Red is Divided Over LGBTQ+ Issues – BCB #58

Also: Should we assume people act in good faith? and a new book on the behavioral economics of polarization

Trans issues reveal rifts in Red LGBTQ+ support

During Pride Month, Fox Corp.’s internal employee site read, “The contributions and impacts of members of the LGBTQ+ community … deserve to be celebrated and uplifted,” and linked to various supporting resources including suggested books to read to “expand your perspective.” Right-wing commentator Matt Walsh (of “What Is A Woman” fame) took to Twitter to express his disapproval.

This latest sign of internal rifts raises the question: where does Red actually stand on LGBTQ+ issues?

Generally, we’ve seen increasing support for gay marriage among all Americans (Red, Blue, and other) over the last 20 years. Yet there’s been a sudden drop among Republicans, from an all-time high of 56% in 2021 to 41% in 2022.

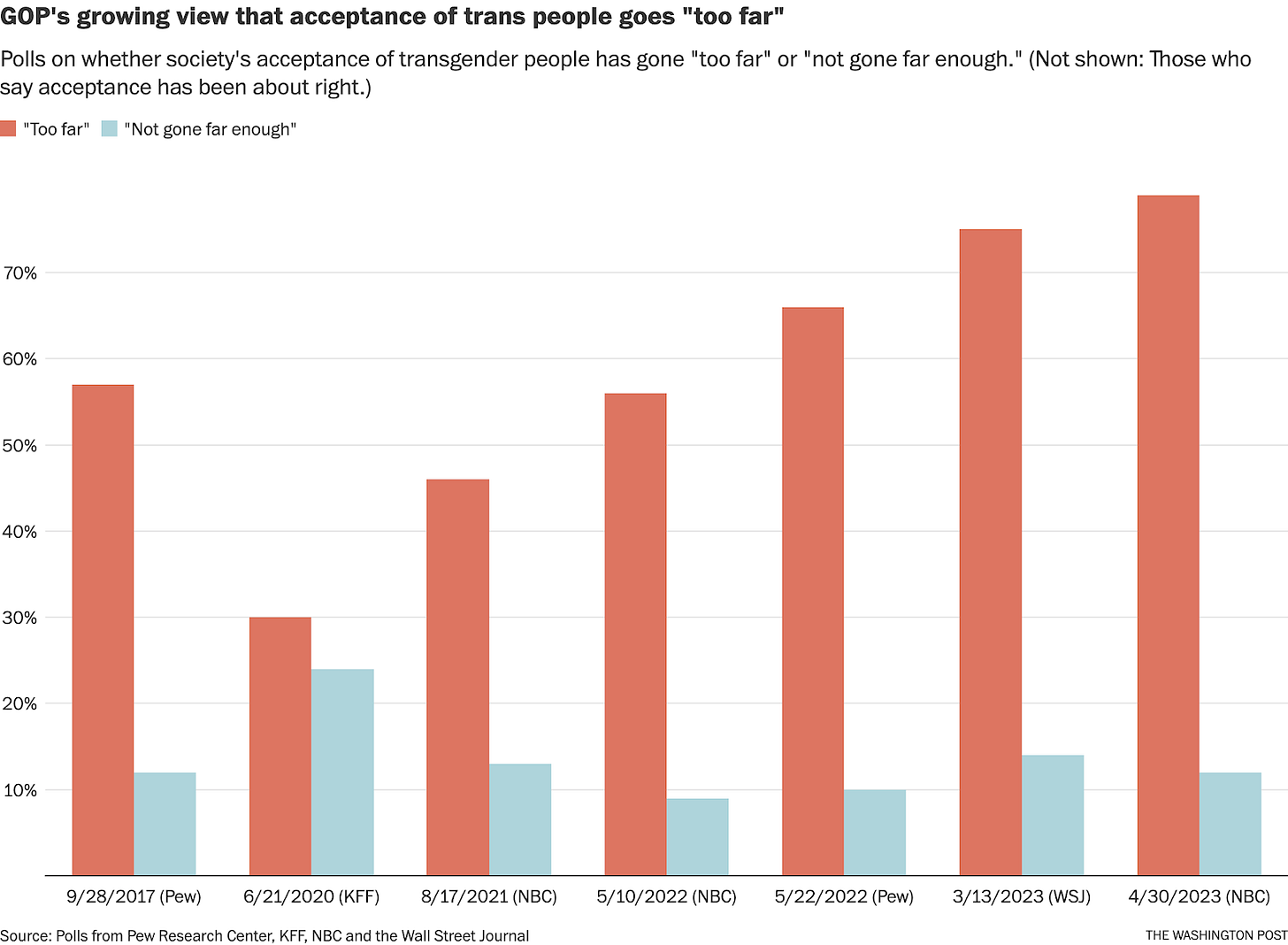

This dip might be due to the increasing association of gay marriage with transgender issues. The Wall Street Journal analyzed several polls and found a significant majority of Republicans now believe “acceptance of trans people goes too far,” with opposition rising from 30% in 2020 to 79% in 2023.

Putting this all together, the story seems to be that while Red is generally becoming more accepting of homosexuality, it’s actually becoming less accepting of transgenderism. But not universally, as Fox’s support shows. Red isn’t a monolith, and neither are LGBTQ+ people.

Should we assume people act in good faith?

Tilt too far on either side of the tightrope of trust, and you can tumble into naivety or cynicism. Economist Arnold Kling suggests that biasing towards “assuming positive motivation” is the better choice.

Assume Positive Motivation does not mean that you have to say that both sides are equally valid. You can still believe that your side of an issue is 100 right and the other side is 100 percent wrong. What you have to let go of is the belief that the other side is evil.

Unfortunately, characterizing the other side as evil often garners significant support, as seen with former primetime host Tucker Carlson and news headlines that use anger and fear. Yet Kling believes that the survival of our nation's unity largely depends on widespread application of “Assume Positive Motivation.” It’s certainly an essential step in clarifying misunderstandings and rebuilding trust.

But there’s also a line of argument that one shouldn’t assume good intent. Annalee, a community safety and code of conduct consultant, questions if assuming good intent is truly a useful ethos in the face of repeated injustices. It could potentially cause harm if applied without considering those who might misuse it, and unintentionally undermine people’s real experiences.

You need to address the system of behavior that makes marginalized people feel unwelcome, rather than treating each instance of that behavior as a personal conflict that has occurred in isolation … Telling people to “assume good intent” is a sign that if they come to you with a concern, you will minimize their feelings, police their reactions, and question their perceptions … [It] sounds like they’re really telling you to shut up.

Annalee proposes a systemic approach that recognizes and addresses the harm caused, emphasizing victims’ feelings over offenders’ intentions. This centering of feelings is, of course, a frequent Red objection. And it’s certainly true that victimhood can be exploited – and yet, centering intentions and ignoring effects isn’t a plausible strategy either.

We see a balance here. Trust works when it’s paired with security, which allows us to be both open and protected. Too much trust can leave us exposed, while excessive skepticism can prevent meaningful communication and collaboration.

A new book on the behavioral economics of US polarization

When Daniel Stone was writing his new book, UNDUE HATE: A Behavioral Economic Analysis of Hostile Polarization in US Politics and Beyond, his editor encouraged him to be less provocative. As a polarization researcher and associate professor of economics at Bowdoin College, he needed to steer clear of his biases to remain non-partisan. After all, his intention was to explain how negative ideas about the other can escalate conflict:

My book argues that intergroup conflict is often driven by false beliefs about out-groups in the same way that conflict within groups is often driven by misperceptions individuals hold about one another … conflict in general is often driven by misunderstanding.

For Stone, affective polarization is the country’s most significant issue. “It causes so many other problems and prevents us from solving other problems, and even threatens democracy.”

His book proposes solutions to bridge deep divisions, including bringing opposing sides together for meaningful “real world contact.” He emphasizes that these interactions are more successful if the environment is non-competitive and constructive.

Stone has put this into practice with his online project, Media Trades, a simple site that enables individuals on the Left and Right in the United States to exchange news articles on polarizing issues. When implemented into his 2021 university curriculum, 70% of the 123 participating students showed an interest in diversifying their news.

Stone also noted that five students said they opened up to the other side. In his classroom, Stone witnessed the contact hypothesis in action—people’s hostility decreasing as they engage with diverse ethnic, religious, and political groups.

Quote of the Week

As a rule of thumb: cut your hate in half. (I'm not saying "don't hate" - but don't hate as much as your instincts tell you to, or at least try to hate with intellectual humility).