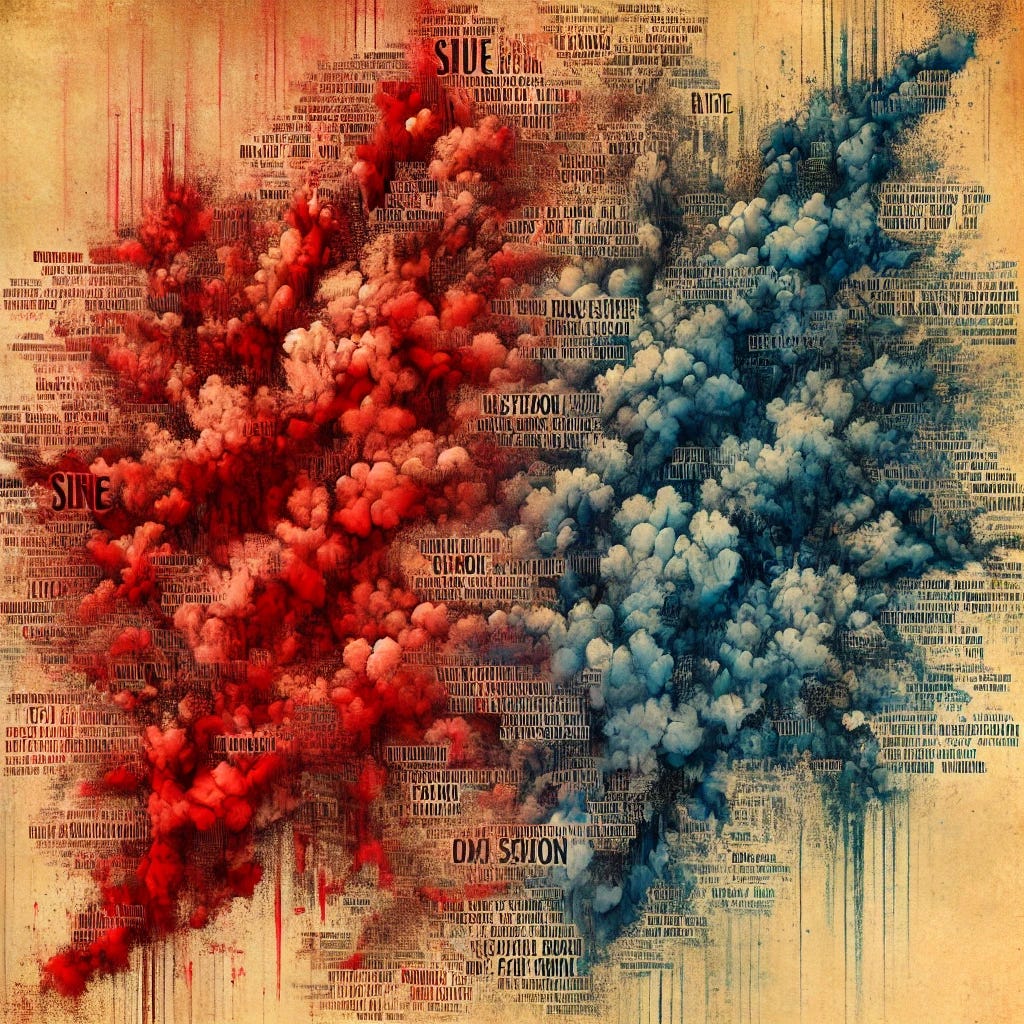

I Don’t Think That Word Means What You Think It Means

A new project builds a bipartisan dictionary – BCB #136

If you tune into C-Span or a political debate, you’ll notice almost immediately that when politicians in different parties speak, they use different words. A 2015 study from researchers at Brown University and Chicago Booth found that Red and Blue politicians have long used the different words when talking about similar topics, often with their respective political goals in mind: “undocumented worker” versus “illegal immigrant,” for example, or “tax breaks for the rich” as opposed to “tax reform.”

These differences, the researchers explain, “may contribute to cross-party animus, and ultimately to gridlock and dysfunction in the political system.” Looking at the state of political dialogue today, it certainly seems like that has proven true.

Same words, different meanings

Even when people use the same words, they don’t always mean the same thing. A 2017 study analyzed language used in presidential debates since 1999, and showed that the partisan divide comes with a semantic divide.

The researchers compiled a list of 213 single words and 397 word phrases, including politically charged words—such as "minority," "spending" and "justice"—used by American political parties. Then, they statistically examined how often words appear together in a sentence or in a speech, in order to figure out what speakers mean when they use them.

The researchers found that the meanings of words used in political context have changed over time and—more importantly for studies of polarization—are also differentiated between parties. For example, the study states, for Hillary Clinton, “business” was related to “education” and “help,” whereas for Donald Trump, “business” was associated with “deal” and “country.” Furthermore, concepts including “economy,” “education,” “healthcare,” “security,” and the “world” invoked different patterns of word associations between the parties and candidates. The researchers wrote:

To conclude, Americans seem to speak two different “languages,” politically implying different meanings in their mental representation of concepts, and these differences have created sub-cultures in modern society that underline citizens’ political behaviors, along with a wide gulf that hinders effective political dialogues and communication.

The researchers were also able to predict voters’ reported political affiliation with above 80% accuracy simply based on the way they organized a set of 50 political words in relationship to each other.

Language and trust

It’s not shocking that people across the spectrum use language differently. Words are the building blocks of our political atmosphere, especially when campaigning. Unsurprisingly, a 2024 study shows that people trust speakers who describe polarizing events “using ideologically-congruent language” more than those who describe the same events in a non-partisan way. For members of the media, deciding what language to use can be an important consideration that seriously impacts who trusts an outlet and who doesn’t.

In 2023, Tangle editor Isaac Saul released an editorial policy that outlined new language decisions, like choosing to use lowercase B “black” when writing about race, using “unauthorized migrant” and “unauthorized immigrant,” and some other changes around discussions of transgender healthcare. (You can read more about this policy in our interview with him.) As he wrote:

From reading feedback from the readers who unsubscribe, I’ve found we are still struggling to earn the trust of a larger audience.

One reason why, I believe (and have been told by those unsubscribing), has to do with the daily struggle of our language choices. Many readers on both the left and right have unsubscribed or written in angrily, not because of what we were saying, but how we were saying it. Whether it is calling cannabis “marijuana” (“that’s racist”) or referring to a trans person by their preferred pronouns (“that’s ceding the argument”), those readers didn’t even make it to the opposing arguments because they couldn’t get past the editorial decisions we were making on the way.

Bridging the language divide

So, if we don’t even mean the same thing when using the same words, how can we ever reach understanding?

A new tool from the MIT Center for Constructive Communication (CCC) aims to help us work past these linguistic divides by mapping them and offering alternatives to polarized language.

To develop the tool, research scientist Doug Beeferman and a team at CCC led by Maya Detwiller and Dennis Jen compared how FOX News and MSNBC assign different meanings to the same words or phrases. According to the tool’s information page,

This involved gathering approximately 18,000 articles from foxnews.com and 13,000 from msnbc.com published since 2021. The content was then split into millions of sentences for analysis. The first analysis measured the differences in usage frequency and sentiment. For those terms that show significant differences, a further qualitative comparison was done using a large language model (LLM) to describe the way the usage varies between the two outlets. The LLM was then prompted to provide evidence for its conclusions by citing specific references, as well as alternative "bridging" terms.

The most polarized words and phrases—like “illegals,” “gerrymandering,” “woke,” “evangelical,” “deniers” and “deep state”—are highlighted on the page. Users can also search hundreds of other terms to see the analysis for them.

We encourage you to check out the tool yourself, but to give you a taste, here’s an analysis of the word “radicals”:

Fox News uses the term "radicals" predominantly to describe individuals or groups perceived as extreme left-wing activists or threats to societal order, often in a pejorative sense. For instance, ① states, "Police face physical assaults from Antifa thugs and other radicals," framing radicals as violent and disruptive.

In contrast, MSNBC uses "radicals" more broadly to describe individuals with extreme views or actions, regardless of political alignment, and sometimes in a historical or neutral context. For example, ② mentions, "They are radical texts written by radicals in radical situations, full stop," without a clear negative connotation. Fox News uses the term more frequently to emphasize a narrative of societal threat and political opposition, often linked to current events and political figures.

Beyond the assessments of word usage, the dictionary also includes suggestions that aim to help users get past contentious language divides and closer to understanding. For example, in place of “radicals,” the Bridging Dictionary suggests using “extremists” or “activists,” “as these can be used to describe individuals with intense views or actions without the same level of inherent bias.”

In a web post, CCC Senior Advisor Andrew Heyward said the creators are actively seeking feedback on how they can improve the model, and are curious about how it could be used. They imagine academic researchers and journalists could find value in the dictionary, but said some of their colleagues in journalism were skeptical that journalists would want to embrace substitute words suggested by an algorithm.

Quote of the Week

What’s the difference between an “undocumented worker” and an “illegal alien”? If this sounds like the setup for a groan-worthy political joke, it is—in a sense. The unfortunate punch line? It depends on whether you’re a Democrat or a Republican.

In which of the two argots is the bare word "immigrant" routinely used to refer only to those present in the United states without authorization?