At the Designing Tech for Social Cohesion conference, peacebuilders and technologists envision a less polarized future

On the last weekend of February, Technologists and peacebuilders sipped their coffee from sustainably made wheat-based mugs at the first-ever Designing Tech for Social Cohesion conference in San Francisco. The mugs were printed with a word cloud: collaboration, transforming conflict, building bridges, and closing perception gaps. In the largest font: “design for social cohesion.”

The opening session described “social cohesion” as the basis of everything we want to do in society. It’s gaining “trust between people (horizontal trust), trust of institutions (vertical trust), and agency for citizens,” explained Shamil Idriss, CEO of the international peacebuilding organization Search for Common Ground.

There were two main ideas at the conference: existing platforms should be re-designed for social cohesion, and peacebuilders can use various types of tech for the work they already do. You can watch the live-stream videos here, and of course, we live-tweeted it under the hashtag #tech4cohesion. In this post, we’ll cover what we thought were the most interesting talks and their takeaways.

Setting the Stage for Designing Tech for Social Cohesion

The conference set the stage with definitions and objectives of the conference from Tristan Harris, co-founder and executive director of the Center for Humane Technology, Shamil Idriss, CEO of Search for Common Ground, and Lisa Schirch, senior professor of the Practice of Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Much like public health professionals, technologists and peacebuilders can moderate content and design “healthier” platforms, said Schirch. For example, design influences users’ experiences through social media incentives. Most platforms currently optimize for engagement in some way, and conflict-y or outrage-inducing material is more engaging. (We’ve previously covered research on how social media might also be driving polarization through another effect, partisan sorting.) Is there some way we could instead incentivize users for social good?

The panelists discussed technology currently being used for peacebuilding, like The Perception Gap, a quiz to help people identify their biases and misperceptions, and the Angry Uncle Chatbot which gives users tips and tricks on how to avoid turning discussions into debates. But there’s more that can be done. Peacebuilders have been working on conflict for generations. Therefore, we can and should take ideas from the field of conflict resolution to inform depolarization efforts, and the design of tech platforms.

Tech for Intergroup Dialog

The talk is split into two videos. Watch the first video here and the second video here.

The talk focused on examples and best practices for having different ideological groups communicate with each other. Moderator Lena Schlachmuijlder, VP at Search for Common Ground, lead the discussion with panelists, Lisa Conn, co-founder and COO of Gatheround, Arik Segal, founder of Conntix, Waidehi Gokhale, CEO of Soliya, and Lucas Welch, founder of Slow Talk.

Gatheround is an online team-building tool. While this may seem out of place at a conference on social cohesion, Conn is a former Facebook polarization researcher, and pointed out that the workplace is where we’re most likely to have conversations across lines of identity.

Soliya is a more traditional peacebuilding program. It facilitates small online group discussions that meet repeatedly over weeks or months. Gokhale explained that these conversations work only if you are willing to look at your biases and practice deep listening. She also pointed out the divide between social media intention and impact. While platforms such as Facebook were intended to encourage togetherness, in reality, it’s become a tool to further isolate from others. “We have to change,” she said.

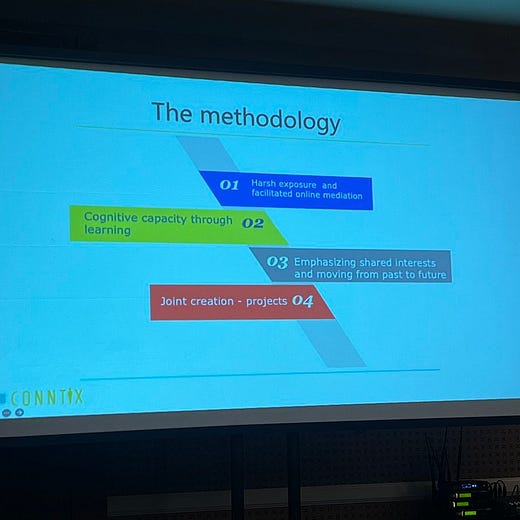

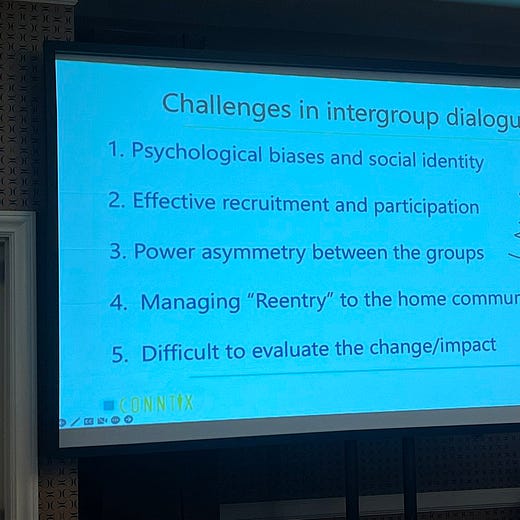

Segal discussed how to have a successful depolarizing intergroup dialog, in the Israel and Palestine context. You cannot simply pretend existing divides don’t exist; “first you have to fight,” he said. After that comes moving away from past frustrations to sharing common interests and collaborating on projects. The method is a Facebook group with a mediator, sustained over weeks or months.

Welch used the metaphors of aspirin and oxytocin to describe his case for intergroup dialogue. He used aspirin to describe the need for pain relief when dealing with conflict. In other words, there is a demand for social platforms to help users feel less isolated and depressed when using them. But there’s another need, which he analogized to oxytocin: “People want to belong,” he said.

Metrics for Polarization and Social Cohesion

The talk is split into two videos. Watch the first video here and the second video here.

Moderated by BCB’s Jonathan Stay, panelists included: Ravi Iyer, managing director of Psychology of Technology Institute at USC Marshall’s Neely Center, Julia Kamin, director of research and evaluation at Civic Health Project, Emily Saltz UX researcher at Jigsaw, Adrienne Brooks, senior advisor at Mercy Corps, and Aviv Ovadya, an affiliate at Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University.

Stray described three different ways metrics are used in peacebuilding or social cohesion efforts: measuring outcomes from traditional programs such as inter-group dialogue workshops, measuring polarization indicators on platforms, and using metrics to directly drive content ranking. An example of the third type of metric is bridging-based ranking, where a platform tries to promote content that appeals to a politically diverse audience.

Iyer argued that we should not regulate speech, but platform design. For this to work, panelists said researchers need access to platform data sets to better understand the way users interact online and to identify user needs. For example, it is not easy to determine, from the outside, whether and how the design of these platforms are increasing polarization. Brooks said tech companies have the data, but peacebuilders have an eye for the context. “Together we need to identify, align, and be consistent about the frameworks we are using to identify the problem,” she said.

Yet the right design is far from clear. When asked what metrics we should use — instead of engagement — to determine what people see, panelists hesitated to give answers. Suggestions included measuring civic alienation, trust, and whether the user connected meaningfully with someone else in the last 30 minutes.

Insights, Inspirations, Ideas

Watch the video here.

For the final discussion, “Insights, Inspiration, Ideas,” Shamil Idriss, CEO of Search for Common Ground moderated a panel with Tristan Harris of the Center for Humane Technology, Sahar Massachi, of the Integrity Institute, Deepanjalie Abeywardana at Verité Research, and Daanish Masood at the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) Innovation Cell.

There has never been as much momentum to operationalize peacebuilding into software. Yet Masood pointed out, “We operate in an environment where there are no commercial reasons for this to be.”

Harris said, “You’re on a very long journey. For the next five to seven years you’re just sounding the alarm before you see change.”

This conference imagined a world where users feel more connected from their social media feeds, not isolated or depressed. That starts with design that informs users how to interact with each other and incentivizes constructive conflict rather than destructive conflict. Or as Iyer put it in the metrics panel, it’s ok — even necessary — for people to disagree, but we want to get rid of “cheap conflict.”

There are at least two types of trust deficit in societies, other than distrust between ideological groups. When I expect a random big tech company to cheat me, casually harm me, etc., the problem probably isn't that they are in a different ideological group from me, unless you consider properly socialized MBAs and corporate executives to be a separate ideological group from non-MBAs. And if I and everyone I know expect most random people in the street to be selfish bastards who cheat, steal etc. whenever they can get away with it, I probably come from a low trust society.

This is where I thought the discussion would be going, rather than better communication between ideological groups.