platforms.

To do this, they recruited 5,000 Kenyans to install a custom browser extension that, with the participant’s consent, downloaded a snapshot of their feed from these five platforms. They then used an LLM-based Swahili-language classifier to detect polarizing content. (See also the POLAR multingual polarization detection benchmark — not used here but very cool.)

These numbers may not seem like a lot, but put them into context of social media use:

This means that for every hour you spend on X, on average you’re spending a minimum of just over 2 minutes on polarizing content. 55% of Kenyans are spending 3–9 hours on social media per day; if that time were spent on X, then your average Kenyan would spend at least 7 to 21 minutes exposed to polarizing content. Imagine being shouted at for 7 to 21 minutes every day. No wonder we feel angry.

The point of all of this measurement work is to make the polarizing effects of platforms visible. These effects are essentially an unwanted externality of social media, and like all externalities it must be measured before it can be internalized. In this case, the team has proposed a “polarization footprint tax” that would incentivize platforms to have less negative effects.

I have some questions about whether this methodology is truly measuring the right thing, how a tax would work, and so on. You probably have questions too! In my view, the value of this early work is to make the problem visible and start the conversation. Even if the measurement methodology or the proposed policy fix are wrong, now we’re at least talking about the problem.

On the ground in Syria

While technology runs through the heart of the event, I was personally most inspired by the people doing lots and lots of old fashioned mediation. Perhaps this is because I have learned the painful lesson that knowing about good conflict isn’t the same as being able to actually do good conflict.

I attended a workshop led by Ribal Azzin of Olive Branch, a Syrian peacebuilding organization. He brought youth together across all regions, online, to discuss the future of their country. At first his organization approached people individually, then gathered them together in group calls, and eventually all of the participants met in person in Damascus.

Part of their method is a code of conduct for discussion, including what language to use when describing sensitive topics. This was written in consultation with the participants themselves.

Political Correctness: Use terms that do not incite tension and division among partners, as suggested below:

…

Kurdish Forces: Referring to the Syrian Democratic Forces that control areas in northeastern Syria and replacing it with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) or other non-controversial terms.

But that’s just the frame. What’s the content? Azzin started his workshop with an exercise. He put a slide on the screen that said:

Minority rights or Majority identity

He asked people to physically move to one side of the room or the other depending on which side they felt like they were on. Most went to the “minority rights” side.

“Why did you pick the side you went to?” he asked. He got one person from each side to explain their reasoning. “The minority is always threatened in conflict,” said one person. “But look at this room,” said the person on the other side, “in the peacebuilding field no one wants to speak for the majority, and that causes problems.”

Azzin put up the next slide.

Group dignity vs. National stability

Again we split into groups; again one person from each side explained their logic. Then one more slide:

National identity or Ethnic/religious identity

The punchline is that all of these are false choices. When working with Syrian youth, Azzin played a game called “who benefits?”

who benefits when minorities and majorities see each other as threats?

who benefits when dignity and stability are framed as opposite goals?

who benefits when national identity is put against religious or ethnic identity?

“We all inherited this conflict,” Azzin would say to his Syrian participants. “Binary options are a tool manipulators use.”

The challenge for those who want peace is that anyone who rejects this false choice is going to be attacked.

There’s no middle ground, there are no middle voices, because this is conflict. This is the real issue with peacebuilders, because they always want to stay in the middle, but sometimes it’s framed [by others] as, you are stabbing your country or your group in the back.

When you say, “us vs. them, it’s not true,” they hear, “they are a threat to our country, a threat to our existence.” People called me a spy, they called me a lot of bad stuff.

The middle voice is always oppressed.

Azzin’s answer is simple: “Show them how much we are going to lose if we don’t work together.”

I couldn’t help thinking about how these ideas apply to the American situation. I’ve certainly been called bad things in conversations where I’ve tried to convince one side that they should work with the other. Yet, while there are real differences in values that cannot simply be papered over, we are losing so much more than we have to in the way we are fighting.

Very rights-based

I was surrounded by peace nerds talking about inclusion and plurality, but I have to confess, sometimes the event didn’t feel very inclusive or plural. Speakers often talked with the unstated assumption that left-ish politics are obviously correct. At times I felt the uncomfortable dissonance of being around a group of people explicitly talking about cooperation across political differences, with no one who was actually different in attendance.

I talked to others about this, and got some useful perspectives. First, we were seeing in part the politics of our Catalan hosts. ICIP is very classically leftist social justice oriented, if the posters on the walls are any indication. When Build Peace was in Nairobi two years ago, it was a much more conservative vibe in many ways.

Second, while I often saw things in left vs. right terms, that axis doesn’t always translate globally. Others saw things more as the difference between talking about peace and talking about rights. “This was a very rights-based discussion,” said one person. And indeed this was true. We heard about women’s rights, immigrants’ rights, trans rights, and indigenous rights. Nothing wrong with any of those, but they’re all left coded — and advancing rights is related to but not the same thing as advancing peace.

The PeaceTech landscape is expanding

It’s clear we are rapidly entering an area where AI will become an expected part of public deliberation processes. This post is but a small sampling of the space. For more:

You can watch videos of all the plenary sessions here (see the program for a full listing of the talks).

The Council on Tech and Social Cohesion (of which I am a member) recently considered the opportunities and threats of AI for peace.

Project Liberty just posted a list of deliberative tech tools, Platforms that Unite instead of Divide.

If you like this sort of post, see also our Tech for Social Cohesion conference report from 2023.

Quote of the Week

Sometimes in the effort to fix problems with humanity, we think if we can just shut the right people up, these problems are going to go away. And it never, ever works.

Thank you so much for this in-depth coverage, with so many links to useful resources. I've recently been expanding from my scholar-practitioner work in human group facilitation and democratic innovations, https://jabsc.org/index.php/jabsc/article/view/9129/8518 to exploring the landscape of AI, with its many risks and possibilities... https://publications.rifs-potsdam.de/pubman/item/item_6004873. My brief two-sentence summary would be, 1) we need to embrace complex thinking by being aware of BOTH risks and benefits, AND 2) as we do so, we need to continually question the discourses of "inevitability" to expand our sense of possibility...

Connect first, correct second.