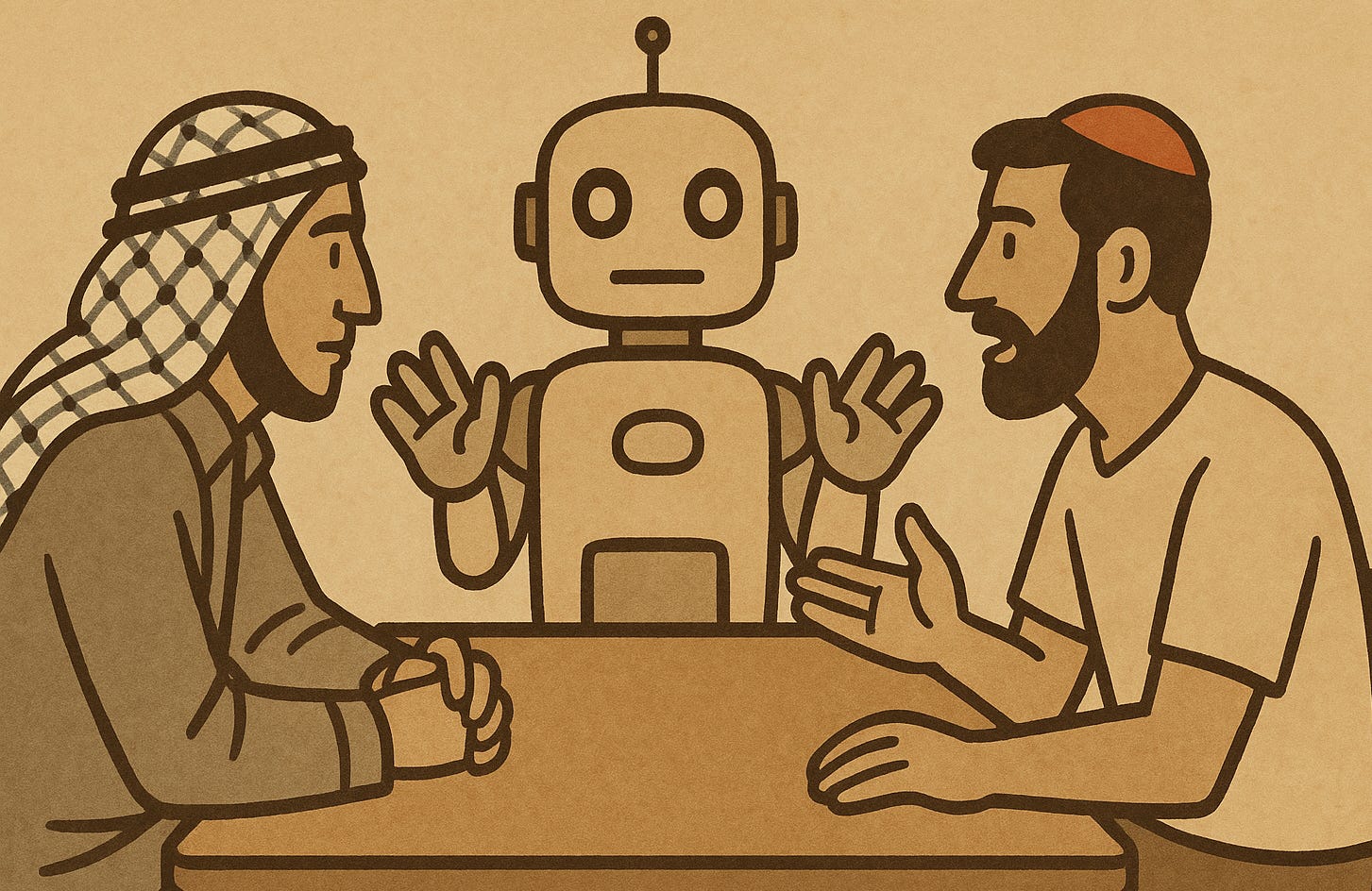

What You Can Learn from 4,000 Conversations Between Israelis and Palestinians

Adam Becker is building an AI-powered platform for difficult conversations - BCB #171

Not many people have the chutzpah to put themselves right in the middle of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, and even fewer of those are trying to build their insights into an AI-powered peacemaking platform.

In this podcast, Adam Becker shares his unique journey from tech entrepreneurship to facilitating thousands of conversations between Israelis and Palestinians. Along the way he discovered the power of small humanizing gestures, found that text-only conversations are toxic, and learned that the success of a conversation depends more on who talks than what they talk about. He’s distilling all of this into HeadOn, a data-driven platform specifically designed for the most difficult conversations. Plus: what Palestinians and Israelis misunderstand about the other.

Jonathan Stray: Hello everyone and welcome to the Better Conflict Bulletin podcast. I have with me today Adam Becker, who has moderated 4,000 conversations between Israelis and Palestinians after October 7th. Hi Adam.

Adam Becker: Jonathan, thank you very much for having me today.

JS: I don’t know anyone who’s done this many conversations, especially not in the last few years. How did you get into this?

AB: I got into this through a very unusual route. By training I’m a tech entrepreneur. I went to Cal [UC Berkeley] and as soon as I graduated I was trying to find a way into the Israeli and Palestinian conflict space to use tech and startups as a vehicle for effectuating change in that space.

At some point I began to gradually shift my focus to the American political culture wars scene. I created a platform to help conservatives and liberals speak more effectively.

This was when Trump was first making a credible bid to the presidency. When he won, I then shifted gears one more time and started an AI company to help Democratic campaigns do their fundraising more effectively. I did that for a few years. I moved from San Francisco to DC. I lived there on Capitol Hill until Biden won. By that time our app helped Democrats raise about a hundred million dollars. I moved to New York, I got deeper into the AI world and machine learning world.

And then October 7th hit. The next day I moved back to Israel, where I had grown up. First of all, it was just almost impossible to make it to Israel. You can imagine the airspace was quickly closing down and every airline was shutting down all their flights. My goal was to make it to Tel Aviv in the morning, and to simply have a thousand Israelis speak to other people from around the world.

I wanted to see first of all, whether Israelis were able to articulate their own position because I kept hearing a slightly different narrative from the one that Israelis tend to embody. So there was a lot of misunderstanding. And on the other hand there’s a lot of misunderstanding among Israelis about what the world was actually critical of Israel of. So I thought it would be very valuable to try to open some conversational channels. That’s how it began, in the early days of the war.

Fast forward a couple of years, we’ve been facilitating thousands of conversations on the platform.

JS: So what drew you to trying this insane thing?

AB: Have you ever been on these apps like the Omegle and Chatroulette or Monkey app? You have those apps that just connect people randomly with one another.

And in Israel, during a time of war, everybody could see that I’m calling in from Israel. And it’s an immediate politically charged confrontation. That’s how every conversation began.

I became absolutely obsessed with trying different techniques to de-escalate those conversations. When something starts like this, is it even salvageable? Over time, I’ve started seeing patterns, and I was like, “My God, this is not just salvageable.” We’d end up having incredible conversations, even though they start out with them doing a Nazi salute.

Oftentimes, we end up becoming friends and then they give me their phone number and we’re exchanging links on WhatsApp and I send them some links from the Better Conflict Bulletin. I started seeing that there’s a lot of techniques for de-escalating.

As I said at the beginning, I don’t have a background in conflict resolution but I built up a lot of intuition for how to do these things. And I started seeing actual effect, and actual impact. And it was shocking to me.

Humanizing gestures

Just to give you some examples, I would pretend that my mom was calling me and I’d say, “Sorry, can you give me a moment? My mom needs help.” And then I’d talk to my mom for 10 seconds. And when I’d put down the phone, immediately something changed. They’d see me as a human.

I would take my phone or my computer to the kitchen and take out soup and heat up the soup. I’d see that as soon as they’d see that I’m a human, it’s a totally different story and they start reacting differently.

I started seeing all of these patterns, and at some point it hit me that this is a data problem. If only we had sufficient data about how to de-escalate. I shouldn’t be doing all this A-B testing. It shouldn’t just be me. So at some point we started building AI to help us almost design conversational experiences.

If only we had sufficient data about how to de-escalate.

I’ll give you another touch point of how transformative these experiences were. One time, I was connecting with a woman in Tunisia. And the bright screen was lighting up her face. She was laying in bed. And she saw that I’m from Israel and she didn’t say a word. She just started singing the Lucy Thomas rendition of the Hallelujah song. I’d never heard it before, but she played it. Our eyes were just transfixed. Here you go, like in the middle of a war and this girl is singing me the Hallelujah song. I had goosebumps.

So I realized pretty quickly that this is a different type of experience from an academic, ceremonious negotiation exercise at Camp David, right? I’m in the gutter with a bunch of people, but it seems like there’s millions of them. And it seems like there’s actual impact that you can drive here.

The role of conflict outsiders

JS: Then at some point you thought, “I want to try connecting Israelis and Palestinians.” So how did you go about that?

AB: When the conflict had globalized after October 7th, that is when every single person around the world started having strong opinions about what was happening, I started seeing other people as potentially very valuable in this conversation.

In general, they might have a pernicious effect on the conflict, but if given the right tools, I thought and hoped that people who are not in the conflict, who are not as traumatized as the Israelis and Palestinians themselves have a role to play. And we need to find ways to pull them in.

And so the first thing that I did was not just go to Israelis and Palestinians, but go to Americans. Go to Americans, go to Europeans, go to North Africans, go to anybody else who is interested in the conflict and who is interested in talking to Israelis and talking to Palestinians about what’s happening on the ground.

One of the things we did is we just started walking around in Israel and in the West Bank and recording people answering questions that the rest of the world submits to a YouTube channel. And we started getting hundreds of thousands of views. And then we invited those people from those views to come and actually extend the conversation into a more meaningful session on our platform.

JS: Do you still have this YouTube channel? Is it still going?

AB: Yeah, it’s still going. It’s been doing really well for for 15 years. So I go to Israel about twice or three times a year and we go and we do recording. The guy who started this, his name is Corey Gil-Shuster. Anybody can find it. You could just type “The Ask Project.” Absolutely fascinating window into what people actually say when you ask them questions. There’s a lot of disagreement about whether that’s what they think, but that’s certainly what they say when you catch them unsuspecting in the middle of the street in Ramallah or Jenin or Tel Aviv.

So in the middle of the war, there was a lot of appetite to understand what Israelis feel, and how Palestinians in the West Bank are experiencing it. So that was one source of interest.

And it’s continuing to go. And so we’re still getting a lot of people that are coming by having watched the channel.

Aside from that, I also wanted to see what it would look like if we brought interns to speak. By interns, I mean American college students who wanted to get exposed to different ideas. They were looking for a space in which to do this. And we onboarded about a thousand of these interns.

JS: So you’re recruiting American college students as “interns” to your platform, your company. What was it called at this point?

AB: So right now it’s called HeadOn. At the time it was called Dugree, which is both a play on “do you agree?” and also it’s a word in Arabic and in Hebrew that both understand, it means “straight up”, “no BS conversation.”

Can we start to envision an infrastructure for scaling these conversations?

JS: I see, okay. So, you recruit Americans to this Dugree platform to have conversations with Israelis and Palestinians in Israel and the West Bank, is that the idea?

AB: And one another.

JS: They are talking to one another, and also to people on the ground?

AB: That’s right. And more and more people from around the world. We had Islamists from Egypt and we had radicals from all over the world and they all got to mix together in a fascinating blend.

We just started by seeing, what it looks like for people to have these conversations in the first place. And can we start to envision an infrastructure for scaling these conversations?

JS: And these are one-on-one conversations, no mediator or facilitator?

AB: No mediator or facilitator. We try to build some guard rails to keep the conversations constructive with the full humility that we don’t know how to build guard rails, and that guard rails are likely to be very context-specific and context-dependent. And ultimately we will need to find generalizable and scalable guardrail mechanisms.

It took me a long time to get deeper and deeper into the relevant literature on what works and what doesn’t work — at least from an academic perspective. A lot of that is thanks to you and to the Better Conflict Bulletin, so I appreciate all the work that you’ve done. At the time that we were starting — we had these thousand interns — we knew absolutely nothing about conflict resolution.

Trying and failing and trying again

JS: So how’d it go? Did conversations blow up? Did they resolve? Did people learn things? Did they come back? I’m so curious, if you just put people in a room, what happens?

AB: It was absolutely incredible. People loved it and everybody reported moderating their beliefs, and more than that, feeling closer to people from the other side and understanding them better. And then it blew up and then it became too toxic. And then we had to start over again. And we have to try to reimagine things. So that’s happened for a few cycles now.

But I can tell you that the American college students, many of them were totally fine opening up. I found I was incredibly impressed with their ability and willingness to have those conversations and to do this repeatedly. People would come back day in and day out to have these conversations.

I noticed a stark difference when there was an Israeli or Palestinian in the room with these people and when there wasn’t. It’s a totally different texture of a conversation.

JS: So are these all one-on-one or are you now having group conversations?

AB: Both. But it was very difficult because as soon as anybody saw which other conversations are taking place, people would always default to a conversation that was already taking place. If two people were talking, 30 other people would join the platform, and there would be a 32 person conversation. People didn’t, on their own, fragment.

You have to force the fragmentation. Otherwise they all congeal into a single conversation that ends up changing. Its nature changes completely because now it’s no longer an opportunity for two people to be vulnerable. Now it’s a stage and there’s an audience and there’s stakes and the stakes are of performance and it changes the nature of them completely.

JS: I guess if there’s more visibility into what other people are doing or there are comments on the side, then it can become toxic?

AB: Yeah, that’s how it became toxic.

I think that ultimately the trajectory of experience for each person is a function of their motivation. For the people who are very, very good at having these conversations, they don’t necessarily want the one-on-one, because they feel like their voice needs to be broadcasted to more people. They would like there to be a bigger audience. And so you have to balance meeting their needs for having a larger audience versus what actually makes for a productive conversation.

The primary thing that has attracted people is a sense of curiosity.

The primary thing that has attracted people is a sense of curiosity. And that’s the thing that we’re leaning hardest into as well. People just want to learn about the space. They want to come and ask questions, or perhaps they want to refine their own intellectual understanding of the space.

Second is oftentimes just loneliness. You know, we have a loneliness epidemic at the same time as we have a polarization crisis. And I’ve always thought that perhaps those two could be solutions to one another. So just actually having a space where you can come and reliably meet somebody else and have conversation about a topic you care about. I think that’s a major driver. And it changes how we design the experience.

The third motivation is just to influence and to change people’s minds. And to prove why the other side is wrong and to correct a misunderstanding that they are perceiving in the discourse.

The next one is a sense of combat. People do like to fight about these things. It’s almost like intellectual jiu-jitsu for a lot of people. I think this is more true of people who are not in the region facing the conflict. There’s an intellectualizing of the conflict. Very different when you speak to Israelis and Palestinians on the ground, it tends to be much less of that.

And then the last thing is entertainment. Some people just want to come and watch a battle. They want to see how these things actually unfold and there’s something fun about this.

So we don’t lean very hard into the latter two, into combat and entertainment. Although we think that it’s necessary to create healthy spaces for those as well. Because some people might come with this energy, but then be redirected towards perhaps like more curious and humble energy. And we think that there’s a need for that type of pipeline. So yeah, depending on what the motivation is, we ended up seeing that very different things were.

JS: How are you monitoring what’s working and not working?

AB: I’m trying to be in many of them, and I often even act as the AI behind the scenes. So sometimes it’s the AI and sometimes it’s me doing various things, perhaps like sending a new prompt to the people.

The medium matters

AB: By the way, everything is audio-video at this point. One thing that we’ve taken away is that text is a radicalizing technology.

JS: Did you experiment with text chats?

AB: We did, and we do because a lot of people prefer text. It’s a very thorny topic for us.

We have drawn a distinction between a text chat and a text channel. A text chat is going on while an audio-video conversation between participants is taking place. Those don’t blow up nearly as much.

Text is a radicalizing technology.

But if it’s just text as a channel, where that is the primary mode of interaction and people have a lot of time to get really deep into their own heads and to just download onto the channel a very specific worldview without getting immediate pushback about specific moves, that blows up. And so we have not been able to, I think, create a very healthy text channel space.

And it doesn’t blow up most of the time. 85 % of the time it’s okay. 15 % of the time it’s a disaster.

For long texts, I believe that the AI should be the one generating texts. I can trust the AI to generate texts more so than I can trust the humans to do it. .

What makes a successful conversation?

AB: Now, how do I know that the conversations are going well if I’m not in all of them?

First of all, we see if people stick around, if people want to be reconnected and re-paired with the same people over and over again, because they feel like they’re making progress.

JS: So, some people actually come back and talk with the same people the next day, the next week?

AB: Yes. At one point, we had a college student who had just come back from Auschwitz on a trip, and another American who was Native American and was very sympathetic to the Palestinian cause. And the two of them had fascinating conversations. And they kept messaging me afterwards, “Could you please pair us up together next week?” And then the next week. And then the next week.

AI for conflict resolution

JS: So you built some AI into the platform early on. What did it do?

AB: So I’ve always believed that the AI should be prompting us to get us to go deeper into what we think and why we think.

And so the AI would pick prompts. People might come into the conversation. They would know it’s going to be Israel, Palestine, but they wouldn’t know the specifics. They talk about, let’s say, the wall. And then the AI might give some quotes from Wikipedia and try to see if people engage with them. It might ask them, “What do you guys think about this?”

Next it might put a very different type of screenshot with a very different clause that is very supporting of the wall and get them to then react to that. Perhaps ask them, “How much do you agree from one to 10 about that?” And then it would plot the people’s responses. This is for larger groups where you really want them to get a sense of where the entire crowd is.

I have grown to believe that AI shouldn’t be a moderator of a conversation. It should select the right people at the right time for the right topic.

JS: Is the AI a conversational participant, or how does that work?

AB: We tried it all. We tried everything. Right now it’s less of that.

I have grown to believe that AI shouldn’t be a moderator of a conversation. If once we have a superhuman AI, I don’t imagine it would be like Oprah. I think it would be more like a Cupid. It would do the pairing better. It would create the environment for the better conversation. It would select the right people at the right time for the right topic better. Not just wait for a thing to blow up and then step in. That’s too late. You shouldn’t have gotten to those octaves and those volume levels in the first place.

I think there’s a Thomas Jefferson quote, “Don’t just tell me which books you read, but in which order you read them.” I think there’s a similar sentiment here. Who you pair up with makes an enormous difference. And the fact that you hear from somebody who disagrees with you is insufficient. I don’t think that’s enough. You really have to engineer the proper conditions for this type of contact to be effective.

And it could very easily become worse. In the early days of social media, they said we were trying to connect everybody. Israelis and Palestinians connect in the West bank and the checkpoints. You could easily replicate the checkpoint at scale. That type of connection and contact isn’t optimal.

For example, we would have some, let’s say American Jews, older gentlemen, who had a very difficult time speaking to Palestinian youth. And the Palestinians would complain, “We can’t talk to this guy. It’s absolutely impossible. And you have to kick him off the platform. They’re really toxic.”

Nevertheless, when I would have conversations with them, those were incredible conversations, some of my favorite conversations. And I realized you really have to be quite precise about who the conversation is between in the first place.

The pace of trust

AB: When people have a hypothesis class about how the world could be, they model the world in a certain way. And when you introduce a radically new concept, it blows up the hypothesis class. And now so many things could be true, that they end up becoming even more entrenched in their perspective. And the us-versus-them increases. It’s shocking.

I would put two people in a room who have — many Israelis had never spoken to a Palestinian in their lives and vice versa. And then they hear the arguments and the narrative of the other side, and they would immediately entrench in their own position and refuse to engage. And they would radicalize. I could see that in my own eyes. Sometimes I feel it, too. I myself feel, you know. I shift to the right when I speak to some people. It’s almost like, now I have to re-examine every node of thought I have about the conflict and it’s too much. And so I shut down.

Alternatively, you have learning. Learning is a very gradual expansion of the hypothesis class in a way that nevertheless makes me feel safe.

And then they hear the arguments and the narrative of the other side, and they would immediately entrench in their own position and refuse to engage. And they would radicalize

I can examine this. If you have somebody who’s on the far right and Israeli politics, they could speak to somebody a little bit to the left of them. Their hypothesis class and their brain grows responsibly. I think in so far as they find themselves in safe settings, they can learn.

I think it begs a question of what the goal is. The goal is not to get people to agree on things. I am not even sure that that’s a desirable goal. As you often say, it’s about transforming conflict from something that is unhealthy to something that is more healthy. So our goal is not to get everybody to agree.

For example, as soon as we scale out and we have people speaking about whether the earth is flat or the earth is round, I’m not sure that they need to find common ground.

What we’re trying to optimize for is the accuracy of theory of mind.

Right now, a lot of Israelis imagine they know what Palestinians think, but they’re wrong about it. And Palestinians think they know what Israelis think and they’re wrong about it. And you published another piece a few weeks ago about Democrats and Republicans or conservatives and liberals in the U.S. They are consistently wrong about what the other side actually thinks.

Misconceptions and meta-perceptions

JS: There’s an academic name for it, which is meta-perceptions: your perceptions of what the other side believes. Let’s get down to brass tacks here. What are the things that Israelis most need to learn and Palestinians most need to learn to improve their models of the other side? What have you actually learned at the object level?

AB: When a rocket comes flying towards you and is chasing you into your shelter, you don’t interpret this violence to be political. You interpret this violence to be hate driven and because of your identity.

I never drove on the highway in Israel, and heard the sirens and had to get out of the car and hide under the car and thought to myself, “I wonder what political points they’re trying to make to me.” That never happened. It’s like, “They hate me for who I am.” That is the default feeling. And that may or may not be true, but when you speak to a lot of Palestinians, they say it’s not true. So that is not how Palestinians understand the nature of their violence.

What we’re trying to optimize for is the accuracy of theory of mind.

I think that a lot of people in the Israelis’ positions have interpreted politically-driven violence as identity based. For various reasons, some of them I think are kind of like good faith reasons and some of them are for cynical reasons.

I think it’s easy for politicians to exploit political violence and translate it as identity because then there’s nothing I can do. I’m a Jew, I’m an Israeli, I live here. There’s nothing I can do. If they don’t like it, at some point they’re going to have to make their peace with it, but that’s it.

And then it’s also easy for Israelis to misinterpret Palestinian political violence because oftentimes Palestinians use identity-based language and hate-based language to describe their own violence. And so it’s also true that Hamas often don’t talk about Israelis. They talk about Jews.

And they talk about the need to kill Jews. That’s also true. So there’s also a layer of anti-Semitism that at this point has become rooted in the society. Also for obvious reasons, they’ve been in conflict with Jews for the last hundred years. It makes sense that they at some point would start to dislike Jews. But none of that is shocking.

So, so on one hand, you have cynical players who might be exploiting political based violence and translating it as something that is identity based. So that’s, think the more cynical interpretation. And I think that’s probably true in this case. And in many other cases where people are feeling hate driven violence.

On the other hand, you could also understand why many Jews and Israelis would feel that the violence is hate-based and identity-based because it’s often framed as hate-based and identity-based by the other side. So when Hamas talks about killing Jews, they don’t necessarily say killing Zionists. They often use the word “Jews.”

And so Jews are sensitive to this. When you hear this, they say it’s because of who we are. So there’s also obviously a layer of anti-Semitism that is driving some of this, which again is also understandable given the fact that they’ve been in conflict with the Jews for a hundred years. So it would not be shocking to find some amount of Jew-hatred on that side. But by and large, I think the main motivation of the violence isn’t identity-based, but political.

By and large, I think the main motivation of the violence isn’t identity-based, but political.

I’ll give you another example. Yesterday I had a conversation with — so right now we’re a team of Israelis and Palestinians — had a conversation with a Palestinian engineer of ours from the West Bank. And I asked him about his experience with the prisoners being released, and what he feels about the fact that some of these prisoners have obvious blood on their hands? Like, they perpetrated the lynching in Ramallah and many bus bombings and they’re all getting released. And he said, there’s a person from their village that murdered an Israeli woman, but not out of hate.

He just tried to rob her and it didn’t go right. And so he killed her. And now he’s on a bus back to the village near Hebron and the village refuses to accept this man because he killed a woman or a child and it’s unacceptable. The village said, you’re not welcome here. Whether or not it’s true, the fact that this guy believes this to be true is, would shock virtually every Israeli into complete disbelief.

Over the last, whatever, 48 hours I’ve spoken told Israelis about them not accepting a murderer into their village. They [Israelis] didn’t understand it. So again, it’s a misperception and faulty theory of mind.

JS: What is the Palestinian misperception of the Israelis?

AB: I think it’s a more tricky one and it comes down to the experience of colonialism. I think that Palestinians experience Zionism as colonialist in nature. Which is easy to understand why they would experience it that way.

But to the Israelis, that is not the experience. To the Israelis, it is truly a national liberation movement and a incredibly pragmatic and deeply unideological one, at that. It is just an attempt to rescue millions of Jews from the ovens of Auschwitz, or from pogroms in Eastern Europe, or from Arab domination and oppression. And that’s it. And this is their place and it’s always been their place. And in their mind, they’re open to sharing it so long as they themselves experience it safely.

And it’s not about coming and occupying and dispossessing because they think they were there first. The rhetoric that settlers today often evoke is religious-based arguments. Those are not the arguments that have motivated the generations of Zionists who settled the land.

I think there’s this and also the religious versus national component. Palestinians see Judaism as a religion. Jews by and large see Judaism as a people. And it makes all the difference in the world for the Jews. It isn’t that easy to convert into Judaism and Jews don’t try to proselytize.

It makes a big difference for why therefore the Jews don’t think this is just a theocracy. This, in their mind is a safe space that they can call home. Where they can finally be safe because the entire world has time and time again demonstrated its willingness to kill its Jews. So that’s how the Jews and the Israelis see it.

For the Palestinians. Oftentimes it feels like it’s the French in Algeria, or it’s the British in India. And I understand why they experience it this way, but that is not at all how the Israelis experience it.

JS: What do you say to a Palestinian who’s watching [thousands] of people being killed in Gaza? How do you have a conversation that starts to get past that? Many people say, “the only way the path to peace is to share the land in some way.” How do you even begin to have that conversation?

AB: The question that I would ask is “who should begin to have that conversation?”

It might not be the case that I, as a secular Israeli-American, should have that conversation with them. It depends on their disposition and intellectual flavor, and how they have conversations, and what makes for good conversation for them.

When you speak to Israelis and Palestinians, many of them are deeply religious. It could be that the pathway between a religious Israeli and a religious Palestinian is much closer than passing through me. Maybe I’m not the right person here. Maybe my job is to just develop the infrastructure and connect them.

The Jews in the Middle East will be safe once the Palestinians are free. And the Palestinians will be free once the Jews are safe. And so we hold the key to each other’s future.

I would ask a lot of questions and I would collect a lot of data about who those people are.

What would I say? I think it’s a fairly simple formula in my mind: The Jews in the Middle East will be safe once the Palestinians are free. And the Palestinians will be free once the Jews are safe. And you can’t have one without the other. And so we hold the key to each other’s future and none of us is going away.

We’re here to stay. The Jews are there to stay. The Palestinians are there to stay. There’s millions of each. They’re not going anywhere. We’re going to have to find a way to make it work. One state, two states, however many states, I think that’s ultimately going to be a function of trust and a function of that meta-perception.

If we think the Palestinians are just going to try to kill us the moment they get the chance, we’re not going to sing Kumbaya and be in one state. But we might, if they take various steps, together increase trust. And as trust increases, I think lots of different solutions show up on the horizon.

So I think the question in my mind is what can Israelis and Palestinians do in order to slowly increase trust so that more solutions can show up?

AI for peacemaking

JS: Are you recording all of the data about who’s in the conversations and are you recording the conversations themselves? Are you running analytics to start to build models to understand when this is going to work?

AB: When we do, it’s very clear. Sometimes we don’t. If people prefer not to, then we don’t. Some things are metadata so they certainly get registered. So who’s in a conversation, regardless of actually recording the audio and video.

In the case of audio and video, we have defaulted to transcribing. We save the transcription, but only temporarily, and then we try to get rid of it. We don’t want to come back and quote people out of context. I don’t say recording, I say we’re learning from it because the recording itself becomes, is discarded.

JS: What are you actually using this training to do? What’s the training objective?

AB: So the goal is a very long-term goal. The goal is to reduce that meta-perception gap.

You can think about it like a policy. So given the environment, there’s various actions that the AI can take. And which actions should it take given that long-term objective of, let’s say, reducing that meta-perception gap.

And there’s different ways that you can model the meta-perception gap. In the literature on contact theory the idea is to increase the probability of a prejudice-drop. Even when you think about a prejudice drop, there’s a lot of different ways that you can think about this. Are they ideologically more aligned or are they just more affectively more aligned? Do they just not hate each other anymore? And you can come up with a bunch of different features. You can just do a lot of feature-engineering to figure out whether they hate each other.

People are not coming in because they think that here’s a space for them to have a compassionate conversation with the other side. I cannot give them that impression.

JS: How do you find that out? Do you give them surveys? Do you analyze the transcripts? Where are you actually getting the signals?

AB: Only analyze the transcript. On occasion, we will surface questions to the user, but I try to limit that. I suspect that would be gold standard if we can keep bothering them by asking them to fill out surveys, but I need to think of scale.

People are not coming in because they think that here’s a space for them to have a compassionate conversation with the other side. I cannot give them that impression. If I ask most Israelis and Palestinians, “Do you want to come and have a compassionate conversation with the other side?” They say, “The other side needs to die or get the hell out of here.”

That’s the energy, and we have to lean into that energy. So if I say, “Okay, do you now like them a little bit more?” they’ll say, ‘I don’t like this platform.” So I’m very, very careful about that. Which is also why the platform is called HeadOn. It is more confrontational and it’s okay. It’s the space for safe disagreement.

But in real time, the AI can also ask clarifying questions. Clarifying questions, by the way, is another feature that the AI can distill from the transcript. Are you actually asking them questions or are you just delivering points? Are you asking them questions that would try to demonstrate that you’re interested in how they’re doing it or not?

I dug into a couple of textbooks on conversation analytics. And I got inspired by some of those, like the question to statement ratio. And all of these things are things that AI can do decently well just from transcript.

JS: So, it sounds like you analyze the transcripts with some sort of classifier or estimator which tries to figure out what these people think of each other, and then use that as a long-horizon training goal.

AB: That’s the idea.

And the easier way to do it now is to build a very large compatibility matrix. You could even just ask the AI to be a judge. How good was the interaction between them towards reducing their bias and increasing their trust? Give it from a one to five or whatever. And then you have a big matrix of person by person. You can also now start to overlay topics. So then you have like a person by person by topic.

So now when two people show up to the platform, roughly at the same time, the AI can say, “These two people should have a conversation about this topic. I have even cached it.” You could do this offline. So this person and this person and that topic is likely going to be a very good conversation.

So now you show up to the platform, boom. I drive from cache and I show it from the short-term memory and I can show you the opportunity to participate in that conversation.

JS: So it’s kind of like a conversational recommender system with participants on a topic. Do you actually have something like this working?

AB: So the one that I just said with the compatibility matrix, that one we’ve been doing that for like 10 days. So almost done building the v.0 of that.

Another thing that we’ve done is a cluster analysis on topics, which proves fascinating also. What topic tends to follow another topic? When they’re speaking about this, are they likely to talk about that? If they’re likely to talk, what is the semantic evolution? If they’re likely to go from A to B, but then in B, they’re likely to fight over B, maybe we should wait on that or maybe we should pull in another person. And if that other person is in the room, we think that the probability would be reduced of it escalating.

So you could play all sorts of games like that once you actually model and simulate how the conversations are likely to unfold.

Inspirations

JS: Who inspires you in the conflict resolution space? Who are you most excited about learning from and working with?

AB: There’s a lot of good people in this space. Many of them I found through you and your research. Again, the person that I have seen is absolutely phenomenal in having conversations about this — to be honest, I have not found a single person who has better conversations about Israel Palestine — is a man I found on YouTube. His name is Adar Weinreb.

He started a YouTube channel many years ago, called The Great Debate. And now it’s just Adar Weinreb. I reached out to him immediately and asked him, “How come you don’t have millions of views yet? And how do I support you?”

And now he’s my co-founder in this project. He’s able to deploy a deep compassion and a capacious feeling of both sides with an erudition about the conflict itself. And I had not seen anything like this yet, to be honest. So he goes to the West Bank now on a monthly basis and brings Palestinians and Israelis together.

Ali Abou Awad in the West Bank, this has been absolutely fascinating to listen to as well. He came out of the Israeli prison, I think, many years ago. And he started a couple of organizations. One of them is called Roots in the West Bank.

Hearing him speak, it sounds like he actually understands how Israelis think. One time we recorded a 60 second clip of him speaking and posted to Instagram. I thought to myself “That will work on Israelis to open their mind about what Palestinians desire.” And as soon as we put it online, you actually saw a bunch of Israelis saying, “Never considered that perspective before. Fascinating.” And it’s just because he had that theory of mind.

JS: I have to say this is one of the meatier podcasts we’ve done. It’s rare to meet someone who’s really in the trenches trying to figure this stuff out. And at the same time, thinking about all of these advanced AI possibilities. So it’s really been a lot of fun. And I know we’ll have more conversations in the future.

AB: Jonathan, thank you very much for doing all the work that you’ve been doing. A lot of this, as I said, has been inspired by your work and your writing. And I look forward to reading more and thank you for having me on.

JS: Awesome, I’ll see you next time.

Great interview! Can Adam share more about why text-based conversations don't work? I can totally see this; text is alienating and so much more open to interpretation. He says that about 20% end in conflict. Is there anything special in these 20% in terms of words used or the type of people who participate or any other factors?