Earlier this month, people took to the streets in over 1,400 marches in all fifty states to protest what they call a “hostile takeover” of American democracy and an attack on people’s rights and freedoms. Organizers estimate that somewhere between three and five million people participated.

You may not have known that. While we couldn’t find any hard data, it certainly seems like the April 5 protests generated only a smattering of media coverage, far less than the headlines around 2017 protests like the Women’s March.

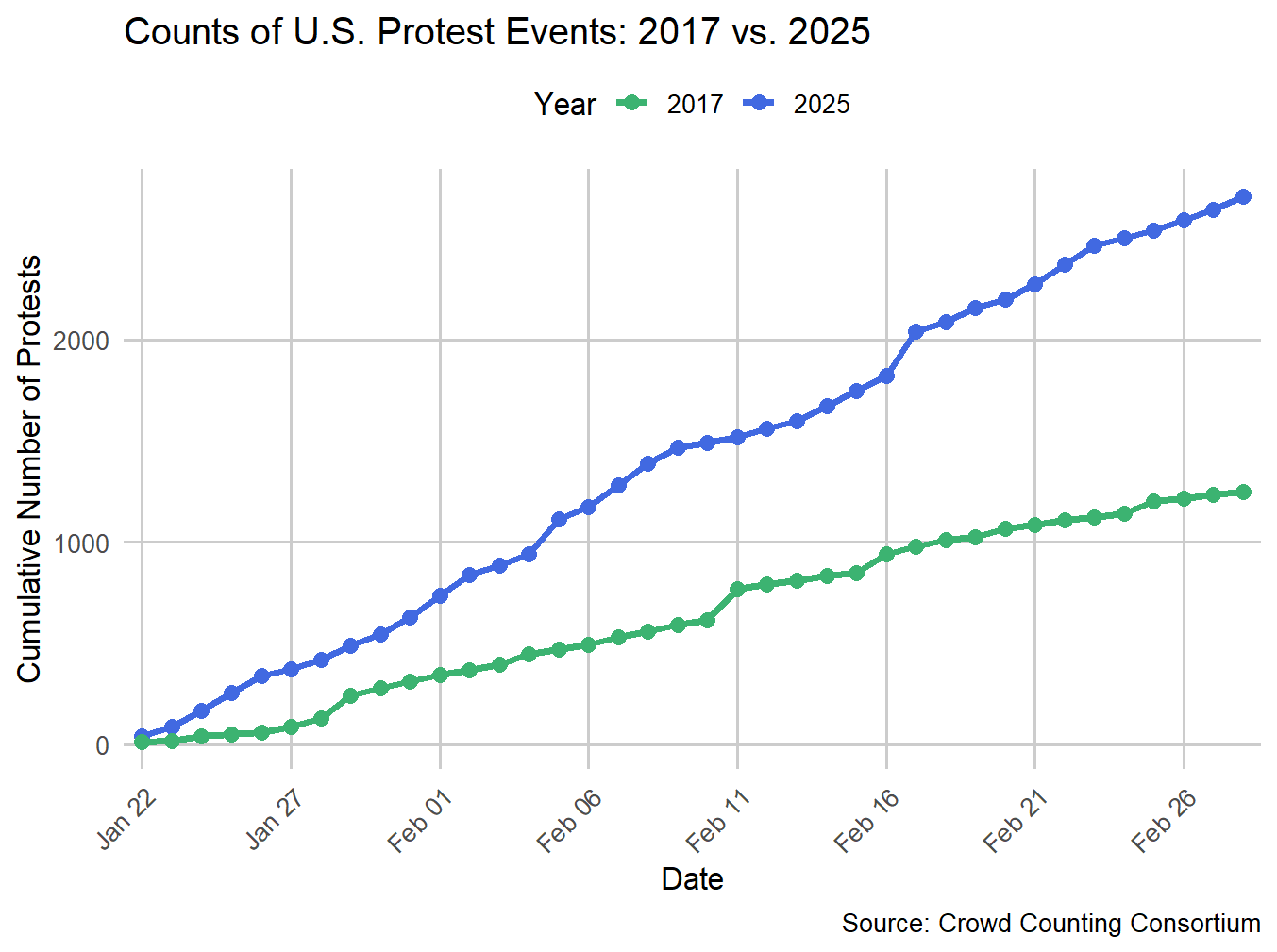

In fact, if you look at the last couple months’ protests compared to the same period in Trump’s first term, it turns out that there have been twice as many protests in 2025 compared to 2017. However, each individual protest has generally been smaller than in 2025.

Does any of this matter? Do protests even work, when faced with limited media coverage and authorities who cannot be shamed?

We think the historical record is quite clear on this point: protests are effective. They move votes, and they even dislodge dictators. Surprisingly, they are even more effective than armed revolution. But the details matter—not all protests are equal.

Yes, protests move voters

On Tax Day in 2009, the then-nascent Tea Party movement hosted coordinated rallies across the country advocating for an agenda that was, at the time, decisively to the right of the status quo. Several years later, a group of political economists looked back at these events to measure their impact on American politics and found that in places where there was higher turnout, there were

significant consequences for the subsequent local strength of the movement, increased public support for Tea Party positions, and led to more Republican votes in the 2010 midterm elections. Policymaking was also affected, as incumbents responded to large protests in their district by voting more conservatively in Congress. Our estimates suggest significant multiplier effects: an additional protester increased the number of Republican votes by a factor well above one. Together our results show that protests can build political movements that ultimately affect policymaking, and that they do so by influencing political views rather than solely through the revelation of existing political preferences.

(A statistical note here: careful readers will worry that the correlation between protest size and vote outcome may just be due to pre-existing local political attitudes. This research and others correct for this problem by using rainfall as an instrumental variable—it’s a random event that affects turnout independent of local politics. )

There’s evidence to suggest that left-leaning movements during Trump’s first term were successful too. In 2018, researchers studied the protests that took off after Trump’s 2017 Muslim ban and found that a “rapid shift in opinions occurred shortly after President Donald Trump signed executive order 13769 into law.” A 2021 working paper found that Women’s March protests in 2017 “increased political preferences for women and people from ethnic minorities in the 2018 House of Representatives Election” regardless of their party affiliation. Whether or not Trump admits it, historians have argued that these movements may have affected the President’s actions more than we realize.

Hot off the press, a recent paper examines the impact of the Black Lives Matter protests following the death of George Floyd on the 2020 presidential election. They found that there was a significant increase in Democratic votes in counties with high turnout at protests, even when the protests initially generated conservative backlash. (Once again, rainfall was used as an instrumental variable.) They also found that the protests “altered attitudes towards affirmative action and the role of slavery in explaining current racial disparities,” though they qualify that “some of these effects likely only pertain to peaceful protests.” Unfortunately, this paper did not try to distinguish between the effects of violent and non-violent protests, which is crucial as we will see below. (About 6% of BLM protests, or 620 out of 10,330 recorded events, included protestor violence.)

It’s important to note that effectiveness is not the same thing as being liked. Generally, people only support the rights or protestors when they agree with the cause. And yet, protests often work anyway.

Size matters

Sometimes protests work, but not always. Digging into this question, political scientists Maria Stephan and Erica Chenoweth undertook one of the most comprehensive studies of protest effectiveness ever. They first created a data set of 323 violent and nonviolent mass movements between 1900 and 2006, including every major movement with a “maximalist” political goal: secession, regime change, or expulsion of a foreign occupation.

Analyzing 160 variables for each case, they homed in on four key criteria for success:

The movement needs to have a large, diverse, and sustained group of participants

It needs to elicit loyalty shifts among security forces and other elites

It must use a wide variety of methods, not just protests

When it is repressed, it doesn’t descend into chaos or resort to violence

In particular, they found that “no government has withstood a challenge of 3.5% of their population mobilized against it during a peak event,” what she calls the “3.5% rule.”

Crucially, Chenoweth explained in a 2020 follow-up, the 3.5% number is a useful rule of thumb but not the be-all and end-all determiner of a protest movement’s success. Other factors like momentum, organization, leadership, and sustainability matter as much as large-scale participation. In fact, they’re often prerequisites. Additionally, there has been at least once recent instance—in Bahrain between 2011 and 2014—when a nonviolent movement that hit the 3.5% threshold failed to achieve its goals. Yet the majority of mass nonviolent movements achieve some success even without the active participation of at least 3.5% of the population.

Coalition Building is Key

The organizers of the “Hands Off” movement have cited Chenoweth’s rule, saying that they are aiming to get 3.5% of the population participating in upcoming actions. But they may need to work on broadening their coalition in order to generate that volume of active support. So far, it seems that participants in these anti-Trump protests have skewed older — lots of boomers and few Gen Zs. Sociologist Dana Fisher found that at the April 5 protest in D.C. participants

were mostly female, predominantly white, highly educated and middle-aged (the mean age was 49 years-old and the median age was 51). In comparison to the first Women’s March in 2017, HandsOff2025 in DC was less female, more white, and quite a bit older.

Why aren’t young people more participatory? Social movement researcher Thomas Zeitzoff speculated on Bluesky that they could be questioning the efficacy of protesting, worrying about the ramifications of speaking up, or just feeling alienated by politics altogether. On his blog, political scientist Jay Ulfelder offered a few additional explanations. First, he pointed out that much of the organizing for the Hands Off protests took place on platforms more likely to be popular with older constituents, like Facebook, Bluesky, and Instagram. What’s more, the issues at the heart of this new movement—federal job and spending cuts, for example—and the patriotic language it’s using are less likely to resonate with young folks, who are more concerned by issues like Gaza, climate change, and police violence. As Ulfelder explained:

Everyone in the potential coalition agrees that fascism is bad, but they don’t all have a common understanding of what fascism is, and I think a lot of the younger folks in it carry a lot of anger and resentment at their elders for what they see as a long tradition of tolerating or even supporting certain fascistic features of the current system that work alright for them.

Violence hurts your chances

When protesters engage in violence, even in response to state repression, it almost always hurts their cause. Political scientist Omar Wasow examined the 130 violent protests that occurred in the week after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in April 1968, and found that “if your county was proximate to violent protests, then that county voted six to eight percentage points more toward Nixon in November.” By contrast, “nonviolent protest achieved many of the same sorts of outcomes that the more militant activists were fighting for without splintering the Democratic coalition,” notably moving the country towards dismantling Jim Crow laws.

Such are the vicissitudes of the culture war that tweeting this research during the height of the 2020 BLM protests got leftist data scientist David Shor fired. But heated arguments about the morality of meeting state violence with protestor violence are pointless if it doesn’t actually work — and Wasow’s result isn’t just a one-off.

The historical record shows that nonviolent protests have been much more effective than violent ones. Stephan and Chenoweth again:

in the face of regime crackdowns, nonviolent campaigns are more than six times likelier to achieve full success [regime change, secession, or expulsion of a foreign occupier] than violent campaigns that also faced regime repression. Repressive regimes are also about twelve times likelier to grant limited concessions to nonviolent campaigns than to violent campaigns.

A more recent analysis shows that even adding a small violent wing to otherwise non-violent protests hurts their chances.

There are multiple reasons why violence makes success less likely. First, many more people can undertake non-violent protest than violent actions, including old people and families. Second, success often relies on the defection of the security forces (see above) which is a lot less likely if those same forces are trying to repress violent actors. Violence is not only morally suspect, it’s a strategic failure.

Another key advantage of nonviolent resistance is that there are so many ways to do it. As we’ve previously written, there are plenty of ways to participate in effective nonviolent protest even if you don’t want to march in the streets:

Some of these tactics are obvious (“public speeches”, “pickets”, and “letters of support”). Some rely on humor to ridicule authority (“mock awards”, “public disrobing”). Some are meant to harass (“rude gestures”, “haunting officials”). There are tactics of economic disruption (“consumer boycotts”, “withholding rent”, or just “staying at home”) and ways to fight institutional power (“reluctant and slow compliance”, “overloading of administrative systems”, and “quasi-legal evasions and delays”).

Image of the Week

Thanks for the survey of the literature!

I should probably go read these papers but I had some questions: for the papers that show that there was an increase in Democratic votes in counties with protests (both for the Women's March and BLM), are we also talking about counties that voted Republican? Or are we only talking about Democratic-voting counties?

I ask because I suspect that the mechanism of persuasion of protests in the US might be significantly different than other countries that are not as ideologically polarized. As Erica says above, the logic of protests might be different when there's a single ruler who does something truly unpopular (the recent South Korean protests against the declaration of martial law) and everyone turns up against the action. But in US protests, what's the composition of Blue and Red voters, especially the US has gotten more and more polarized?

Fabio Rojas and Michael Heaney find in "Party in the Street," their analysis of the Iraq War protests, that these protests were dominated by Democrats in the Bush years but most of the Democrats stopped participating once Obama became president and continued the Iraq war (even as he took steps to start winding it down).

I suspect also that because protests in the US are organized by one team (Red or Blue), they don't seem to be oriented much around persuading people who may be skeptical of them. For instance, the protest in Berkeley recently seemed to me to be aimed mostly at people who already believed in academic freedom rather than convincing people who are agnostic on academic freedom and/or skeptical of universities.

I'm wondering how relevant Chenowith's data is to the current situation. Was she mostly looking at truly autocratic regimes with unelected dictators and mass movements were able to oust them? Or does her data include pressure campaigns in democratic countries? The reason I ask is b/c the big question on my mind with the protests is: What exactly is the goal? Assuming we're not gonna impeach Trump for a third time (please God, no), what is there to do other than pressure Republican members of Congress to stand up to him?