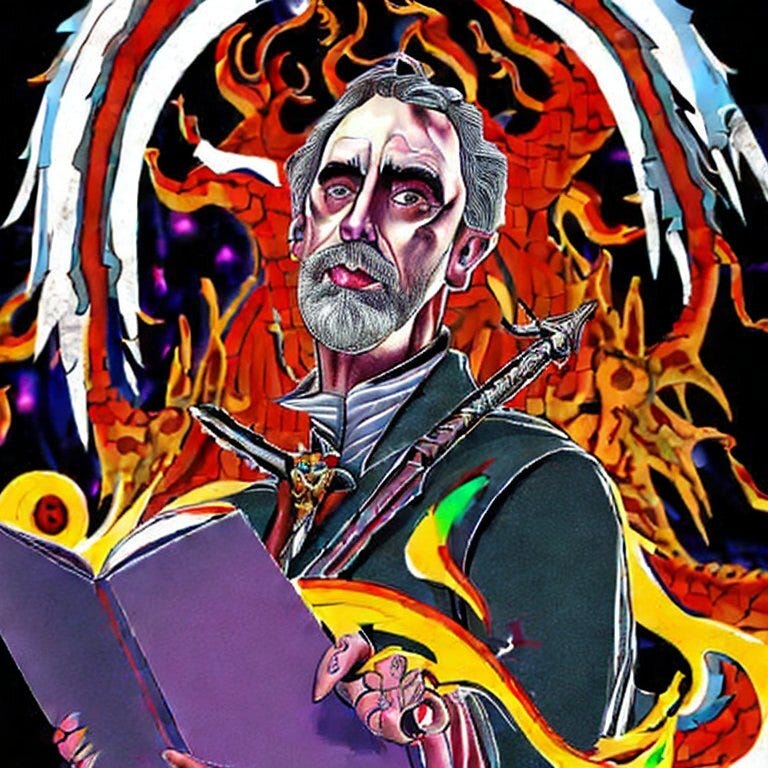

Jordan Peterson used to be a Peacemaker – BCB #51

Today he's a culture warrior, but underneath there's a careful understanding of the nature of conflict.

You probably know Jordan Peterson as a Red firebrand, but you probably don’t know that the Canadian psychologist’s early work involved bridging ideological divides and seeking common ground. Suspended Reason has written a fascinating history of what Peterson used to be, and what he is now. This is the story of how he got tangled up in the culture war, sucked into the sensationalism of social media and the pressures of polarization.

In 2006, Peterson wrote an essay called “Peacemaking Among Higher Order Primates.” The 44-year-old Peterson who wrote this treatise showed remarkable insight about the subjective nature of truth, its relation to conflict, and the difficult role of the mediator:

Facts are facts. Opinions about the facts differ. It is therefore the job of the peacemaker to bridge the gap between opinions, and in that manner, bring about reconciliation. This much seems obvious. But what if the facts themselves differ? What is if the basis for the disagreement is so profound that the world arrays itself differently for each antagonist – and worse: what if the disagreement extends beyond the antagonist, to these peacemaker, who sees the facts themselves in a manner that neither antagonist can accept? What then?

Peterson was inspired by some of the most notable thinkers of the 19th and 20th centuries, including philosophers like William James, Frederich Nietzsche, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, and sociologists Ervin Goffman and Pierre Bourdieu. All of them believed that “facts” were not just waiting to be discovered in the observable world; rather, “facts” come about for pragmatic reasons, as our selection and emphasis of certain facts can reflect our goals and agendas. In other words, to state a fact is to simultaneously make a value judgment about what is important. The sum total of these so-called facts, or what Peterson calls “pragmatic patterns,” creates a map that helps us navigate in the world – a worldview.

Working from this framework, Peterson saw peacemaking as being about mediating individuals’ disagreements about facts:

But the facts do differ [between people], because the world is complex beyond the scope of any one interpretation. For this reason, there can be disagreement about first principles, as well as their derivatives. This means that the job of the peacemaker is to establish an accord that allows the facts themselves to become a matter of agreement.

The problem, according to Peterson, is that we can never access the full truth, because we are limited in our time and space to the “local.” Therefore, a mediator should be open-minded and avoid moral certainty, because there will always be a “landscape of conflicting interpretations,” where diverse partial truths exist. Peacemakers must bridge gaps to reach a higher level of truth, combining local truths and perspectives and learning from each party to reach a “global victory” of broader agreements. This imagined process is strikingly similar to conflict transformation, where we envision peace as an evolving, continual effort.

If this seems very different from the Peterson you know today, it is. In the late 2010s, he seemed to shift his focus to short-term local victories. In a way, he became the villain he warned us about.

David Fuller, who was once an ardent supporter of Peterson – he even directed a documentary about the man – last year described Peterson’s descent into conflict. Today Perterson is a “one-man lightning rod for the culture war, a catalyst and recipient of an immense amount of cultural energy, analysis, projections and much more.” Yet he once drew on various fields such as neuroscience, psychology, mythology, and psychoanalysis to deliver balanced perspectives. Fuller writes,

It's increasingly hard to remember the first wave of Peterson, when he was arguing how we needed both the left and the right, and made criticisms of both, while arguing an essentially synthesis position. Over time he started taking sides in the war more and more fiercely.

…

My view is that there were always multiple different Petersons cohabiting at the same time, the thoughtful scholar and the academic alongside the reactive political culture warrior. I was definitely selective in seeing the best version of him. Over time the latter became more and more rewarded and prominent until it became the dominant persona. How and why that has happened, to Peterson and to many other public intellectuals, is one of the major problems of our social media age

There’s an important thread in Fuller’s analysis: Peterson became a major media figure, and polarized media makes merciless demands on its creators. Last year Peterson joined the Daily Wire, a firmly Red news and media website run by the controversial Ben Shapiro. He often uses Twitter to express his outrage and to provoke, as when he called a plus-sized model “not beautiful,” referring to the idea that she was as “authoritarian tolerance,” before proceeding to rage-quit Twitter. Peterson himself blames social media platforms for his polarizing behavior, calling them a “pollution of the domain of public discourse.” After taking a hiatus from Twitter, he stated, “I started using it again, a few days ago, and I would say that my life got worse again almost instantly.”

Helen Lewis describes it this way in What Happened to Jordan Peterson,

[Peterson] gazed into the culture-war abyss, and the abyss stared right back at him. He is every one of us who couldn’t resist that pointless Facebook argument, who felt the sugar rush of the self-righteous Twitter dunk, who exulted in the defeat of an opposing political tribe, or even an adjacent portion of our own. That kind of unhealthy behavior, furiously lashing out while knowing that counterattacks will follow, is a very modern form of self-harm.

Even today, Peterson has his depolarizing moments. He invites people across the ideological spectrum onto his podcast, including Muslims, Black activists, and famous feminists. It should be noted, however, that his guests usually share some common ground with him on key issues. Some critics argue that his guest selections are a form of tokenism, inviting someone who would usually disagree with him to show why Peterson is ultimately right – but at least he’s not talking to himself. Perhaps there’s a hint of his old ideals here. And if you’re among the many, many people who associate Jordan Peterson with vile things, it’s quite likely you’ve never actually read what he’s written. You may be surprised at how reasonable he often is.

Yet warped by the incentives of culture war media, Peterson no longer fits the description of the careful peacemaker that he penned decades ago. Instead, he more often resembles a conflict entrepreneur: someone who profits from the promotion of outrage and division.

Quote of the Week

For the facts to come into alignment, the antagonists must want something that transcends the local – even the local victory. They must want peace, more than dominance. They must want peace, more than success. They must want peace, more than security, more than charisma. That means that the peacemaker must be able to sell them something more valuable than victory, more valuable than success. That means the peacemaker must know what it is, that is more valuable than victory.

"And if you’re among the many, many people who associate Jordan Peterson with vile things, it’s quite likely you’ve never actually read what he’s written. You may be surprised at how reasonable he often is. "

Indeed. I'm one of those people who first heard of him because of the culture wars.

But I have a young cousin in India in his early 30s who reads Peterson almost exclusively as a self help author. He has some idea that Peterson is controversial in the American culture wars but that's it. It's been interesting to me the facets of Peterson's writings (commonsensical, noon controversial) he emphasizes.