Anti-Woke and Back Again

Also, trust beats misinformation and gender equity without backlash — BCB #142

Years before arguments about “wokeness” became national politics, writer Katherine Brodsky was an outspoken critic of the obsessive language policing and ideological demands of the 2010s “social justice warrior.” But in a recent Substack post, she points out that “anti-woke” politics, long critical of these illiberal tendencies, has evolved into… a version of the same thing.

How did this happen? The problem, she writes, is that the notion of “anti-woke”

was grounded in resentment rather than hope. Grievances more than solutions. What started as a passion that spurred them to challenge authoritarianism gradually eroded their capacity for empathy and dialogue. The perpetual conflict and state of ‘fight or flight’ broke them in a way, transforming them into a caricature of themselves. The discourse imprisoned them rather than freeing them.

In short, constant fighting warps you. When outspoken “anti-woke” advocates took issue with people rather than ideas, mocked their opponents while making themselves out to be victims, and began advocating for a worldview that left little opportunity for nuance or complexity, they began to embody many of the traits they criticized.

The way that Brodsky charts the devolution of “anti-woke” into its own intolerant tribe mirrors many of the behaviors that we know to be hallmarks of bad conflict: demeaning and alienating your opponents, failing to listen to what other people are actually saying, and generally promoting an us-vs-them mentality that pushes people to ideological extremes.

What makes Brodsky’s critique unusual is that she is writing from a place of personal experience. She has been a vocal critic of “woke” politics and people. She’s speaking to her own tribe, a well-documented strategy for diminishing partisanship:

Fighting an enemy can turn us into something we might no longer respect. I say this as someone who noticed that change in my own self early on, but I didn’t like what stared back from the abyss at me. So, I recoiled.

…

If we don’t want to risk losing our North Star, we must focus on what we stand for rather than only what we stand against. For me, that’s evidence-based reasoning, freedom of expression, authentic and respectful discourse, tolerance towards dissenting views, individual rights, and, well, curiosity.

You can’t fight misinformation with distrust alone

Regardless of how prevalent falsehoods are, truths are still much more common. Focusing solely on the abundance of misinformation may actually erode—rather than bolster—people’s trust in reliable information.

In a recent essay for the Guardian, mathematician Adam Kucharski draws on his research into the science of certainty to argue that we need to focus less on judging things to be immediately true or false, and more on managing our skepticism and learning to interpret whatever gets thrown our way:

If we focus solely on reducing belief in false content, as current efforts tend to do, we risk targeting one error at the expense of the other. Clamping down on misinformation may have the effect of undermining belief in things that are true as well. After all, the easiest way to never fall for misinformation is to simply never believe anything.

Rather than focusing on being alert to online falsehoods, Kucharski encourages readers to hone their own capacity to think critically. After all, he points out, most misinformation contains some kernel of truth:

When I’ve encountered conspiracy theorists, one of the things I’ve found surprising is how much of the evidence they have to hand is technically true. In other words, it’s not always the underlying facts that are false, but the beliefs that have been derived from them. Sure enough, there will be a logical fallacy or out-of-context interpretation propping them up somewhere. But it’s made me realise that it’s not enough to brand something “misinformation”: more important is the ability to find and address the flawed assumptions hiding among voluminous facts. We must give people the conceptual tools they need in order to spot skewed framing, sleight of hand, cherry-picked data, or muddled claims of cause and effect.

That means moving away from the idea that people are threatened by a tsunami of falsehoods. Calling information that is technically accurate untrue merely undermines trust. And if we issue warnings that most of the content you find on the internet is made up, it will distract from the bigger challenge of ensuring that technically accurate information is correctly interpreted.

There’s research to back up what Kucharski is saying here. For example, a 2022 study showed that if you care not just about how much unreliable information people believe but also the amount of true information that they believe, it’s much more effective to increase trust in true information than decrease trust in false information. This is because there’s much more true information out there than false information, so small changes in trust have a much greater effect. In sum, they write, “Our results suggest that more efforts should be devoted to improving acceptance of reliable information, relative to fighting misinformation.”

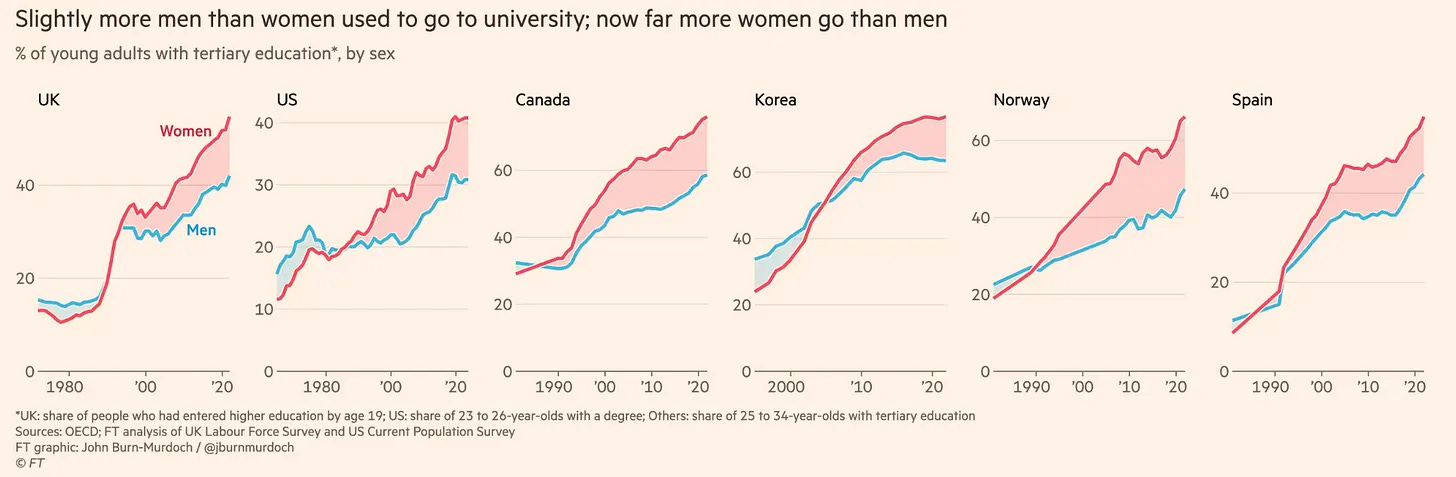

The practical path to promoting gender equity

“What’s the best way to promote gender equity without triggering backlash?” That’s the question social scientist Alice Evans poses in a recent post for The Great Gender Divergence. The answer, she goes on to argue, is deceptively simple. In her research across the globe, she found that campaigns that lift everyone up almost always yield better results:

To advance gender equality, it may be more strategic to build inclusive campaigns that gently expand what is considered acceptable [for women to do] while appealing to common values. Gender interventions will have the greatest impact if they tackle locally-binding constraints, with careful sequencing. Delivering shared prosperity is equally vital - especially for disadvantaged young men.

Evans’ research has shown that when you threaten someone’s status (in this case, men), assault their core values, or partake of exclusionary tribalism, you’re more likely to inflame organized resistance. Not surprisingly, people who feel like they’re losing out start to find reactionary politics attractive.

By contrast, when you work to build inclusive coalitions, create the perception of mutual benefit, and provide exposure to circumstances—in life or through cultural products—that broaden the boundaries of what feels appropriate and normal, and deliver shared economic prosperity, you can improve things for a historically disadvantaged group without leading others to feel that they’re falling behind. Crucially, right now any work in the gender equity space can’t lose sight of young men, who are demonstrably falling behind.

Image of the Week

I think we also have understand and counteract our very human and incredibly powerful fears of ostracism and humiliation by other member of the groups we belong to