Knowing Politicians’ Personal Lives May Reduce Polarization – BCB #59

Also: can you argue the other side of affirmative action? and why having too many aspiring elites could make conflict worse.

Knowing politicians’ personal lives may reduce polarization

Political candidates gain popularity when they share personal details, especially among people who identify with the opposite party, according to this new study. That is, sharing humanizing information is depolarizing.

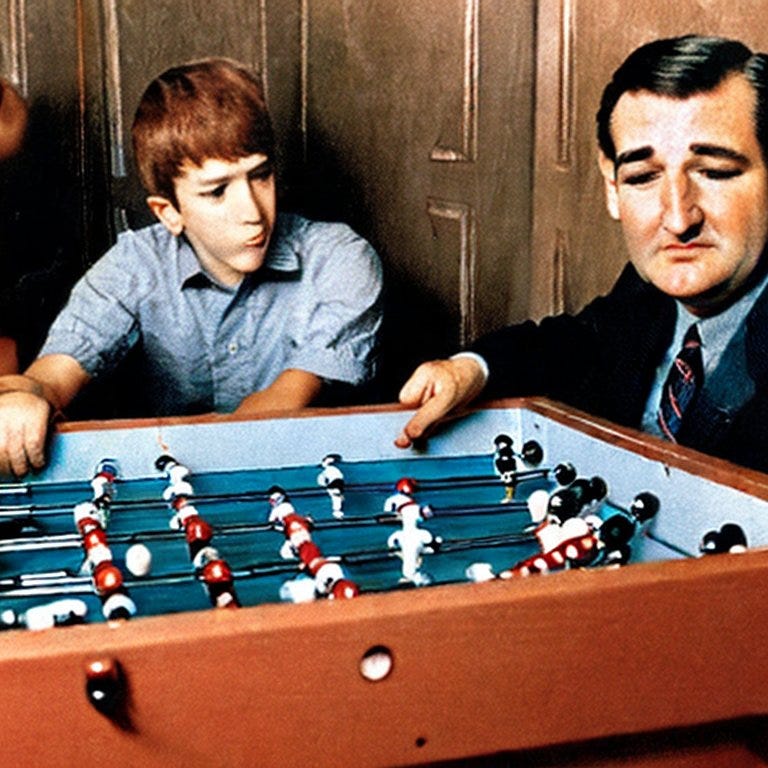

Researcher Jennifer Wolak compared reactions between people in a control group who were given only a senator’s party and state they represent, versus a group who were also given nonpolitical personal details about the candidates. For example, this sort of information about Ted Cruz:

I was once suspended in high school for skipping class to play foosball.

As a kid, I used to go bull-frogging on the lake behind our house.

My favorite movie is The Princess Bride. I can quote every line.

Individuals who read the senator’s personal details tend to express warmer sentiments compared to those who did not.

When an individual is described as a “politician,” people tend to interpret information through existing negative preconceptions of politicians. However, if the same individual is described in a way that invites people to think of him or her as a “person” rather than a “politician,” they offer warmer evaluations.

Naturally, partisanship still matters; it has a much larger effect on perception than humanizing details.

A humanizing political campaign strategy might help improve people’s perceptions of out-party candidates, offering a possible exit from ossified partisan voting patterns — patterns that can lead people to elect horrible candidates merely because they perceive the other side as worse.

Can you argue the other side of the affirmative action debate?

Affirmative action is one of those divisive topics where each side argues with a different moral logic, and often completely fails to understand the other. Tangle recently summarized reactions to the recent Supreme Court ruling (we previously interviewed founder Isaac Saul about his approach to journalism). This provides a handy list of the core arguments; we can disagree about what matters, but we should at least understand what our opponents are trying to say.

On the Blue side,

Many criticize the ruling, saying it upends decades of precedent and will harm Black and minority students.

Some suggest the majority’s legal reasoning is embarrassing and ignores the clear original intent of the 14th Amendment.

Others argue that affirmative action was a broken policy, and that prior legal rulings ultimately doomed it.

On the Red side,

Many support the decision, arguing that the court has reinforced the idea race should never be used to discriminate.

Some suggest that colleges can move to economic-based affirmative action if they want more diverse campuses.

Others argue that the dissent in the opinion ignores the plain meaning of the 14th amendment, instead embracing the idea that two wrongs can make a right.

Interestingly, there seems to be support on both sides for wealth or needs-based admissions. A New York Post article expands on the possibility:

After California outlawed race-based affirmative action in 1996, UCLA Law School implemented a wealth-conscious admissions process. Analysis of their admissions data revealed that Hispanic students were twice as likely to be accepted and Black students eleven times as likely as they otherwise would have been.

The crux of the disagreement is that Blue believes society must use every means at its disposal to address racial inequality brought by America’s racist history, while Red believes that certain means are justified but not affirmative action, as it prioritizes an abstract idea of race over the unique situation of each individual.

The irony is that each side is calling the other racist. Red thinks it's racist to choose based on race. Blue thinks it's racist to assume minorities get the same access to opportunity. Both sides are protecting their values, and both of those values involve equality.

Intra-elite competition and the culture war

In his new book, End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites and the Path of Political Disintegration social scientist Peter Turchin analyzes dozens of factors contributing to the fall of historical societies, such as population, well-being, and governance. He identifies two main causes of instability:

The first is immiseration–when the economic fortunes of broad swaths of a population decline. The second, and more significant, is elite overproduction–when a society produces too many supperich and ultra-educated people, and not enough elite positions to satisfy their ambitions.

Many people have investigated the link between economic inequality and polarization, generally finding that they’re correlated. Turchin adds the element of intra-elite competition, likening it to playing a game of musical chairs.

The wealthy have become wealthier, while the incomes and wages of the median American family have stagnated. As a result, our social pyramid has become top-heavy. At the same time, the U.S. began overproducing graduates with advanced degrees. More and more people aspiring to positions of power began fighting over a relatively fixed number of spots. The competition among them has corroded the social norms and institutions that govern society.

Turchin identifies ideological disunity among the elites as a key feature of pre-crisis periods, as seen in America just before the Civil War. He believes there may be hope to persuade the ruling elites toward reforming the current system that siphons wealth away from the rest of society, but this depends on the willingness of the elites to sacrifice their short-term interests for long-term collective ones.

Alexander Beiner brings out the economic argument more explicitly:

Turchin draws on an extensive body of evidence to point out how real wages among working class people in the U.S. have declined since the 1970’s, and less educated workers’ skills “were less in demand in the new economy” and they also “experienced stronger competition from immigrants, automation, and offshoring than college-educated workers did.”

Beiner further expands on Turchin’s argument by observing that elite values, such identity politics, are often rejected as they filter down the socio-economic ladder. We explored something similar in previous issues on Red rural resentment and the politics of the working class. He hypothesizes that this opposition is driven by the disparate socio-economic conditions across America.

Quote of the Week

Competition is healthy for society, in moderation. But the competition we are witnessing among America’s elites has been anything but moderate. It has created very few winners and masses of resentful losers. It has brought out the dark side of meritocracy, encouraging rule-breaking instead of hard work. All of this has left us with a large and growing class of frustrated elite aspirants, and a large and growing class of workers who can’t make better lives for themselves.