Should Abortion Laws Be the Same Everywhere? – BCB #112

How each party is handling abortion underscores a perennial tension between two deeply American principles: universal rights and self-determination.

In November, voters will choose between a universal right to abortion or the devolution of abortion rights for states to self determine. It might be the deciding issue of the election.

The Trump campaign is eager to push the political hot potato down the ballot. The Republican party has pragmatically removed its long standing commitment to a “Right to Life” constitutional amendment from its 2024 platform, reverting to the “back to the states” line of reasoning that has historically played well with Red voters who value local decision making.

Meanwhile, the Democratic campaign has committed to making abortion up to the point established by Roe (fetal viability, usually around 24 weeks) a universal right in federal law.

The contrast in these approaches exemplifies the perennial tension between two equally American principles: universal rights and self-determination. The values underpinning Red’s preference for community self-determination are particularist: loyalty to and care for the community or in-group. Blue universalist values speak to a moral code that emphasizes equality and impartiality.

Universal rights and self-determination are both quintessentially American concepts, the products of long and deeply considered intellectual traditions. But they don't play nicely together. The US’s nested governance structure is designed to manage the tension, but it can only do so successfully if those who hold each ideal recognize that the values of the other are valid, and held in good faith.

Reconciling self-determination with majority rule

Traditionally, universalist politics—the idea that there is some set of rights or responsibilities that applies to everyone—is associated with left-ish politics. Conversely, particularist politics—the idea that rights and responsibilities are affected by circumstances—is associated with right-ish politics.

This division still plays out this way in today’s America. Think “states rights” (a stereotypically Red value) versus “human rights” (often invoked in Blue language).

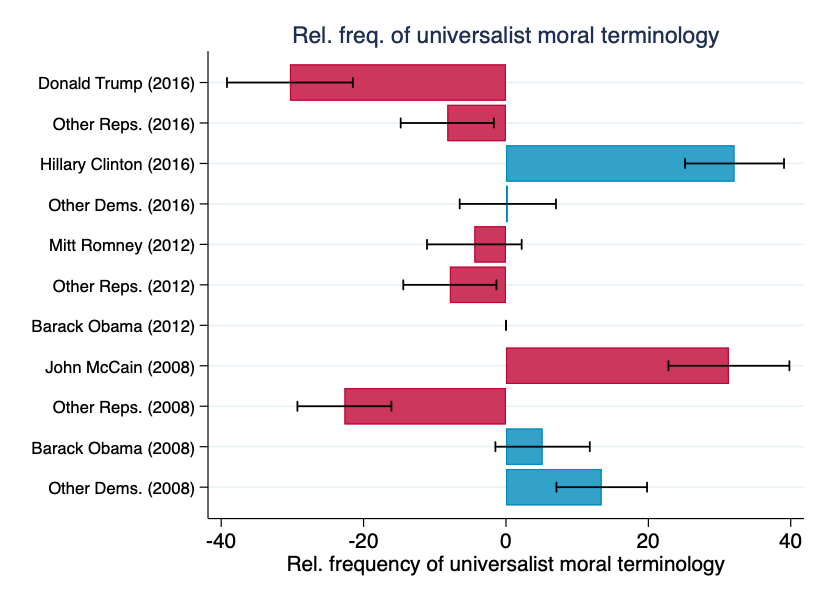

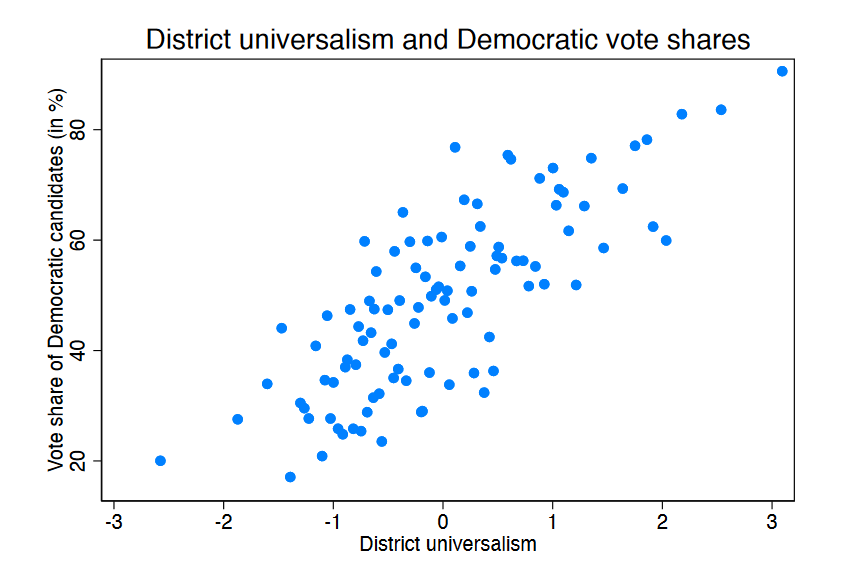

It’s not just anecdotal. Blue politicians speak in universalist terms more often.

A 2023 study examined behavioral data from a charitable giving platform, looking at how similar the giver was to the recipient, geographically and socially. This provided a measure of universalist values, which turned out to correlate strongly with voting patterns. The link between values and political behavior was stronger than all other traditional predictors of Red/Blue affiliation, like income or education. The authors concluded: “a considerable fraction of the geographic political divide may result from disagreement over universalist versus particularist moral ideals.”

Yet there are plenty of cases where Blue thought invokes particularist ideas and Red politics supports universals.

Self-determination as a principle might be most closely associated with nationalist movements, but it’s also a key feature of anarchist political thought which envisions as-local-as-possible governance. Red wants localized abortion law and parental control of local school boards, while Blue supports sanctuary cities and California’s right to stringent environmental regulation.

Unfortunately, self-determination as a principle doesn’t scale especially well. Once we go from an individual to a group, whether that’s a family, a neighborhood, a city, or a state, fragmentation inevitably occurs, and some gnarly questions arise. What’s the threshold of consensus needed to create a rule or a right that applies to everyone in the group? What’s the threshold for a minority or subgroup to claim the same right to self-determination?

When the fundamental premise of democracy is a formal process to ensure majority rule, large minority groups—who may be more consistent in their beliefs and values than the population as a whole—often invoke self-determination in their opposition to policies that take decisions affecting their communities out of their hands, whether on healthcare, education, or public safety.

The tension between the universal and the particular also underpins the delicate balancing act of federalism. We see it play out every day in the relationship between national and local politics. Many of our arguments end up being about whether a particular decision should apply to everyone, or just a specific community.

Finding consensus

Now that Roe's universal protection for abortion rights is gone, campaigns are underway to create state-level laws and regulations, both pro- and anti-abortion. The legal foundation created by resistance to the Affordable Care Act’s insurance mandate is also applicable to abortion. “Health care freedom” bills enacted to preserve freedom of choice in medical care at the state level have been used to challenge restrictive abortion legislation in states like Ohio. Elsewhere, ballot initiatives are putting abortion directly in front of voters.

In the reddest states, this means some abortion rights advocates are designing compromises to get abortion on November’s ballot in ways that conservative communities may be able to accept—taking a self-determination approach to leverage the surprising amount of consensus that exists once the issue is taken out of its universalizing framework.

Advocates for universal abortion rights say that the Democrats’ proposals won't go far enough, because they would still allow states to regulate late-term abortion and impose other restrictions. In deep Red states like Arkansas and South Dakota, where citizens have petitioned to get limited abortion rights onto the ballot in November, some progressive organizations have chosen not to fund campaigns that would restore fewer rights than those previously guaranteed by Roe. As Beth Huang of the Tides Foundation, a progressive fund that has given generously to abortion ballot measure campaigns in Florida, Colorado, and Nevada, said:

Our motto is, “No steps backwards.” Roe is the floor, and we are prioritizing measures that reestablish the floor. We don’t want to support policies that enable backsliding.

But in Arkansas and South Dakota, where trigger laws banning all abortions except to save the life of the mother came into effect after Dobbs, these sorts of ballot initiatives must be acceptable to deeply conservative voters to have a hope of passing. In Arkansas, where a minority of voters believe that abortion should be legal in “all or most” cases, the campaign has been crafted to appeal to the values of limited government and the ballot measure offers conservatives a compromise on time limits—up to 18 weeks, instead of 24 as is common for ballot initiatives seeking to restore Roe.

Devolution of abortion rights to the state and level feels very unsatisfying to people who are invested in the ideal of universal rights, even as state-by-state access expands to better represent the view held by most Americans that abortion should be legal in some, if not all, circumstances.

The resulting plurality of laws may resemble a patchwork, but it also represents a degree of self-determination in the policy process. On an issue that struggles to attract Red support at the federal level, reaffirming a sense of self-determination in creating and voting on state-specific regulation might help to break the long standing all-or-nothing deadlock over universal rights.

Quote of the Week

Any system of thought must have a place for both particular and universal.

I thought that the point of abortion rights *was* self-determination. Going down from federal-level rights to state-level rights or restrictions does localize the issue somewhat, but it is far from giving local communities the right to decide for themselves. If a local, small community wants to ban abortion for their members, that can honor the members’ right to self-determination as the community can get to know the members’ individual needs and concerns in a way that no state or country or even county can. Personally, though I would describe myself as leftist, I am against abortion for myself. I just think it would pain me a lot to let go of the potential of life that a fetus represents. I think a lot of abortion rights advocacy that focuses on empowering pregnant people to choose abortion can fail to acknowledge how difficult it can be to decide to let go of a fetus, and also how valid it is, from an individual standpoint, to be even staunchly against that option. But I do honor self-determination, and I would never tell someone not to have an abortion based on my own opinion.

I'm confused.

If 51% of elected politicians in some jurisdiction agree that women who will die of their pregnancies should not be allowed to abort the fetus to save their lives, how is that *self* determination for the women involved? It seems to me that this is "self" determination in much the same way that the right to own slaves is "freedom".