Surprising Validators in Unlikely Places

Alt-right commentators and progressive undergrads can — and should — critique their own side — BCB #148

Earlier this month, right-wing political commentator Richard Hanania published a searing indictment of the Trump administration’s decision to ship Venezuelan migrants to El Salvador, and of this administration’s “moral nihilism” more generally. The post is striking less for its content than for who it is coming from.

Hanania first made a name for himself in Red circles; a 2023 Huffington Post story called him “a formative voice during the rise of the racist “‘alt-right.’” In fact, his writing directly informed an executive order banning affirmative action that Trump issued on his first day back in office (something he cited in another critique of Trump he recently published in The Economist).

All this to say, it’s surprising to see a careful yet damning deconstruction of the Trump administration’s immigration policy bearing Hanania’s byline. Hanania has become a a surprising validator, a phenomenon we’ve written about before wherein people critiquing their own side are more likely to be heard than those trying to speak to their opponents.

If you weren’t looking at the byline, you might think Hanania’s piece was written by someone who is deep Blue:

Over the first few months, it’s become clear on several issues that one of the things that makes the Trump movement so difficult to criticize is that it engages in multidimensional lying. They will lie about the “problem” they are trying to solve. They will lie about the effects of their policies. They will lie about the justification for that policy, and its legal basis. They will then pick examples of things they have done to solve the problem that will also be lies. They will lie about how the policy is working, and even what the courts have been saying about their policy. These aren’t misrepresentations that leave out context. We are talking about bald-faced lies by any definition, any one of which would be a scandal in most other administrations. It’s difficult to prove in most cases whether any particular official knows that he is lying, but the inference can often be made, and whether someone is a liar or a true-believing cultist in any particular instance, the effects are usually the same.

This is a pretty striking turn from someone who defended his decision to vote for Trump in the run-up to the 2024 election. It’s only in recent weeks that Hanania has changed his tune and says he regrets his choice. Last week, he even took to X asking whether anyone could help remove the “right-wing commentator” label from his Wikipedia page. (“MAGA is the main dividing line in politics and I think MAGA needs to be defeated, so it’s inaccurate.”)

That line seems unlikely to do much for people on the left who remember when Hanania was publishing white supremacist takes under a pseudonym. But what about people on the right? Most of them stand by their choice to vote for Trump. In theory, the virtue of surprising validators is that they may be more effective at getting through to people and changing, or at least complicating, their beliefs. And if the comments beneath Hanania’s post are any indication, Red readers are engaging with his arguments, whether or not they agree with them.

Bridge-building finds a home on a stereotypically monolithic campus

The University of California, Berkeley has long held the reputation of being a place for progressive activists. It was home to 1964’s Free Speech Movement, and that spirit persists today. But that doesn’t mean the university is monolithic. Recently, an official newsletter highlighted an array of efforts underway to foster bridge-building and expand the nature of political dialogue on campus.

These include a new campus chapter of the Heterodox Academy, a national organization devoted to promoting “viewpoint diversity” in higher education. (Regardless of what one may think of “viewpoint diversity” as a goal, it’s very clear that academia is not diverse in this way.) This group is working with the Berkeley Initiative for Free Inquiry, which formed from informal talks and meetings a few years ago with the goal of improving “the climate for free inquiry through research, teaching and service,” and the more established Berkeley Liberty Initiative, which brings a range of political voices to speak on campus. Together, these groups hope to “counteract toxic polarization by expanding the space where liberals, moderates and conservatives can find constructive engagement.”

Their work builds on Berkeley’s mounting reputation as a “national center of innovation in ‘bridging.’” Other recent efforts in this vein on campus include a new course for undergraduates, “Openness to Opposing Views,” which aims to teach students the “(nearly) lost art of disagreement.”

Given the school’s reputation, you might not expect its affiliates to make ideologically diverse conversation a priority – another example of “surprising validators”. The fact that these initiatives are happening at Berkeley gives them additional weight, and makes a statement about what (at least some) students today want.

As one member of the school’s Heterodox Academy chapter put it,

Ultimately, I came to Berkeley to be intellectually challenged, inside and outside of the lab. We need to be willing to disagree with each other openly, but to do so civilly. I want others to be intellectually charitable to me, and I want to do the same to them.

Responding to arguments against depolarization

There are many reasons why people tend to push back against arguments in favor of conflict resolution or deescalation, especially when the conflict at hand feels existential and dire. Polarization researcher Zachary Elwood is all too familiar with this stance—and he argues that it’s important not to give into thinking this way.

Elwood lists some of the most common objections he hears—things like “Isn’t it normal for us to disagree?” He’s written an explanation of why polarization is, in fact, a problem.

Or: “Depolarization and bridge-building work is just ‘both-sides-ism’; you’re helping the bad guys.” Here’s how he responds to this:

Many people view us as “helping the bad guys” — or even as just “the bad guys.” This is a dynamic anyone involved in conflict resolution will recognize. We get it; fears and emotions are high. When you perceive yourself and the things you care about under threat, a focus on seemingly trivial things on “your side” can seem clueless — an insult to your intelligence. You might start to wonder if we have a hidden agenda.

…

Let’s imagine we focused only on examining the polarizing behaviors of one political group. If we did that, we’d no longer be persuasive to people in that group. They’d see us as entirely partisan — and they’d be right. We’d simply be preaching to the choir. We’d be another cog in the engine of polarization.

For each of these common arguments against bridge-building, he links relevant articles he has written for the Builders Movement over the last year and a half. Perhaps you, too, could be a surprising validator and help people on your side see the potential problems in their own way of thinking.

Quote of the Week

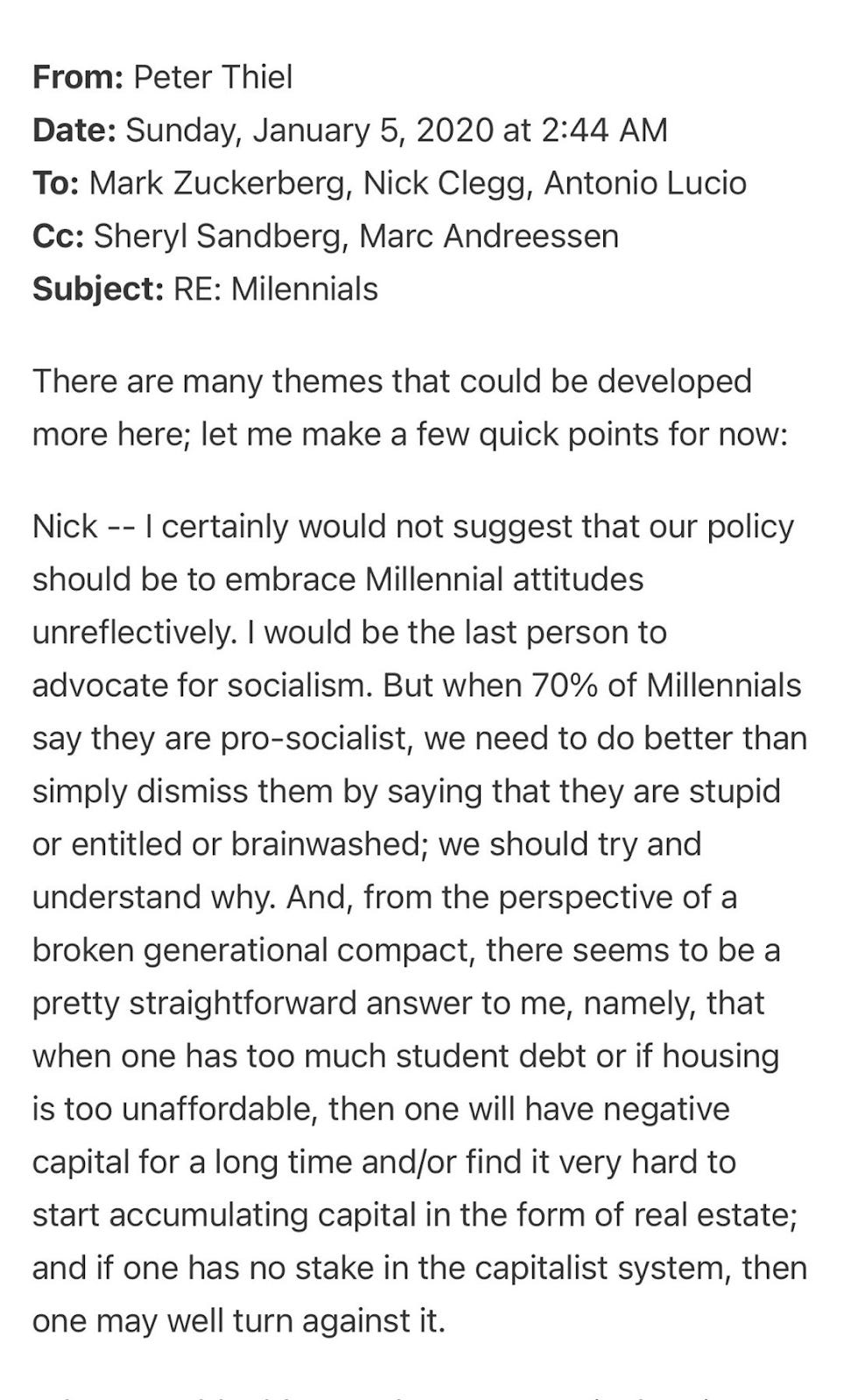

Peter Thiel as an anti-capitalist surprising validator:

— via Lee Edwards

Hanania's case may not really be that of a surprising validator because he was being substantially rejected by the right (all the recent "Elite Human Capital" taunting), but it's still an interesting word to have and an interesting application. How does "switching sides when rejected" play into polarization dynamics generally?