Is It a Problem If a Newsroom Serves Only One Side? – BCB #98

It takes specific action to avoid a lopsided audience.

Several weeks ago, NPR senior editor Uri Berliner published an essay criticizing the news station for losing the public’s trust as its agenda grew more progressive, which set off a chain reaction of online conversations and counter-essays. Whatever your view of the recent blow-up, one fact stands out: NPR has lost a large portion of its Red audience, and some of its “middle of the road” listeners, too.

Berliner’s essay included numbers on NPR’s changing audience; NPR reprimanded him for publishing this “confidential” information, but did not dispute its accuracy.

Rather than getting into the weeds about whether NPR is biased (and how one would even determine that) we’re interested in a more fundamental issue: is it a problem for an outlet like NPR to have an audience that strongly leans one way? And if it is, how could a newsroom keep—and serve—a politically diverse audience?

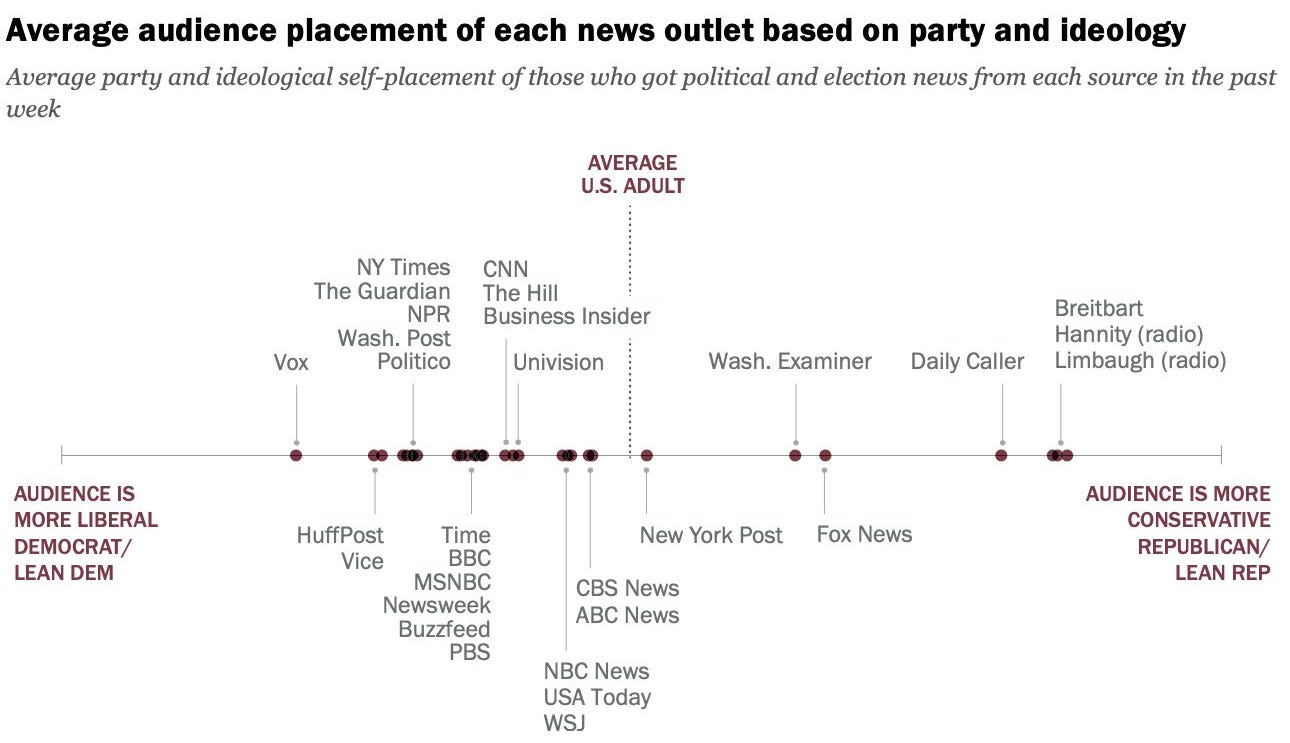

These have become pressing questions because news audiences are rapidly polarizing. Very few news outlets now have significant numbers of Red and Blue readers.

It’s reasonable to say that not all news organizations need an ideologically diverse readership, but we believe at least some should have one. On this, Berliner and NPR CEO Katherine Maher may agree. They both allude to NPR’s “public” name and mission, suggesting that perhaps the organization ought to make efforts to serve a wider audience than other news outlets. But if having a bipartisan audience is a goal, news organizations need to take intentional, specific actions to build broad trust. We’ve collected some tips below.

News audiences have become divided

It’s no secret that many mainstream media organizations have an audience that skews Blue. Pew Research found that most of the major outlets’ audiences fall at least slightly to the left of the average U.S. adult.

It’s hard to say how much audience polarization has changed over time. We wish we had those numbers, but we don’t—that’s part of why Berliner’s NPR numbers are so interesting. However, other data suggests that audiences have diverged significantly over the last two decades. For example, people tend to prefer ideologically aligned news, and it’s clear that news content has become more polarized.

A National Bureau of Economic Research working paper estimates that three popular cable news channels—Fox News (FNC), CNN and MSNBC—all became more partisan in their ideologies between 1998 and 2012. By comparing the language the channels used to language Congresspeople used, the researchers concluded that during this time, Fox News became much more Red, CNN became somewhat more Blue, and MSNBC became much more Blue. (This will surprise no one, but it’s always good to check intuitions with data.) The Economist updated this language-based analysis with more recent data and found similar results.

The politics of journalists have changed over time as well. While the proportion of journalists who self-identify as Democrats remained steady from 2002 to 2022 at 36%, the proportion who identify as Republican shrunk from 18% to 3% (many more journalists now say they are “independent”). Journalists have been unrepresentative of American voter demographics for decades, and the disparity is now quite stark. A 2020 study estimated ideology by analyzing who journalists follow on Twitter, finding that nearly 80% are to the left of the average user.

Conversely, we expect that journalists at, say, Fox News would be considerably Redder than the average—that’s probably the bump at the right of the figure above. It seems likely that audiences will care about newsroom demographics. Similarly, should newsrooms that want a bipartisan audience care if they don’t have a bipartisan staff? And if they don’t have people from one side in the newsroom, what are the forces keeping them out?

Whatever your answers, all of this data paints a picture of news organizations drifting apart politically over the last 20 years, in terms of both audiences and staff.

How to keep a bipartisan audience

The trends over the last two decades make it clear that news organizations must be intentional about reaching a politically diverse audience, if that’s a priority.

We’ve previously covered one organization that is succeeding at this. Roughly 40% of Tangle News readers self-identify as liberal, 30% self-identify as conservative and the rest say they are independent or outside the left-right binary. This takes specific work. When founder Isaac Saul learned that people were unsubscribing after picking up on what they considered biased language, he updated the newsroom’s style guide to be as “ideologically neutral as possible.” This meant changing how they write about race, immigration, transgender healthcare, COVID-19, abortion and more.

Saul described the motivation for these changes like this:

Before they even got to the arguments, they were reading something that pissed them off for one reason or another and they decided that they had spotted bias. There was a cue somewhere that this outlet is biased and we weren’t fulfilling our promise. And so they were done, they didn’t want to support us anymore and they unsubscribed … We want to get to our goal. We want to get people out of [the introduction] without having them feel their spidey senses are going off about some kind of political bias. How can we do that? We can change our language in ways that we think both sides will understand and view as acceptable.

Saul has said he received very positive feedback after the change, with many readers thanking him for explaining the reasoning behind the changes, even when they disagreed with them.

Transparency is also a key value for Trusting News, a non-profit founded by Joy Mayer, which believes that “in a world in which news consumers are confused and exhausted by information, responsible journalists should be transparent and proactive about why they are worthy of trust.”

The group offers step-by-step guides for journalists and has a thorough database of trust-building initiatives led by newsrooms. They have even come up with an “Anti-Polarization Checklist” to help journalists think through audience perceptions at each stage of the reporting process. Mayer writes:

News consumers make assumptions about journalists’ own values through the way stories are framed, sourced and written. In some cases, journalists are communicating where they’re coming from purposefully and transparently. But in others, their views and assumptions are creeping in without intention. And coverage that feels accurate and consistent with how they see the world actually communicates a political agenda to some news consumers.

On the checklist itself, Trusting News explains:

The goal of the checklist is NOT to make all content palatable to all people, or to remove the journalist’s authority or judgment. Rather, it is designed to make room in the editing process for journalists to be intentional about: examining how their story might be perceived by people with different values and experiences, identifying what they are communicating to their audience intentionally or unintentionally about how they see an issue (and) considering including enhanced transparency about their goals and process.

The NPR situation is complicated, and frankly, we’re not going to wade into trying to decide who is right. But it’s interesting to note that since Berliner’s essay, NPR has announced that it will hold monthly meetings to review coverage and tackle some of these questions. We believe that news organizations should pay attention to who their audience is. And if their goal is to have a bipartisan readership, they will need to take intentional action to ensure that that is the case—at this point, it’s clear that a politically diverse audience will not happen by itself.

Quote of the Week

It is reasonable for journalists to feel frustrated and defeated about people who have a deeply entrenched—sometimes partisan-motivated—view that journalists are the enemy. But it is dangerous and inaccurate to assume that means distrust in the news is always connected to belief in conspiracies and separation from fact-based reality.