Why Red Is Still Going to Vote for Trump - BCB #62

Also: A growing backlash against ESG goals, and a new book on Nasty Politics

Why Red is still going to vote for Trump

Trump supporters haven’t ignored the criminal charges against him; Trumps’ net favorability (favorability minus unfavorability) among Republican voters decreased after his June indictment for mishandling classified documents and again after his August indictment for election interference. But he’s still the frontrunner for the nomination by a wide margin. From a conflict perspective, this isn’t surprising.

In fact, Trump’s lead over other GOP candidates has widened. Support for Trump vs. other candidates went up among Republicans during the Jan. 6 hearings last year, immediately after his indictment for financial crimes in early April, and to a lesser degree after his August indictment.

It’s easy to dismiss this as ignorance or even malice, but Republicans are nearly half the country, which means they’re actually pretty average Americans. It’s entirely reasonable for his supporters to react this way, given their existing worldviews and social networks.

Recent polling data shows that Red’s confidence in the criminal justice system is at a mere 17 percent. Television and newspapers are among the least trusted, at eight and seven percent. Congress and the Presidency score even lower. If you believe that the media, the government, and the judicial system are untrustworthy, you’ll likely conclude that the indictments are not credible and that media coverage is unfair. Within a Red worldview, prosecution of Trump only confirms the theory that the establishment is out to get him.

If you identify more with the Blue side, perhaps a comparison to the Hunter Biden case will help explain how Red thinks about the prosecution of Trump. While there’s a reasonable argument that comparing Trump to Hunter is false equivalence, the psychological deflections are similar.

Blue media has consistently downplayed Hunter Biden’s tax fraud prosecution. When the Justice Department obtained a guilty plea from Hunter Biden, Blue thought the charges were too “harsh” and a “smear” against the Bidens. When two IRS whistleblowers testified that prosecutors were biased in handling the Hunter Biden case, Blue mocked Red for being obsessed with Hunter Biden. Yet the Justice Department is taking this seriously: just last week the Attorney General appointed a special counsel to oversee the investigations.

Neither side reacts objectively; and over a long period of time, partisan interpretations coalesce into a worldview where it’s logically consistent to interpret damning revelations as mere enemy action.

Red's growing pushback against ESG is reshaping finance

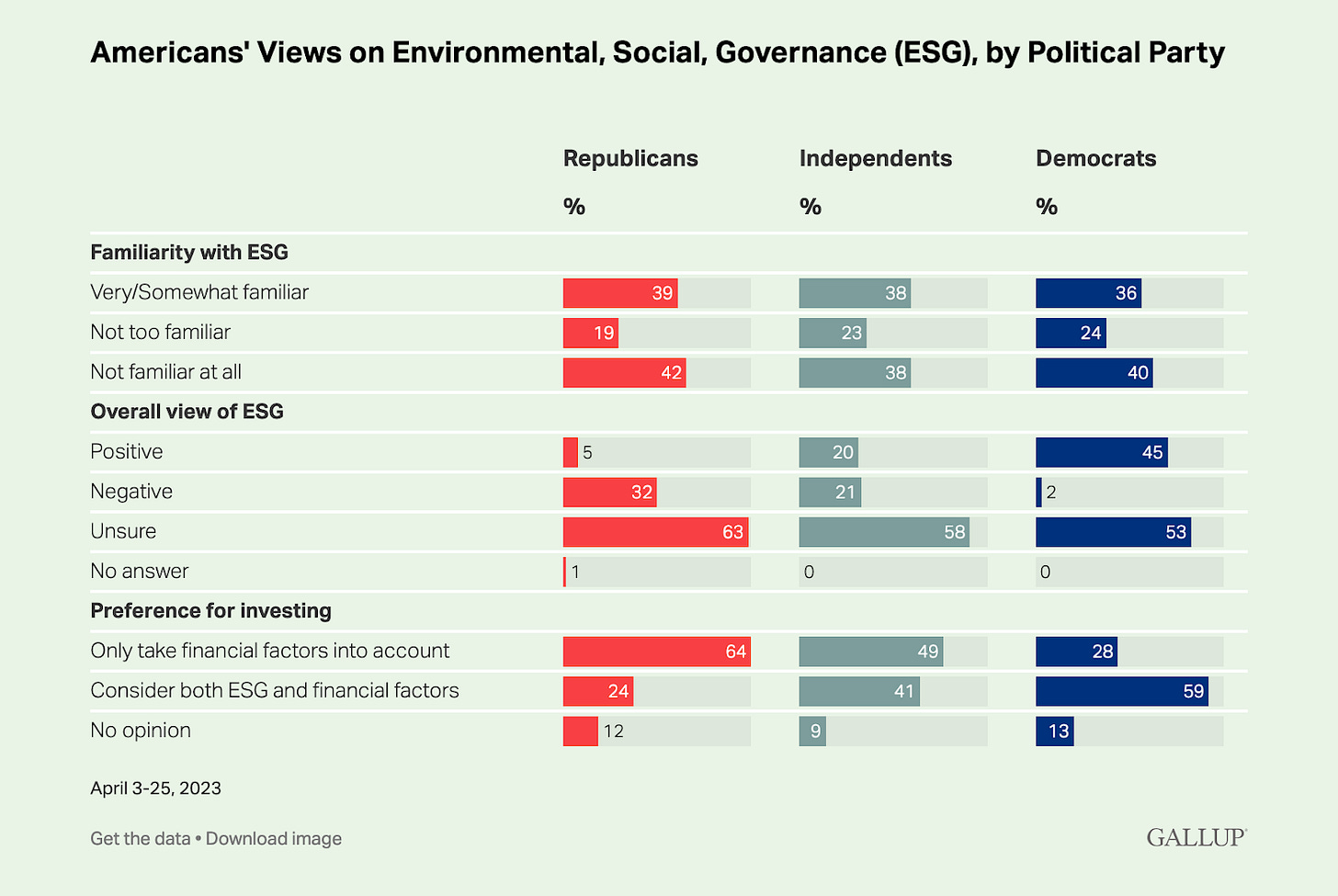

ESG stands for “environmental, social, and governance,” factors that many investors consider when deciding where to put their money, and a low-key social movement over the last several decades. Now several organizations are driving an anti-ESG counter-movement. Only 37 percent of Americans have even heard of ESG, but among those only five percent of Red view it positively, compared to 45 percent of Blue. This backlash is pressuring the world’s major financial firms to back off some of their net-zero goals in Red states.

The ESG movement has been aggressively drawn into the culture wars at the highest institutional levels. The fossil fuel industry, along with Red politicians like Ron DeSantis, have condemned ESG, increasingly calling it “woke.” A Red investor labeled ESG investing as “more insidious than communism or the Nazis.” And there’s legislation too:

So far in 2023, Republican lawmakers have introduced 165 pieces of anti-ESG legislation in 37 states.

Some leading global asset managers, like Vanguard and BlackRock, have backed off from their net-zero commitments and reinstated support for fossil fuel companies. In contrast, Democrats in Congress are pressuring JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo to cut ties with any anti-ESG groups. This controversy reveals the extent to which polarized politics now dictate the flow of money in the world’s largest financial institutions.

Book review: Nasty Politics: The Logic of Insults, Threats, and Incitement

Politicians often use insulting or threatening rhetoric against domestic opponents, even though, according to Thomas Zeitzoff’s new book, voters hate it. Yet this might not always be a bad thing for democracy.

Zeitzoff comes to this conclusion by studying social media posts, debates, surveys, news articles, and speeches, with a focus on case studies in Israel, the U.S., and Ukraine. In democracies, he finds that nasty politics follows a similar logic, regardless of where and how they’re used.

Insults, accusations, veiled threats, incitement, and actual violence are distinct tactics. But like other scholars of aggression and violence, I see different types of nasty politics sharing a core logic.

He believes nasty politics is driven by supply and demand. The most relevant factors influencing public receptivity on the demand side are the level of polarization and the perceived threat from the outgroup. At such times, “voters may view nasty politicians as tougher and better able to protect the in-group.” Yet these same voters, on average, hate nasty politics. Zeitzoff insists that “they aren’t lying when they say they don't like it.”

On the supply side, politicians sometimes use this strategy when they believe it’s their only path to winning. Minority groups or marginalized parties often find this strategy effective.

Nasty politics is the weapon of outsiders and losers. Its effects on democracy are mixed. It can be a legitimate tool for the powerless to grab attention. Or it can be a cynical ploy for incumbents to hold onto power. Nasty politics influences the kinds of politicians who run for office, and its repeated use can turn voters off from politics, and make them less likely to participate. Finally, the potential for actual violence from nasty rhetoric is always lurking in the background.

Nasty Politics’s demand and supply theory offers a new and robust model for predicting when politicians will use nasty politics and how the public might respond.

Quote of the Week

We're pretty uncharitable as a species. If you ask somebody about a deeply held position they have, “Why do people disagree with you about this?” the answer that you're probably going to get is “Well, they disagree with me about this because they're ignorant.” And if they're not ignorant, then they're stupid. And if they're not stupid, well, then they're brainwashed. And if they're not brainwashed, then they're evil. And it usually goes in that order.