Campus Deplatforming is on the Rise. Is that bad? – BCB #95

An undeniable uptick in campus deplatforming

Since the events of October 7, the question of free speech at American universities has once again been making headlines. Some have argued that campuses, once home to the open exchange of different ideas, have strayed from their stated purpose in the name of trying to ensure that students feel comfortable. But is there any data to back this up?

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) has been tracking campus speaker protests and deplatforming for some years in their Campus Deplatforming Database. The define “deplatforming” to include disinviting speakers with controversial or pointed political views, successfully removing displays of artwork, or canceling screenings. Founder Greg Lukianoff recently took a look back at decades of data to argue that “a significant portion of college students have become more hostile toward free speech than previous generations.”

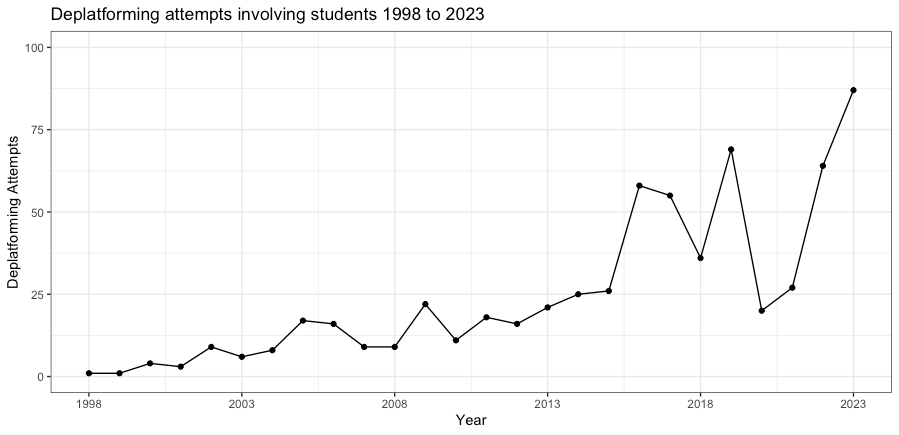

The average number of deplatforming attempts by students was six times higher in 2014-2024 than it was between 1998 and 2013, and 2024 is on track to be another record-breaking year. The success rate of these attempts is also up, from 36% to 44%.

Event disruptions are also on the rise. The average number of substantial event disruptions in the past decade—where speakers were interrupted for a considerable period or completely shouted down—is five times what it was between 1998 and 2013.

It’s worth noting that FIRE has a strong incentive to collect this data—campus speech issues are the organization’s bread and butter. And while it bills itself as being nonpartisan, others have pointed out that the nonprofit has received funding from a variety of Red-leaning groups and individuals. But as often happens with highly charged issues, only partisans are willing to go through the trouble of doing detailed research. Blue often denies there has been any change here.

Who is doing this?

Deplatforming is a bipartisan game. It used to be more popular on the Red side, largely driven by anti-abortion and anti-gay activism. Over the last decade, it’s more often been Blue who tries to shut down speakers.

This flip follows a broader shift in society. “Free speech” used to be strongly associated with the left; the 1960s Free Speech Movement originated with leftists at Berkeley. Until recently, journalists were stereotypically the champions of free speech. Post-2016, they’ve often taken to criticizing the idea. The extremely online Blue have even taken to mocking it as “freeze peach.”

Some time in the last decade, “free speech” flipped from Blue-coded to Red-coded.

But is this bad?

As we pointed out in a recent issue, the most politically engaged people are frequently the most partisan. Hence, this increase in deplatforming attempts and event disruptions could just be a consequence of student bodies becoming more politically active. If we think engaged citizens are good for democracy, then this increase in political activity is a good thing. Everyone should fight for their values.

But the premise of this publication is that we also need to fight better. Not all political tactics are equally productive, and this is especially true when it comes to shutting down speech (see: does censorship even work?). Further, preventing people from speaking their views is antithetical to the mission of a university.

The counter-argument—from the Blue side, since they’ve been more into deplatforming in the last decade—is that some speech is actually bad for free speech, since it chills others from speaking. This argument is most closely associated with the DEI movement, and they’ve got a point that not everyone experiences their speech rights in the same way. If inclusion and freedom of speech aren’t actually at odds with one another, there’s at least some careful reconciliation required:

the Knight Foundation’s report about college students and free expression shows that on campus, only 5% of Black students believe that the First Amendment protects them “a great deal,” compared with 43% of white students. The stereotype of self-censorship imagines white students fearing punishment for unpopular views, but obviously there’s something more going on here.

Still, there is often something draconian about campus deplatforming. Consider what happened after a Stanford Law School professor apologized to a conservative judge who was prevented from speaking by disruptive students:

When Martinez’s class adjourned on Monday, the protesters, dressed in black and wearing face masks that read "counter-speech is free speech," stared silently at Martinez as she exited her first-year constitutional law class... The student protesters formed a human corridor from Martinez’s classroom to the building’s exit… The few [students] who didn’t join the protesters received the same stare down as their professor as they hurried through the makeshift walk of shame.

In response, Martinez pointed out that this sort of thing is at odds with the very idea of a law school:

Some students might feel that some points should not be up for argument and therefore that they should not bear the responsibility of arguing them (or even hearing arguments about them), but however appealing that position might be in some other context, it is incompatible with the training that must be delivered in a law school. Law students are entering a profession in which their job is to make arguments on behalf of clients whose very lives may depend on their professional skill.

Whatever your interpretation of what is happening, the data FIRE has collected shows that there really has been a generational change in how students respond to their political adversaries.

I feel cranky this morning, so I'll make two points related primarily by crankiness.

1) Restricting discussion of de-platforming to campus events makes it look like a predominantly blue activity. Censoring books in schools and public libraries doesn't happen on college campuses; neither those defunding public libraries and mandating that certain ideas must not be taught in public schools - or perhaps in any K12 schools at all; I haven't checked the details of all the legislation and proposed legislation in this area.

2) If we decide that attempting to restrict free speech on partisan grounds is basically a good thing, being a sign that the people involved are politically engaged, should we also decide that attempting to beat up or assassinate one's political opponents is a good thing - for essentially the same reason? If not, why not?

Yes, I'm something of a free speech absolutist. I'd prefer a lot less public lying, but can't imagine a good way of enforcing honesty without in practice merely enforcing orthodoxy. I draw the line at inciting violence and the traditional yelling "Fire!" falsely in a crowded theater.