But What Do We Teach the Children?

Education in polarized times: what's happening now, what we can do next - BCB #175

In any conflict, there will be a fight over the politics of the next generation. Aside from the recent struggle over universities, there have been deep arguments over primary school curricula and even the books in school libraries. How then should a divided country decide what to teach?

I was surprised to discover that most other countries have already found a way to address these tensions, as Ashely Rogers Berner writes:

[T]hese governments fund a wide variety of schools (religious, secular, pedagogical) but also expect all of them to impart shared knowledge in the major subjects. Nor are pluralistic systems rare; quite the opposite. A full 171 out of the 204 countries UNESCO recently surveyed partner with non-state actors to deliver public education. This is news to most Americans, as is the fact that several key human rights instruments endorse the rights of cultural minorities to educate their children according to their families’ values.

What does this look like on the ground? The Netherlands funds 36 kinds of schools (e.g., Montessori, Jewish, secular) on equal footing. Australia’s federal government is the top funder of tuition to private schools, many of whose students come from the lowest economic quartile of the country. Sweden and Poland let funding follow students to their school of choice. Nations as different as Colombia and Nigeria include both state and non-state providers in their education systems. The list goes on and on because most countries have plural school systems

These systems combine two crucial ideas. First, school choice for parents, but funded by the government. This is similar to the idea of school voucher programs, long discussed in the US, a version of which is set to begin in 2027. Second, a core curriculum that all students must be taught, regardless of the school’s overall orientation.

Furthermore, the most academically successful plural systems also require critical common content to be shared across all these different types of schools. Students take subject-specific exams every few years that, unlike the skills-based assessments our states administer, actually require mastery of core knowledge. … The Netherlands even funds creationist schools, but kids in creationist schools have to demonstrate competent knowledge of evolutionary theory

This approach offers a way to thread the everlasting tension between local self-determination and national standards. Educational pluralism may be radical by current standards, but it fits right in with the core American values of liberty and tolerance.

How to do pluralism in the classroom

Earlier this year the journal Democracy & Education published a special issue on polarization, including three studies that grapple with how to teach charged subjects in high school.

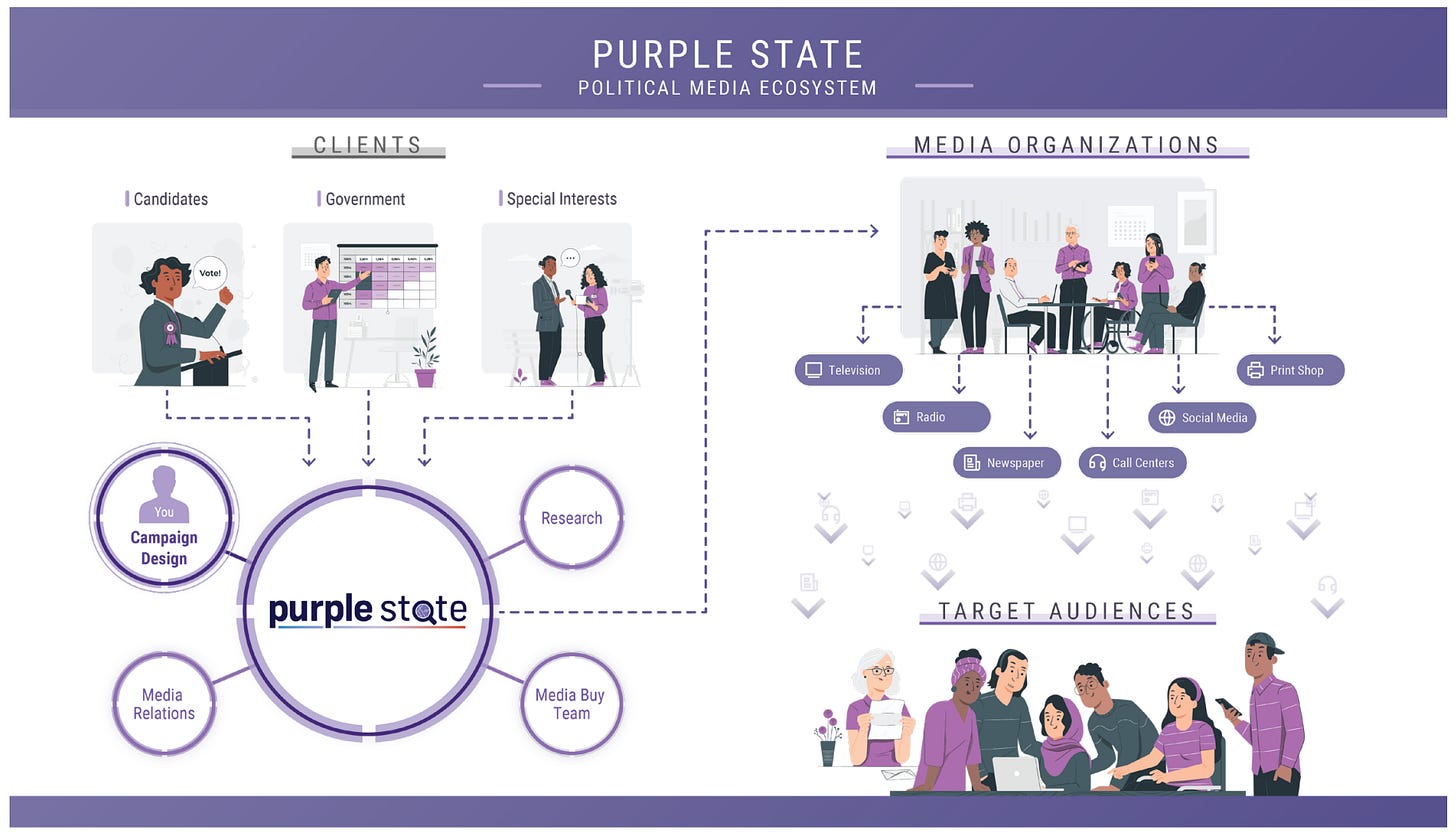

Role playing for learning: PurpleState is a game where students role-play as interns at a political communications firm, designing media campaigns on gun control, climate, and police reform from research briefs and real polling data. Focus groups found students transferred skills to real life: questioning the aims of political ads and seeking out multiple perspectives.

Inter-school dialogues: students from politically and demographically different schools 150 miles apart discussed election issues on a video platform. The experience helped students recognize they were in political bubbles and motivated them to engage across difference.

Debate vs. Discussion: a comparison of “deliberation” vs. “debate” formats among high schoolers. Deliberation produced more comfort (87% felt respected) and less disagreement, while debate was less comfortable (74%) and more disagreement was voiced, but students also said they were exposed to more new ideas. Students with personal stakes (LGBTQ students on the Equality Act, hurricane survivors on climate) mostly reported positive experiences.

Is or isn’t Critical Race Theory taught in school?

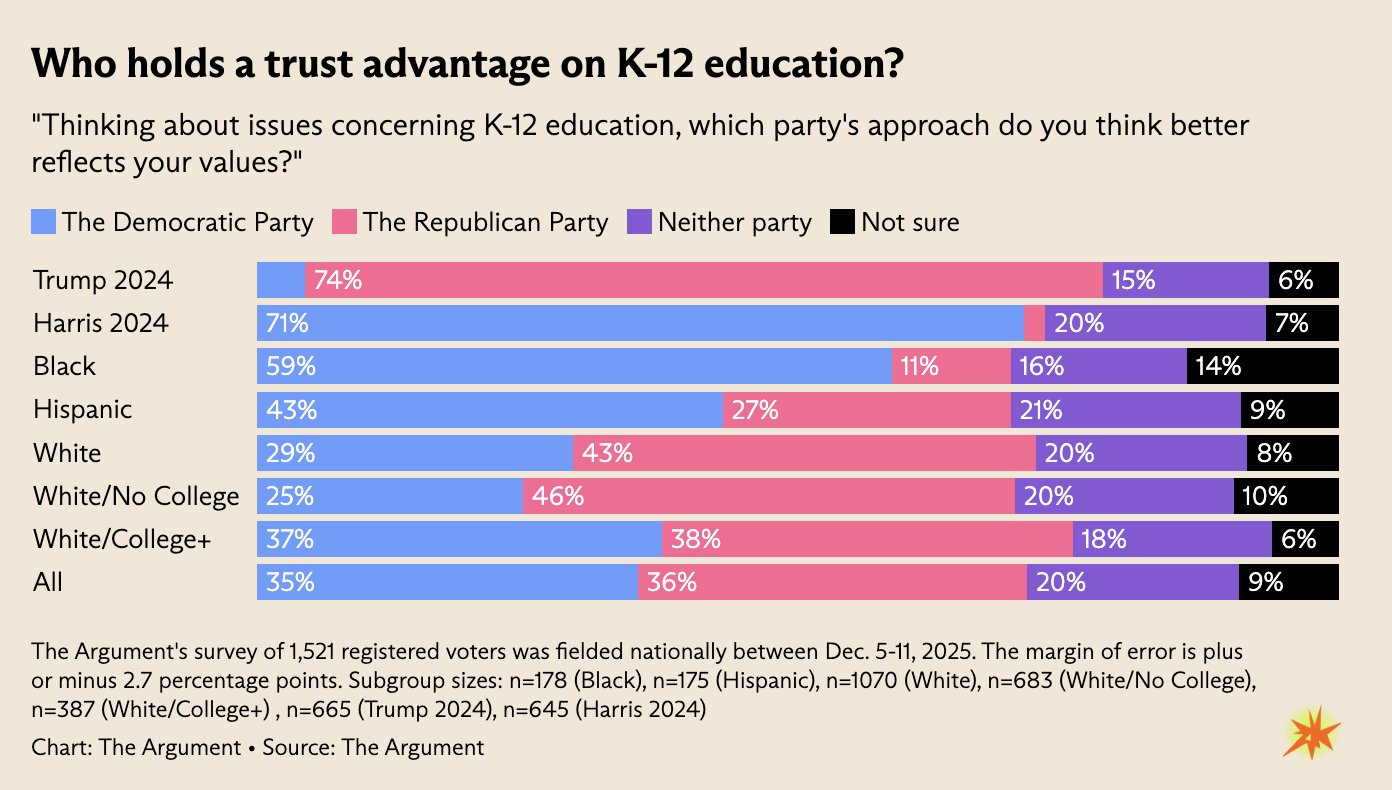

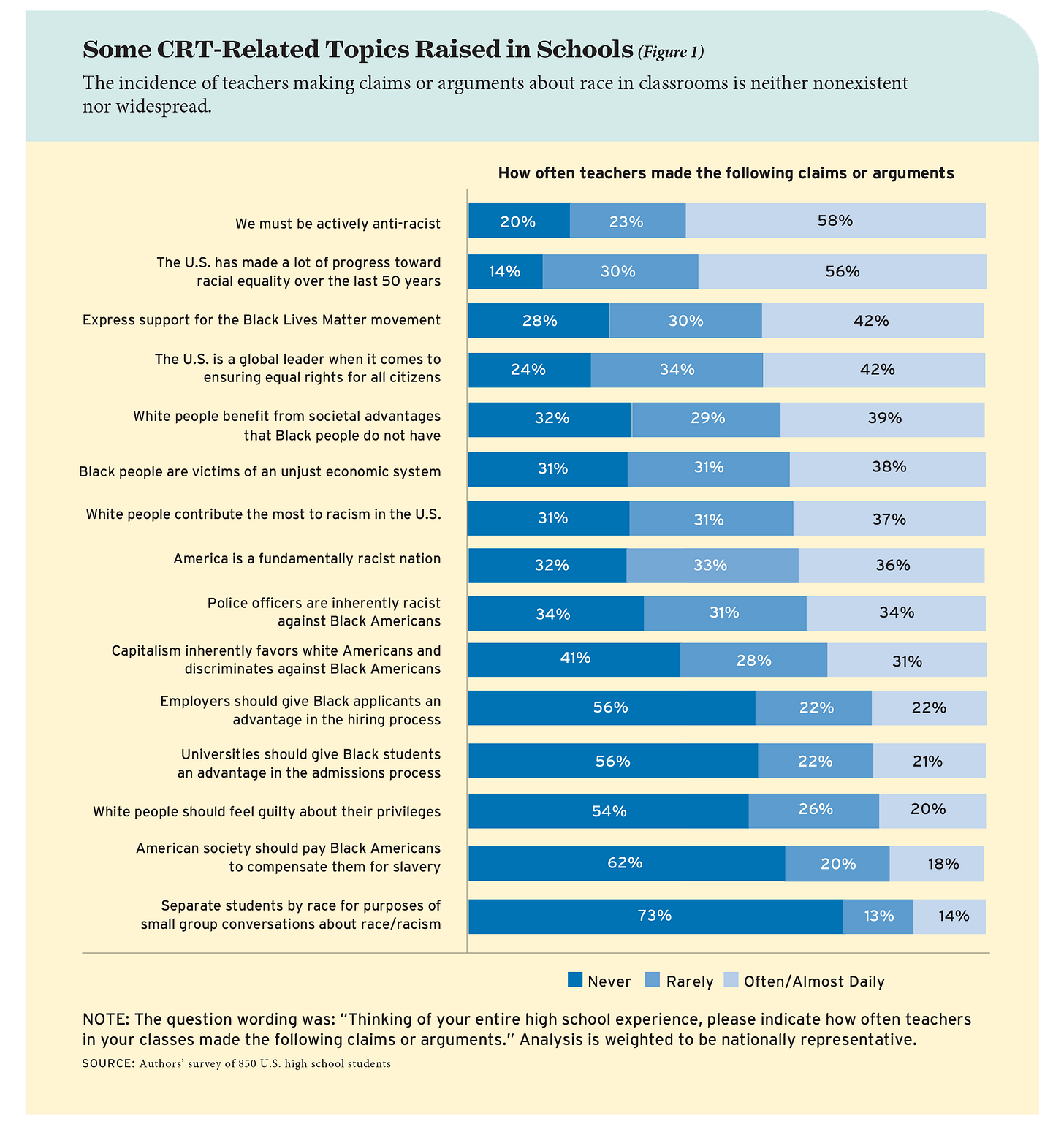

Like all heated political battles, the big public argument over education is often light on facts. It’s therefore refreshing to find work that asks a very basic question: what kinds of politics are American high school students being exposed to today? Well, you could do a survey and find out:

The authors of Bridging the Divide over Critical Race Theory in America’s Classrooms also asked high school students questions about their teachers’ use of various bit of language, including both “Black Lives Matter” and “All Lives Matter.” As above, there’s some of everything, but it’s not always easy to distinguish between discussion and indoctrination.

We would expect, or at least hope, that good-faith conversations in healthy classroom environments would address contemporary debates and present multiple perspectives. And indeed, students report overall that their teachers show an appreciation for viewpoint diversity. Seventy-six percent of students say teachers never or rarely make them feel uncomfortable to share opinions that differ from their teachers’, while 54 percent say their teachers make them feel comfortable to share differing views often or daily. At the same time, 18 percent report their teachers have made disparaging remarks about conservatives or Republicans, and 19 percent say their teachers have made disparaging remarks about liberals or Democrats.

So are our children being indoctrinated with Blue (or Red) ideology?

Overall, one thing that seems clear from our data is that, in the public debate about CRT in education, people on opposing sides are largely talking past each other. Those who think CRT-related instruction is nonexistent should know that it isn’t. Those who think it’s an epidemic should be aware that this isn’t true either. And those who are concerned about indoctrination in education should know that most youth report forming their political beliefs from sources outside of the classroom.

Image of the Week