Election denialism across the aisle - BCB #33

Also: Science-backed strategies to prevent partisan animosity, and health data shows partisanship is literally killing us

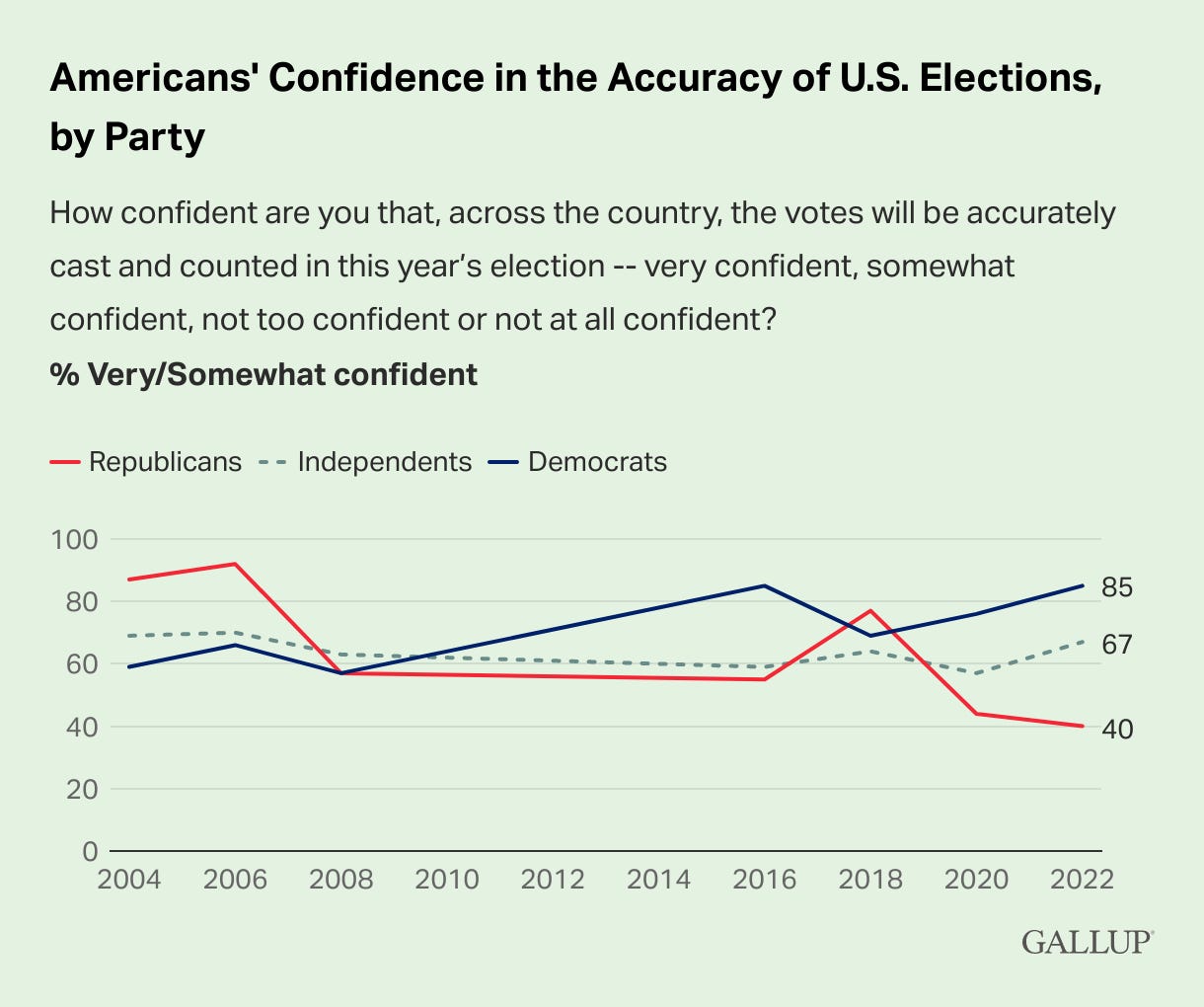

It hasn't always been Red who doesn't trust elections

In our 29th issue, we noted that Red faith in election results was up 30 points from 2020 to 2022, and questioned whether the skepticism of 2020 was part of a long term loss of confidence or just an outlier. We found earlier data which suggests it’s sort of both.

Gallup’s tracking of election confidence for the last two decades (which is worded a bit differently than the Pew survey we discussed previously) shows that while Red confidence has been slowly declining, they haven’t always been the more skeptical side. In 2004, 87 percent of Red voters had faith in the electoral process, versus 59 percent of Blue, presumably due to the drama around the 2000 election between Bush and Gore. Later Red doubts began long before Trump. The election of Obama in 2008 saw Red faith in the electoral process drop 30 points to 57 percent. But by 2018, Blue again had less trust in elections. Unsurprisingly, these events show that the losing side is the one more likely to distrust the results.

In other words, while Red election denialism is at historically high levels, this should be understood as an escalation, not an innovation. There is a corresponding, though somewhat less extreme, history of Blue election denialism.

Four science-backed strategies to curb partisan animosity

This article covers four strategies the readers of the Bulletin have probably heard before: correcting misperceptions about how extreme the other side is, dialogue that emphasizes listening and curiosity rather than persuasion, being aware that exposure to the other side can actually increase conflict and polarization if it’s not handled carefully, and disagreement without dehumanization.

The “science” behind this comes from the recently published study that this article summarizes, which reviews and categorizes depolarization interventions based on whether they target thoughts, relationships, and institutions. The idea is that correcting misperceptions will allow for positive relationships which will then motivate people to change polarized institutions.

The study mentions some interesting conditions that seem to be associated with better relational outcomes. For example, the ingroup and outgroup should have more or less equal socioeconomic status, support authority and the law in general, and preferably have common non-political interests that would incline them towards friendship.

Political partisanship kills, according to health data

We have already reported that people living in more conservative parts of the United States have borne a disproportionate burden of illness and death due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This new study further showed that life expectancy for individuals of working age is a lot lower in states with more conservative policies. However, saving the most lives would actually require a mixed menu of policies from both conservative and liberal ideologies:

More conservative marijuana policies and more liberal policies on the environment, gun safety, labor, economic taxes, and tobacco taxes in a state were associated with lower mortality in that state. Especially strong associations were observed between certain domains and specific causes of death: between the gun safety domain and suicide mortality among men, between the labor domain and alcohol-induced mortality, and between both the economic tax and tobacco tax domains and CVD [cardiovascular disease] mortality.

The unlikelihood of such a policy mix actually happening says a lot about polarization’s dangerous impact.

Quote of the Week

A GOP victory that significantly boosts the ranks of election deniers in Congress and in state‐level public office will not plunge the United States into a political Armageddon. But it may very well jeopardize, at least for the foreseeable future, the integrity of our elections.