We Have to Talk About Immigration

Tips and facts for a sensible conversation - BCB #168

Immigration is at the center of current domestic conflict, as the Trump administration sends in National Guard troops to protect federal buildings from anti-ICE protestors. We, meaning citizens who disagree with one another, are going to have to talk about it.

This is not an easy thing to write about, because so much is at stake for so many people. The stakes are high for immigrants (whether legal or illegal) and their families and communities, obviously, but also for the rest of us. However you feel about immigrants and immigration policy, you’re likely to feel strongly about it.

And it’s a crazy topic, full of contradictions. Both deporting lots of people and giving them all a path to citizenship are popular! Immigrants have never been less safe in this country but support for immigration is way up this year!

Even choosing language to talk about this issue is hard. Both “illegal immigrant” and “undocumented immigrant” are going to rub many people the wrong way. Following Tangle and Pew Research, I’ll try to sidestep that linguistic argument by calling them “unauthorized immigrants.”

Legal and illegal immigration have different politics

One of the reasons conversations about immigration are hard is that people talk past each other in all sorts of ways. As a first step, let’s be clear on the distinction between authorized and unauthorized immigrants, because the conversation around these two categories is very different.

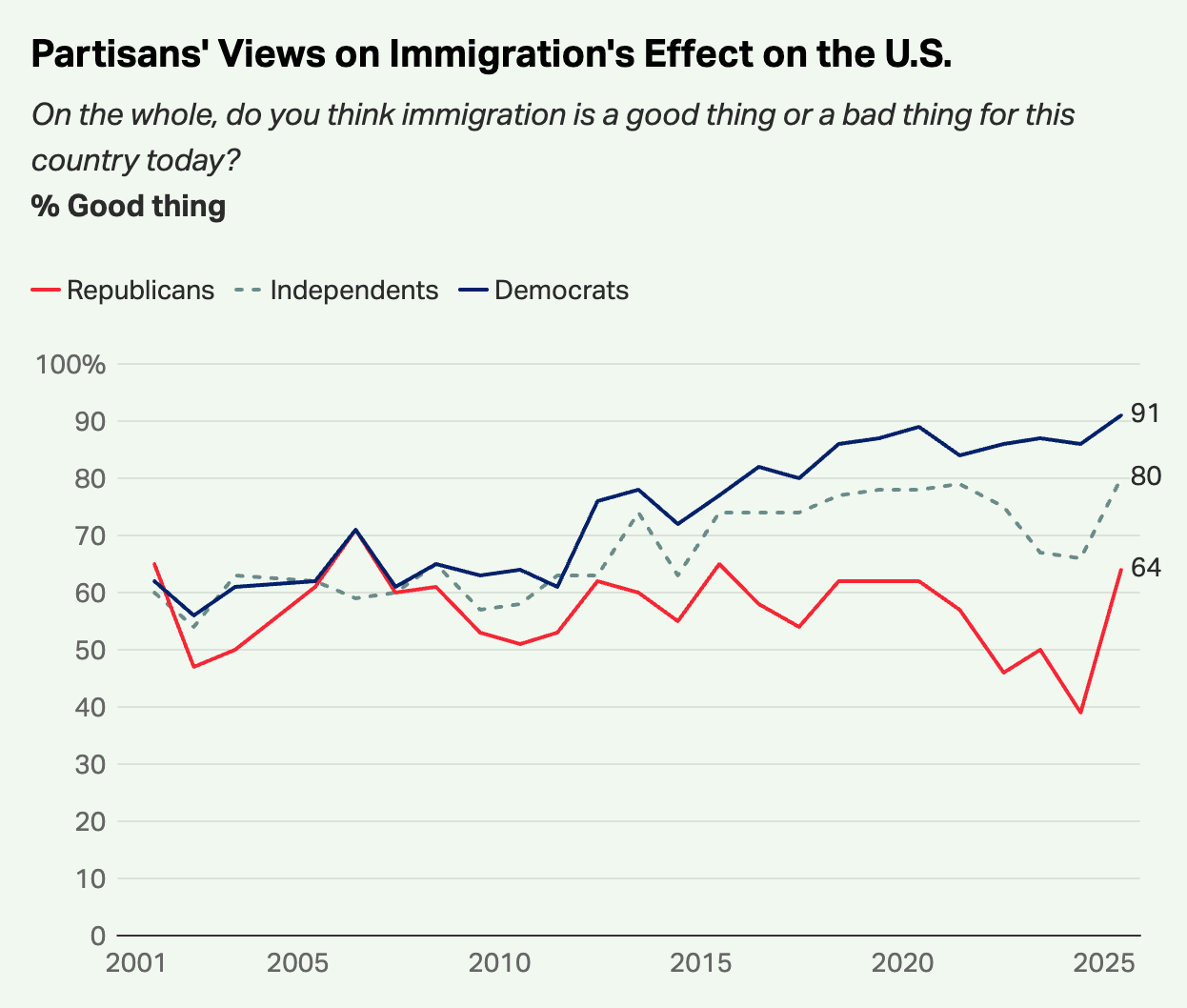

You may not know that support for legal immigration has been increasing across the board since Trump’s election. In fact, support for immigration rebounded after 2024 to a record-high of 79%.

The discussion around unauthorized immigration is different.

Despite rising support for immigration generally, despite masked government agents grabbing people off the street (I can’t believe I have to write that), despite Trump’s falling poll numbers on immigration… the Democrats are still far less trusted on immigration. This demands an explanation, and I think there’s merit to Josh Barro’s theory:

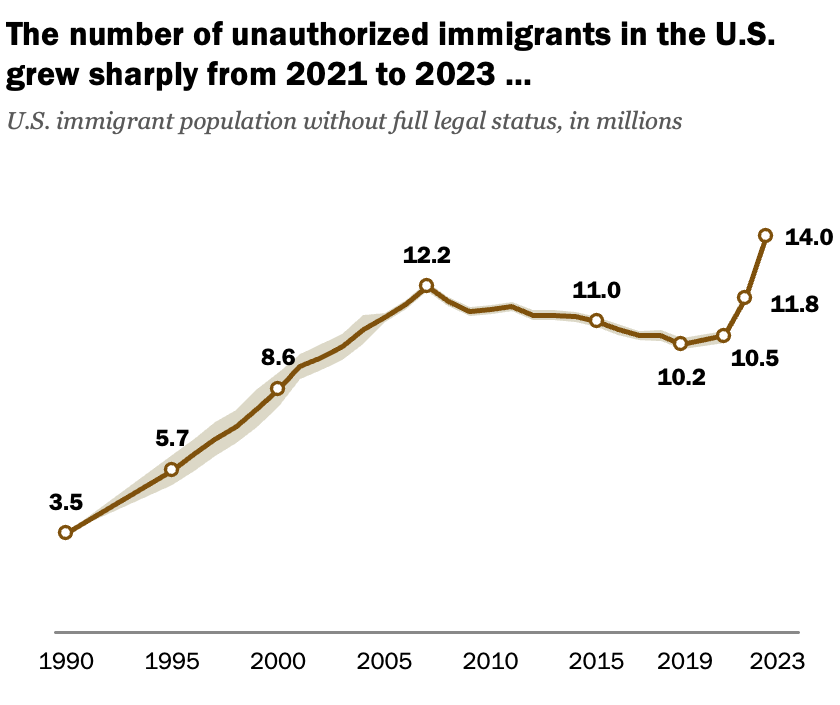

The most recent Democratic administration presided over an enormous surge in migration, with the unauthorized immigrant population exploding to 14 million in 2023 from 10.5 million in 2021 and likely millions more

…

Mr. Biden and his team asserted they couldn’t stop the surge without new legislation. That proved false: In 2024, having failed to get an immigration bill through Congress, Mr. Biden finally took executive actions to curb abuse of the asylum system and slow the flow of migrants across the southern border. When Mr. Trump took office, illegal border crossings slowed to a trickle. In other words, the problem had been fixable all along.

Is there a crisis?

I’ve learned that there is great disagreement over whether there’s even a problem here. Red says yes, of course’s there’s an immigration crisis. Blue says people only think that because of propaganda.

It’s certainly true that many more people started coming to America illegally in the Biden era:

This is millions of people who weren’t planned for, or selected on the basis of any coherent policy, all arriving within a few years. This has had many effects. As we’ll see below, cities often end up paying for temporary housing, medical care, and other essentials.

On the other hand, Trump has been hammering home a message about how immigration is bad for nearly ten years now, well before the recent surge. He was initially elected to “build the wall” and we had a “border crisis” in Trump’s first term despite declining numbers of unauthorized immigrants in the country. And his message has mostly been about crime and stealing jobs. So let’s get into that.

Immigrants and crime

Trump has publicly referred to immigrants as “criminals” hundreds of times. These statements sometimes specify that he means unauthorized immigrants, but sometimes not — appealing to anti-immigrant sentiment more generally.

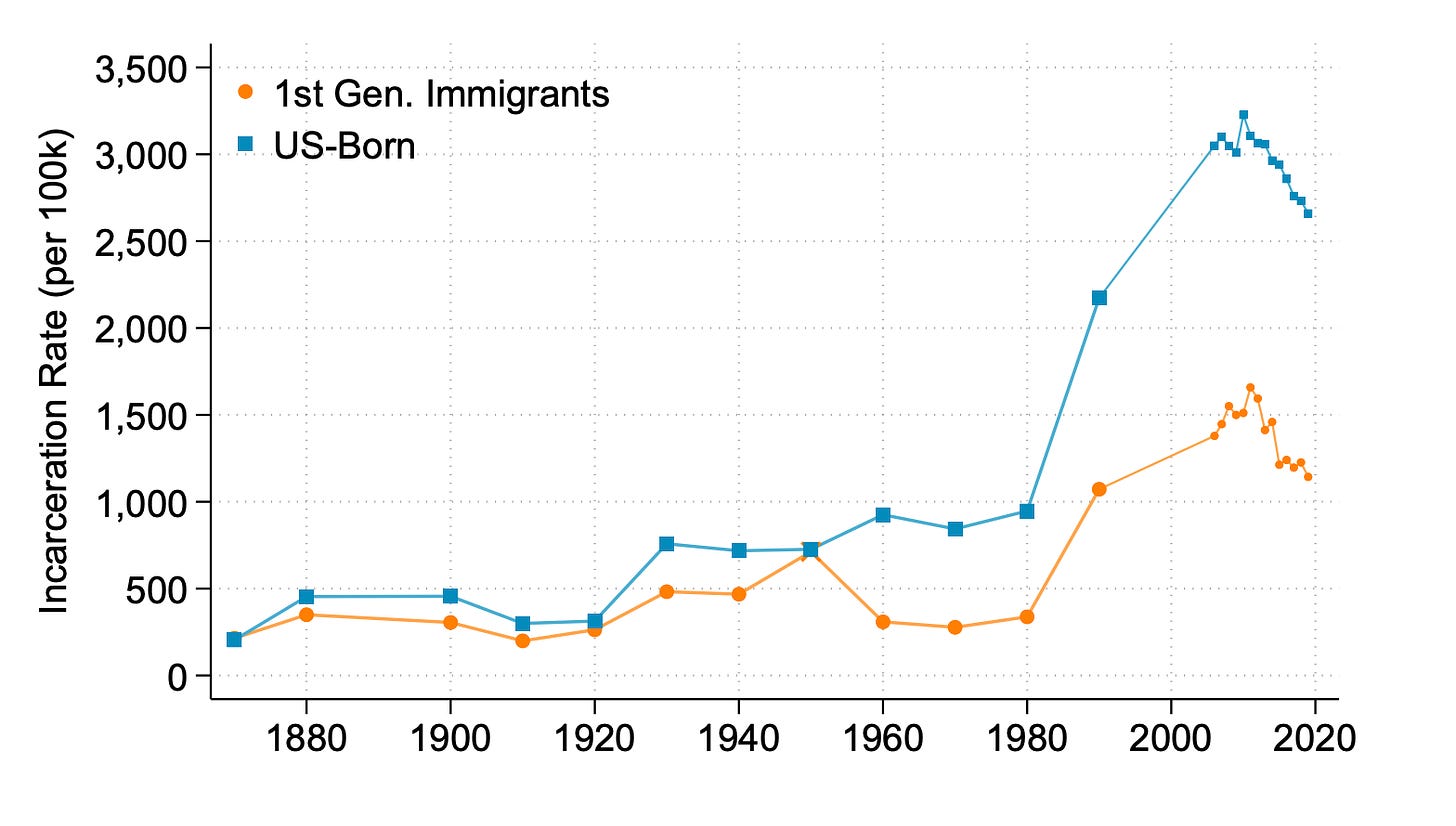

First things first: all the systematic evidence I could find suggests that immigrants (of whatever kind) have lower average crime rates. This seems to hold going back to at least 1870:

Maybe unauthorized immigrants are committing more crime though, since they’re already lawbreakers? Texas data says, no, they are arrested less often than authorized immigrants; but a Cato analysis says that nationwide, unauthorized immigrants are incarcerated at about double the rate of authorized immigrants. Everyone agrees that immigrants (of whatever kind) commit far fewer crimes than native-born Americans. This is so clear that even right-wing commentator Richard Hanania is angry that the government is lying about this.

On the other hand, there are definitely criminal groups in some immigrant communities. Latino gangs are not just a stereotype and MS-13 really is an international criminal organization, though it’s small in the US compared to domestic gangs. However, criminal groups have to be small fractions of all immigrants, because if they weren’t the average immigrant crime rate would be higher.

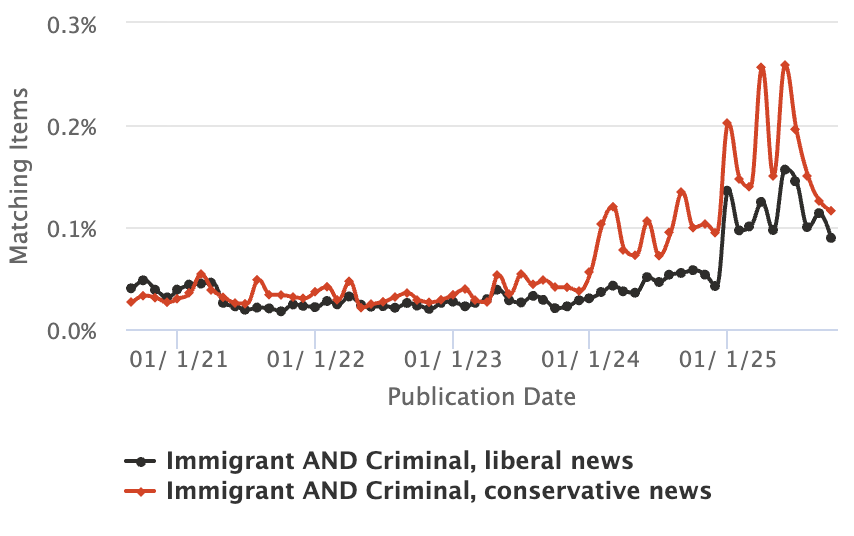

We are experiencing a narrative war over immigrants and crime. On one side, Trump frequently speaks of immigrants as criminals, and this association is definitely more common in Red media.

On the other side, Blue media has a tendency to underplay the race and/or nationality of criminals to try to avoid reinforcing this connection in the public mind. I don’t know of good examples in the US, but we’ve previously reported two European cases where the desire to downplay the involvement of immigrants led to a loss of trust in media and police (Berlin NYE assaults, grooming gangs). As we said then,

we are caught in a dysfunctional dynamic where the left justifies suppressing evidence because the right weaponizes it.

In any case, “removing criminals” was the campaign promise, and deporting unauthorized immigrants with a criminal record remains a popular policy (78% support). However, about a third of those detained by ICE have no criminal record.

The economics of immigration

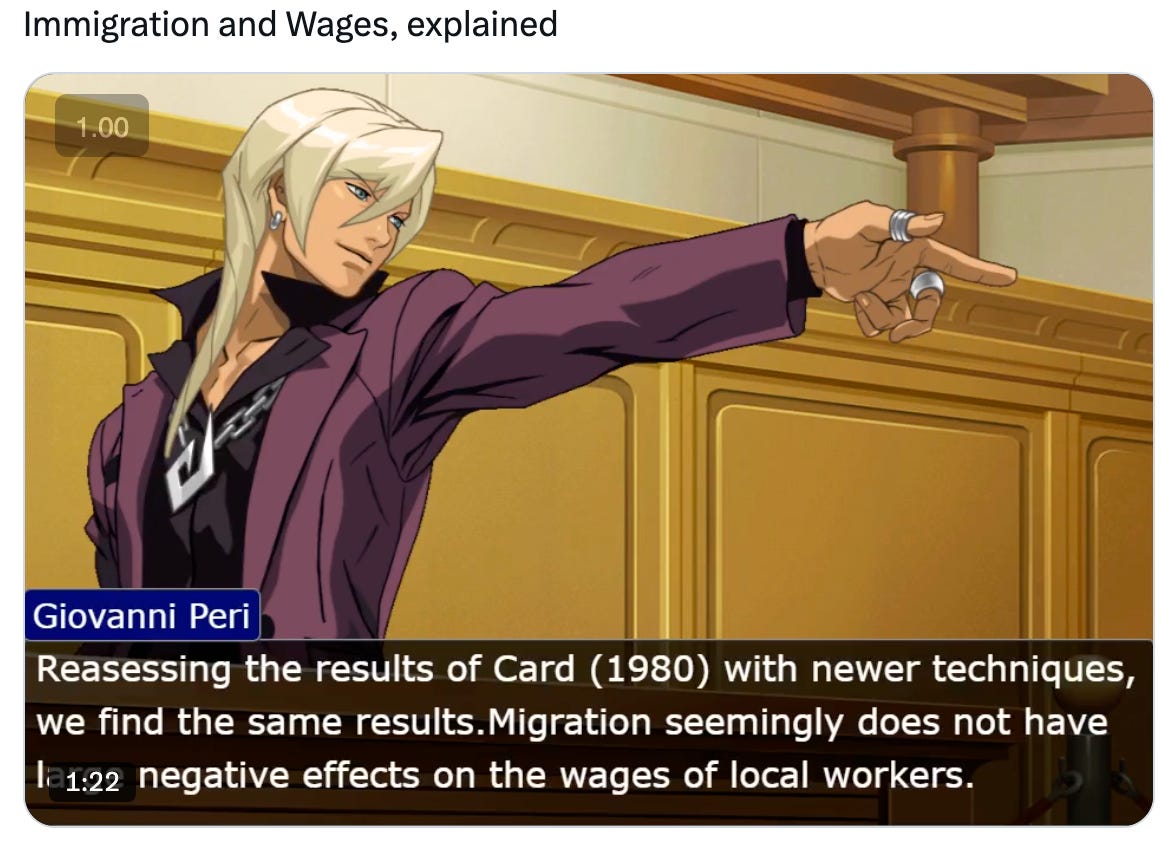

Do immigrants (of whatever kind) displace locals from jobs? I’m nowhere near qualified to referee this argument but Noah Smith might be, and he says immigration doesn’t push down wages. Immigrants compete for jobs, but they also buy things which expands the economy.

And to see why this is true, just think about babies. Each new generation is bigger than the one that came before it. If those young people were just a labor supply increase, then as population went up, wages would go down. But obviously that’s not what happens, because young people also buy stuff, which pushes up labor demand, which pushes wages back up.

Immigrants are just babies from elsewhere.

He goes through several decades of economics research on this point, and gets into questions about housing too. He is confident that this evidence will convince no one. (See also: Proof that the 2020 Election Wasn’t Stolen Which No One Will Read)

But this is not the whole story, just the macroeconomic picture. All of those new people have to go somewhere, and the situation on the ground can look different if lots of new foreign people are arriving in a particular place.

The recent wave of unauthorized immigrants put a lot of stress on local governments and schools. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that this “surge” cost state and local governments $9.2 billion in 2023 (that’s $19.3 billion in spending, offset by $10.1 billion more in taxes). New York City alone spent $3.75 billion in 2024. Those millions of new people all ended up somewhere, and needed housing, services, and education to survive. If you live in one of these places, you might have a very different perception of recent immigration trends.

The Cato Institute agrees that while immigration is good for the country as a whole, local governments pay a lot of the short term cost:

In general, the fiscal impacts of immigrants are positive at the federal level and negative at the state/local level compared with native-born Americans. Federal benefits are focused on the elderly, so the relatively young immigrant population receive fewer benefits compared with the third-plus generations.

The effect of immigration on wages follows a similar local pattern. It might reduce pay for some types of jobs in some area for some time, but net wages increase on average. Personally, the best discussion of the effects of immigration on wages I’ve ever seen is this anime courtroom fight between academics:

Xenophobia, racism, and culture

We need to talk openly about the fact that lots of people don’t particularly want more immigration, even law-abiding immigrants, even if it doesn’t hurt the economy. Even if all immigration to the US was legal, 30% of citizens would still want less of it, down from 55% last year. Again, immigrants have become more popular, not less, after Trump’s election.

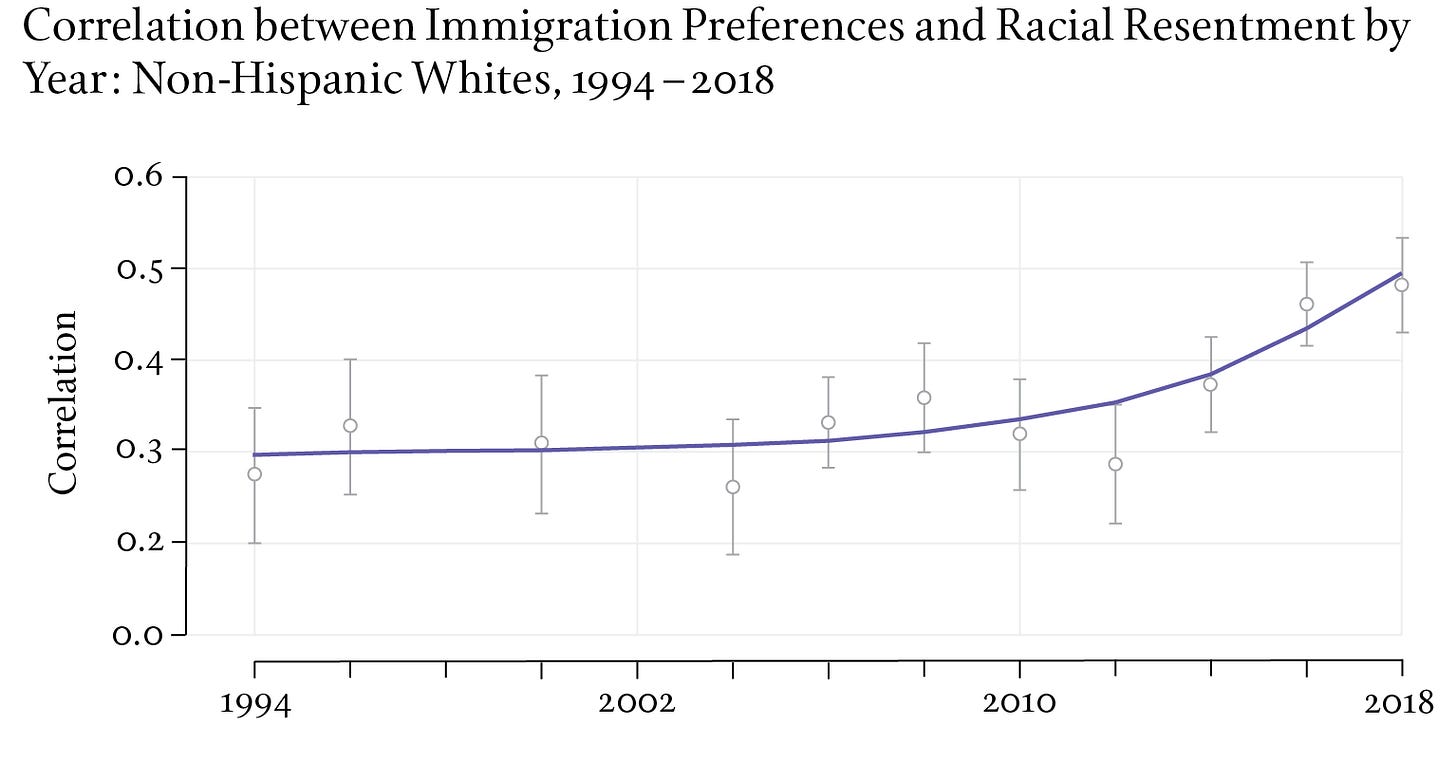

Still, a lot of people want less immigration — whether legal or illegal — and some of them feel very strongly about it. Do they simply not like immigrants? Or, you know, foreign people? Or maybe brown and black people? Unsurprisingly, this has been studied.

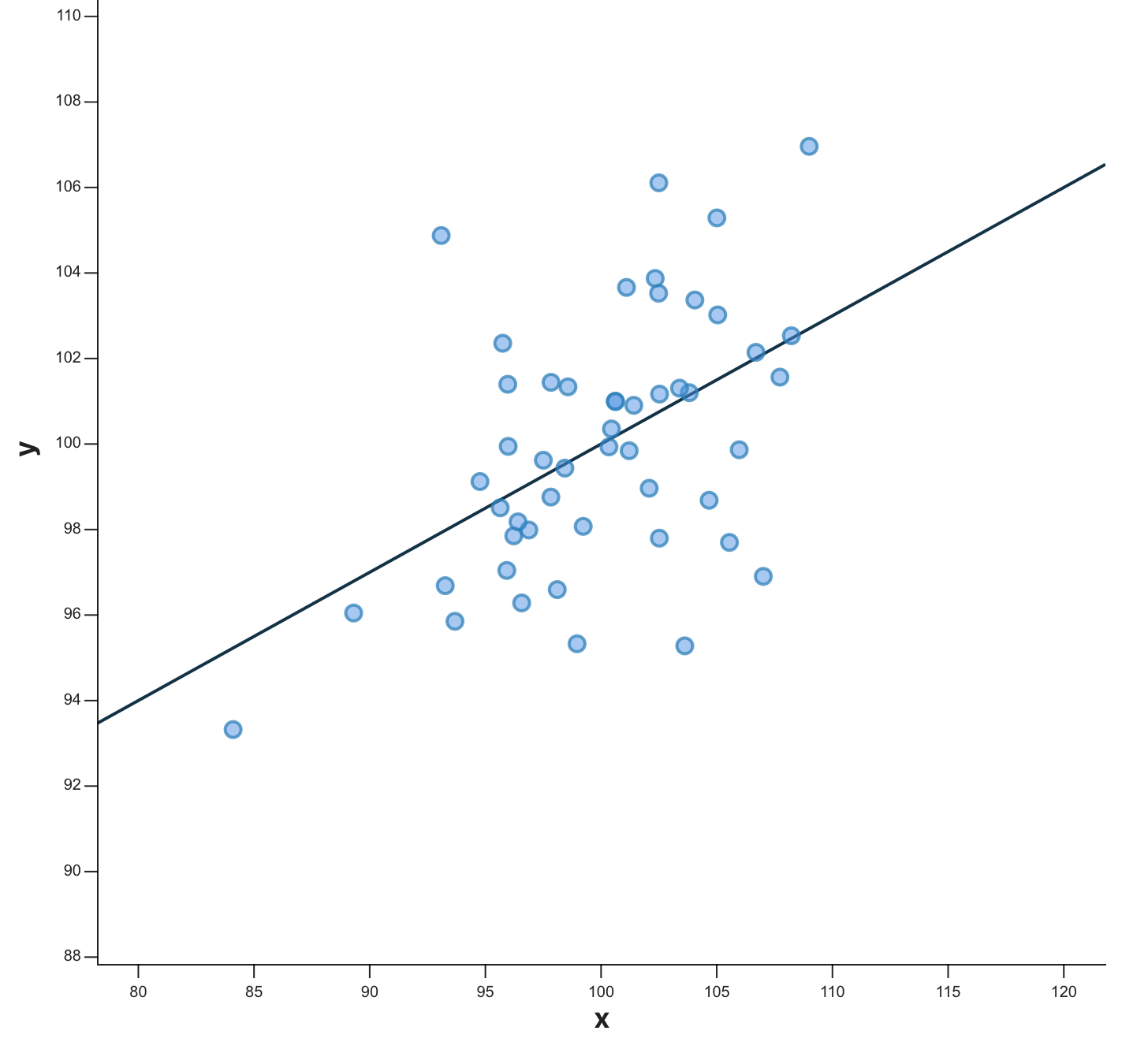

The individual-level correlation between “how many immigrants" and “how racist” has been increasing slowly over the past couple decades and currently stands at 0.5. Here’s what a plot with a correlation of 0.5 looks like:

So there’s a relationship, sure, but anti-immigration people have a pretty wide range of scores on “racial resentment” tests. There’s definitely racism involved in American immigration politics, and some of it is very ugly. But there are lots of people who want less immigration who aren’t particularly racist (and also lots of racist people who want more immigration).

Where does this opposition come from, if not crime, economics, or racism? Now we come to the nebulous zone of cultural opposition. People have widely different ideas of what American “culture” is, and varying degrees of attachment to it, but there’s no denying that a different culture is… different. The local diner is not in fact interchangeable with a taqueria. It’s not a matter of whether the taqueria is good or not, or even whether it’s better than that old diner. It’s a cultural change. If you like your own culture — which is a healthy and meaningful thing to do! — you’re going to mourn the loss of its places and its symbols.

The demographic future

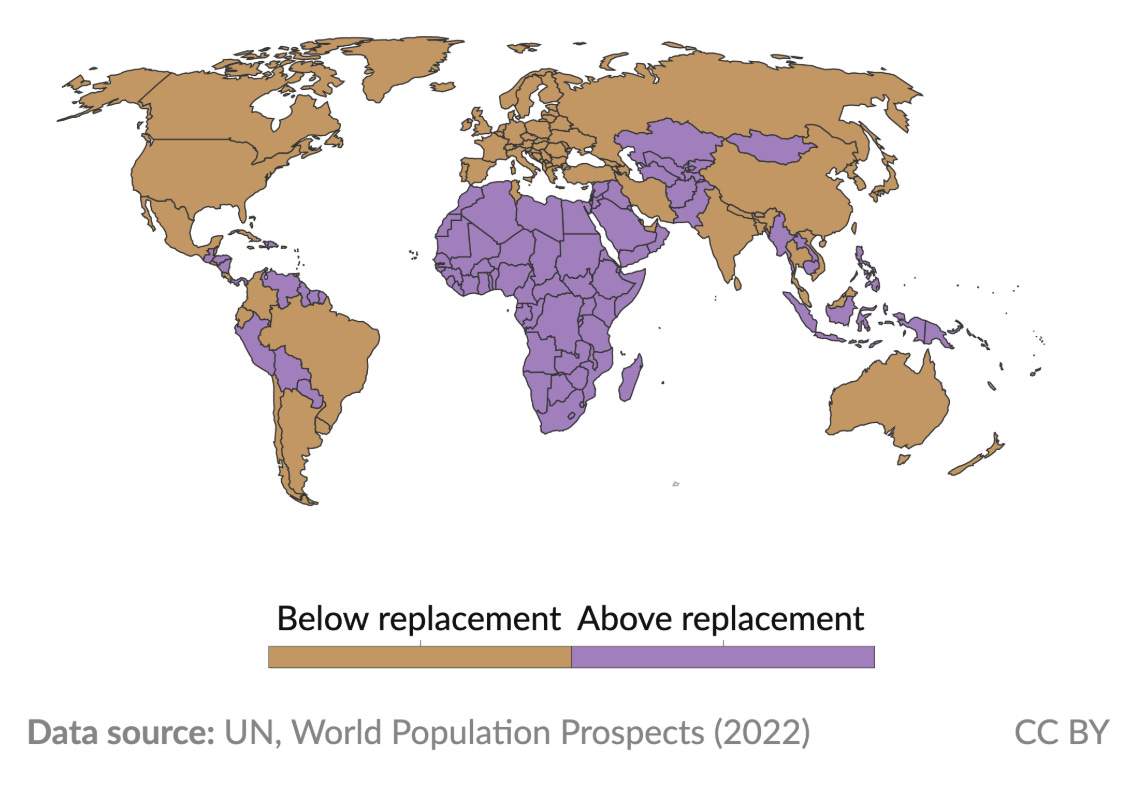

The thing is though, that change is coming eventually. Most developed countries are not having enough babies to replace their current population.

That means that if nothing changes, within a generation the population of these countries will start to decline. While many things encourage people to have more kids, none of them is likely to move the needle appreciably. That means the choice is either immigration or a shrinking population.

I know, I know, “great replacement theory,” but this isn’t some lefty plot to import lefty immigrants to win elections for Democrats. While Blue politicians have often publicly approved of the idea that changing demographics would benefit them, non-white voters have been steadily shifting to the right over the last decade plus. This flatly contradicts the idea of great replacement as an electoral strategy.

The simple fact is that if the population of America doesn’t decrease during the 21st century, then the percentage of foreign-born residents will necessarily increase. America could choose population decrease instead, but that would be choosing decline, and has its own serious problems.

Most developed countries are facing some version of this reality, and this will have cultural and political consequences that we are only beginning to grapple with. For some of the fastest shrinking countries, like Japan, the magnitude of the potential change is hard to get your head around, as Scott Alexander notes:

I understand why people don’t want to talk about the issue this way, because if you say demographic shift is a problem, people will call you a racist conspiracy theorist. I don’t think it’s racist to care about ethnic demographic shift - I think Japan as it currently exists is not completely interchangeable with a Japan made of 1/3 ethnic Japanese people and 2/3 ethnic Kenyans. But that’s probably not a discussion people can have openly given today’s climate.

Again, these changes will be slow — not decades but generations. Yet they are essentially unstoppable. And they are not evenly distributed. If you live in an American neighborhood or city that has been transformed by immigration in recent years, the long future is now.

There are big questions here. I believe it’s both possible and healthy to make cultural value judgements to guide the evolving character of a country, but this is no simple matter. This is the complicated future that looms in the background of any conversation about immigration. It’s unnerving, but also beautiful. This slow transformation is a deeply American story, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy.

What about the 14 million people already here?

Trump’s answer is to deport them. Although pre-election messaging may have been about deporting dangerous criminals, the White House now maintains that being in the country without authorization is itself a crime (true, it’s a Federal criminal misdemeanor) serious enough to warrant removal.

But the sheer logistics of actually removing all unauthorized immigrants makes it unlikely in reality. Even at the administration’s stated goal of 3,000 deportations per day, it would take a decade and a trillion dollars to forcibly remove all unauthorized immigrants in the US.

There’s an alternative. A large majority of Americans would much rather some sort of amnesty, that is, giving most unauthorized immigrants a way to stay legally.

Simultaneously, a slim majority of Americans support deportation for someone who is here illegally. This isn’t a contradiction: many people think both amnesty and deportation are better than the ambiguous status quo — essentially, they believe some immigration policy is better than no policy.

Democracy could mean less immigration

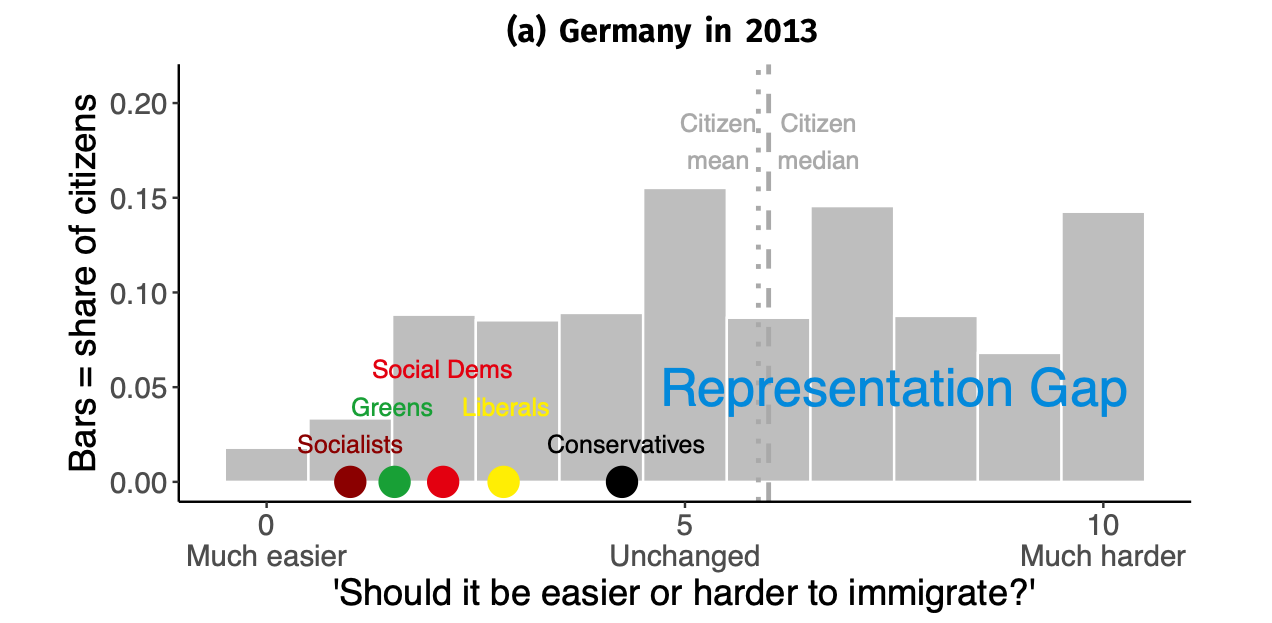

The rise of strongly anti-immigrant right-wing parties in the US and Europe has mostly been treated as an anomaly, some failure of democracy that begs an explanation. But a most provocative piece of recent research suggests that across Europe, this is just politicians coming into line with what their citizens always wanted. Here’s the distribution of views on immigration among German members of parliament from different parties vs. the broader population in 2013:

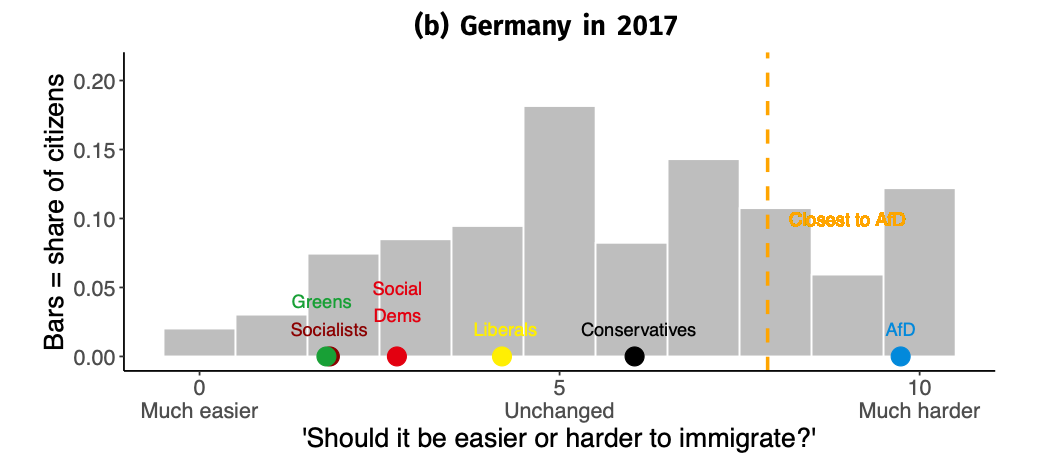

Note that even the “Conservative” party was to the left of the citizen mean. Now look at what happened five years later when the far right AfD party came onto the scene:

The introduction of the far-right AfD (“Alternative for Germany”) party caused the Conservative party to shift right to try to pick up people who would otherwise vote for AfD… and still the Conservatives actually ended up at about the mean citizen position (the orange dashed line is not the mean, it’s the dividing line between a Conservative voter and an AfD voter).

Matt Yglesias thinks something similar has happened in the US, and calls this the “boring theory of the populist right”:

Almost all theories in elite discourse about why people vote for right-wing populism posit that deindustrialization or free trade or “neoliberalism” or some other thing that left-wing intellectuals think is bad induces support for political parties on the right.

A simpler explanation is that a significant minority of the public in most Western countries agrees with right-wing cultural politics.

…

The problem is that while these right-wing views about immigration, crime, and gender roles are not per se illiberal, you can see why they disproportionately appeal to people with illiberal views and authoritarian mindsets. If all the elites who favor democratic institutions also refuse to supply the policy options on immigration and crime that the voters want, then voters will ultimately get those policies from more sinister types.

H.L. Mencken once said, “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” Dan Williams has suggested that maybe what we’re seeing is democracies getting what they want, for better or worse.

A way through

It seems like there might be a policy combination that could satisfy most people: strong immigration enforcement combined with a path to citizenship.

Enforcement is necessary because otherwise immigration policy is only paper, and cannot shape the reality on the ground. We can have democratic debates about the right kind and amount of immigration, but those choices are meaningless if nothing stops people from coming here on their own.

At the same time, mass deportation is not only cruel but unnecessary. Unauthorized immigrants are mostly working jobs (like growing our food) and paying taxes, and are more law-abiding than the native born. Immigrants are more popular than ever with Americans, and a pathway to citizenship is polling at 78 percent!

But this is just my best guess. What I want more than anything is a way forward that doesn’t get more people separated from their families, more people caught up in ugly resentments, more people hurt or killed. I’ll take any path that leads us there.

Quote of the Week

You often hear voices on the left urging it to “make the positive case for immigration”. By that they generally mean, “Remind voters of the many ways in which immigrants enrich our country, economically and culturally, while denouncing bigotry”. It’s not that this case isn’t right - I believe it - but it’s an old tune that voters find it easy to ignore. More fundamentally, it doesn’t address why fair-minded, tolerant voters might worry about immigration in the first place. It just tells them they’re wrong to.

This hit me deep, Jonathan. Especially your line about this being a “deeply American story… unnerving, but also beautiful.” I came here at 11 as an assylym refugee. For people like me, immigration isn’t an issue; it’s a memory. What I’ve learned is that America’s conflict with immigration isn’t just political, it’s emotional. It’s about the gap between the country we say we are and the one we actually choose to be. Im still trying to process this current climate we are on. See below. ANyways, thanks for writing this. The data points alone was great.

https://open.substack.com/pub/pesosandpixels/p/you-told-us-to-come?r=3etobz&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web