Why Do Liberals Experience Worse Mental Health?

Also: the case for an American non-aggression pact #BCB 158

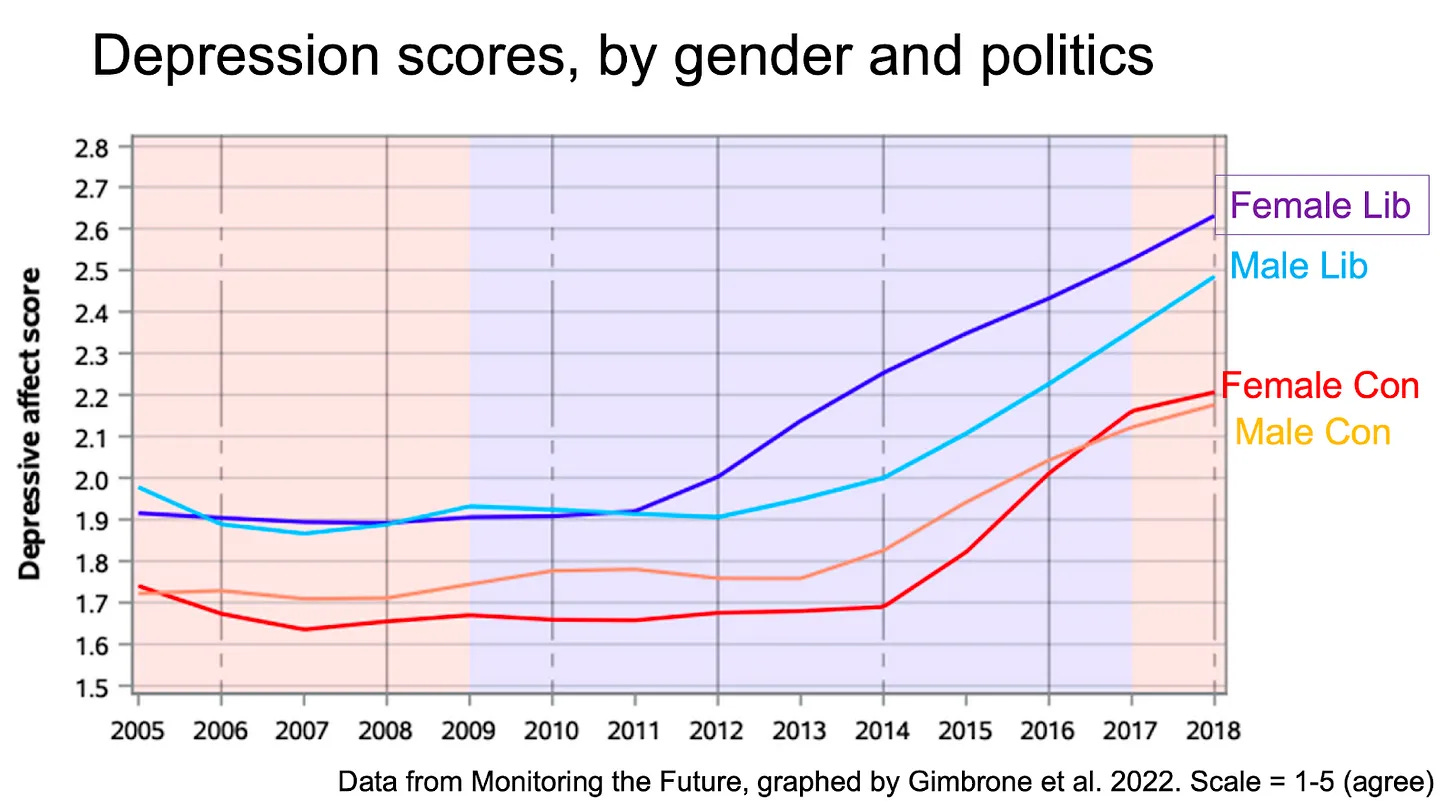

A number of different data sources show that liberals have worse mental health, on average, than conservatives – particularly young women.

One study by Catherine Gimbrone and colleagues analyzed mental health trends among US adolescents. From 2005–2012 there were only modest differences across ideology and gender. But starting in 2012, mental health among liberal girls deteriorated sharply, with depression scores rising 0.7 points on a 5-point scale. No other group saw such a sharp increase, though all worsened.

Red just loves this, arguing that progressives’ problems are the result of the lives they’ve chosen – less family oriented, less religious, alternative lifestyles, etc. Liberals might argue instead that they’re just more informed and more concerned about the current state of the world. (Although, the old idea that depressed people have more accurate views isn’t true.) Or it could just be that liberals seek help more often than conservatives, which juices the stats.

Even so, political engagement can be an emotionally unhealthy activity. Former progressive activist Sabrina Joy Stevens believes that modern activist spaces – especially online – reward emotional intensity, punish dissent, and treat distress as a kind of moral credential. The result, according to her experience, is that emotionally manipulative storytelling and rigid ideological conformity have left many activists not just ineffective, but also feeling deeply unwell.

My anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were at their worst when I was most invested in the left-wing ideology I’d built my professional and social life around,” she writes. “That all changed in late 2020, when I quit my job after months of growing disillusionment. I ‘graduated’ from therapy at that point, and my mental health kept improving.

Her point isn’t that liberal values are harmful, but that the scaffolding of many progressive institutions has become punitive and performative, rewarding outrage over strategy.

Alternatively, the Gimbrone study argues that liberal girls, especially those from lower-income backgrounds, bear the burden of political awareness without social power. They're more likely to speak out on issues like #MeToo or climate change, and also more likely to be targeted for it online. For some, liberal politics brings awareness but also bullying.

Other writers have pushed back on narratives around politics, pointing instead to the rise in smartphone usage, algorithmic curation, and the overall loss of autonomy facing Gen Z. “The first and simplest explanation is that liberal girls simply used social media more than any other group,” writes Jonathan Haidt. Another counterpoint: loneliness has also increased among young liberal girls, which seems unrelated to political causes.

None of this means one worldview is intrinsically healthier than the other, but it does invite a deeper question: What kind of political culture can turn emotional urgency into agency, not collapse?

The Case for an American Non-Aggression Pact

The last few years have seen an uptick in political violence, notably attacks on legislators, judges, and other public servants. The way out of this might be for political leaders on both sides to publicly forswear violence, argues a recent piece in Persuasion.

Their idea is that once violence gets going it is very difficult to stop, so Americans should commit to a mutual disarmament of culture war hostilities in exchange for pluralism, stability, and space to live differently.

Globally, it is now common for politicians and their parties to help transition their countries out of war and violence by agreeing to certain basic guardrails. Sometimes these agreements are known as “codes of conduct” or “nonaggression pacts.” They are not magical, but they can reduce violence by lowering the ambient temperature.

This isn’t just a theoretical proposal – it’s already showing up in small but meaningful ways around the country. Utah’s Republican Governor Spencer Cox convinced 22 other state leaders to appear in ads calling on Americans to “disagree better.” In Oklahoma, the governor signed a Dignity Pledge to elevate civil discourse. In Georgia, over 70 civic leaders have committed to nonviolence and trust in elections – part of a broader national initiative now signed by more than 7,600 officials and regular citizens.

The approach is gaining some traction: organizations like Braver Angels, More in Common, and One America are already modeling coexistence over conquest through dialogue programs, shared storytelling campaigns, and cross-partisan workshops – engagements which are open to the public. The idea is to give up on total wins and start negotiating terms of survival. In a country with wildly different visions of “the good life,” that may be the only way forward.

Quote of the Week

I consistently have ideologues on both the Left and Right explain to me why it's very good and important that they're bitter and hateful. They believe it makes them a better, more effective person; ironically, it only makes them more similar to the people they hate.