Do Your Politics Make You Easy To Troll? - BCB #84

Also: researching fake news makes you more likely to believe it, and threading the needle between “Black Lives Matter” and “all lives matter”

Who is easiest to troll online?

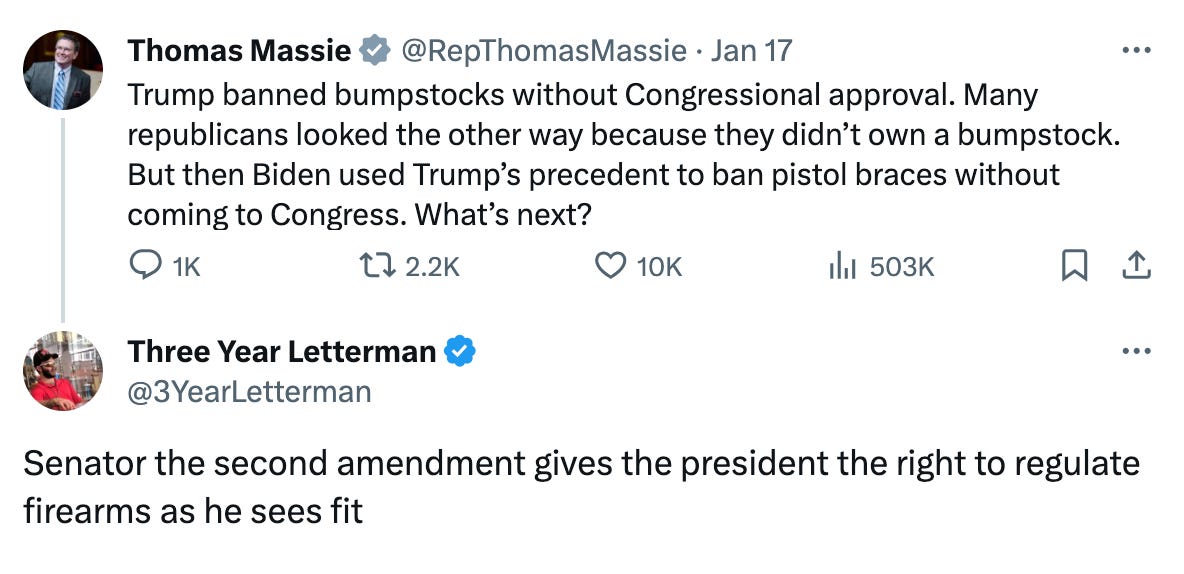

3YearLetterman is an absurd parody of a “youth football coaching legend.” Over the last few years, he’s been getting into politics, saying outrageous things to provoke responses that reveal a deeper truth.

The long-time political satirist recently put together a list of who’s easiest to troll.

Self-importance - this is EASILY the trait that has the strongest correlation to taking the bait. People who take themselves seriously simply cannot resist the urge to tell someone else they are wrong

Age - The Boomers and Gen Z are the easiest to troll for very different reasons. Millennials and Gen X are the hardest. …

Politics - I haven’t really noticed a left or right correlation. Sometimes it seems like liberals take the bait more and sometimes it seems like conservatives do, but it all balances out. ... Often the same post will have people calling me both a “Trumptard” and a “libtard.” ….

Education - The easiest people to troll are (1) Those [in] academia and those with advanced degrees, particularly those who list their degrees in their Twitter bio; and (2) Homeschoolers/those who were home schooled or who went to a primarily religious school. Your average HS or college graduate is harder to troll because they’ve spent more of their lives around normal people and don’t take themselves as seriously.

Eating Meat - Vegans are obscenely easy to troll.

While there isn’t a lot of science on who’s easiest to troll, what there is backs him up. We’ve previously covered how academics and people who have high self-importance are more likely to take politics very seriously.

But why troll at all? For 3YearLetterman, the point is to reveal our sensitivities. We all have triggers that can cause us to react badly, even when we are trying to do right. He explains his motivation:

If nothing else, what I wanted the account to do is make people not take themselves so seriously. … My view is that about 0.01 percent of the time, things happen that are truly important and truly matter. You have to reserve your emotions for those times.

Part of what makes conflict intractable is our unconsidered emotional reactions. At its best, 3YearLetterman’s outrageousness injects incisive humor into Twitter's oh-so-serious discourse. He’s the court jester, using humor to reflect our flaws in a disarming way.

Asking people to “do their own research” increases belief in misinformation

A recent study in Nature reveals that contrary to expectations, researching false claims online increased the likelihood of believing them.

Participants were asked to evaluate the accuracy of news articles, both real and fake, by using a search engine to find evidence. These experiments consistently showed an increase in belief in false claims post-research. There was a 19% increase in the probability of rating a false article as true among those who “did the research.”

How does this happen? One reason is data voids, topics on which there isn’t much high-quality information yet – such as recent rumors.

Our results indicate that those who search online to evaluate misinformation risk falling into data voids or informational spaces in which there is corroborating evidence from low-quality sources.

The study also examined the impact of searching for belief in true news, finding that it increased belief in true news from low-quality sources but had inconsistent effects on true news from mainstream sources. This highlights the role of search result quality in shaping beliefs.

In many ways this is a disappointing result. We can’t just ask people to be more diligent in their reading, if there isn’t good material to read. Instead, the authors emphasize the need for experimentally validated media literacy programs – we have to actually test our suggestions for how to evaluate information – and improved search engine strategies to combat misinformation.

Talk about specific harms, but justify action on universal principles

Why is “All Lives Matter” offensive (to some) even though it’s obviously true? And why do (some) people feel a need to say it in response to “Black Lives Matter”? Matt Lutz points out the difference between using language that emphasizes common human experiences (“universal” language) versus focusing on the issues facing specific groups (“particular” language). This insight is crucial for understanding how people talk past each other on certain highly polarized topics.

Any moral demand that centers the rights and dignity of one group and one group alone will give rise to suspicion about the speaker’s attitude towards other groups. After all, why not mention other groups? Why not phrase your concerns using universalistic moral language? These kinds of thoughts are not the product of paranoia. They’re a common way of parsing language.

…

Things are not quite so simple, though. … If some person or group has been injured, refusing to acknowledge their particular circumstances and instead talking about other people implies that the injury of the particular person or group is not especially relevant. Suppose someone responds to your plea of “I have a problem” with “We all have problems.”

Lutz suggests we can satisfy both groups by talking about specific harms but appealing to universal moral principles. He gives the example of the famous “I have a dream” speech by Martin Luther King Jr., which includes a list of specific grievances:

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: for whites only.

But King then urges us to take action by appealing to universalist ideas such as the greatness of America and its founding principle of equality:

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

Lutz suggests that this pattern is the way to thread the needle between in-group concerns of specific harms and outgroup concerns of special treatment.

Fortunately, there’s a way to avoid this miscommunication. Be particular when talking about problems, but universal when discussing the moral principles that we use to guide solutions.

Quote of the Week

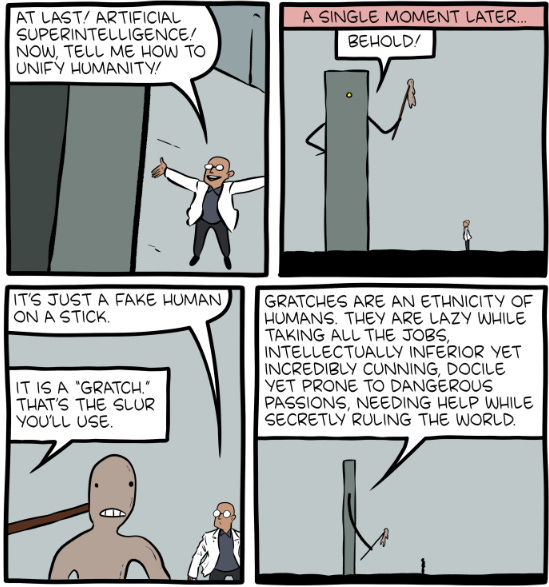

- Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal

Image prompt: The jester’s exaggerated and fun costume, along with a lively pose and a smartphone, embodies the spirit of a mischievous online satirist. The crowd’s reactions have a slight comedic undertone, and the background is simplified, ensuring the image remains engaging and easy to understand in a smaller format.

*sigh* You made a statement about *me* in the first line of your post. You tell me that researching fake news makes *me* more likely to believe it. This is not a statement about statistical averages; as phrased, it's a statement about me - and about all your other readers, individually.

I find this absolutely non-credible. If I "assume good faith", I can explain your choice of phrasing in terms most common in literature classes, that deny that you meant what you said, or expected any reader to understand it as you said it.

But most of the time, when randos say things like that, they mean what they said. Their statement applies to everyone, or at least everyone worthy of treating as human. Moreover, the evidence for their statement is usually "I want it to be true", though they probably expect to be believed primarily because of credibility granted to people of high status, however clueless and/or dishonest they may be.

Several paragraphs later, you explain what you mean. Of course it wasn't what you said; that explanatory paragraph was consistent with statistical explanations, and says nothing about your individual reader. It was, however, incomplete, so I clicked through to find out whether the "19% increase in probability" was evenly distributed across all subjects and topics, or whether it clumped - perhaps some people were incompetent at evaluating sources, and others were not.

I got more than I bargained for. The headline claim in that Nature article appears to be that using online searches brings up enough poor quality information that people "informed" by this source may well become more misinformed than before they started looking. (I haven't yet read far enough to see what their data supports.)

Sadly, that fails to surprise me. Search engine results have gotten worse and worse at giving the kind of results I generally want. Some of this is a lowest-common-denominator problem; I'm not the average search engine user. But a lot of it is simply that search engine providers quite naturally prioritize their own income, which comes from advertising, including having their search results send people to sites run by paying customers. And some of it, I think, is that people in tech management - at least those supporting a mass market user - put very little emphasis on quality.

But you may need to give some thought to being part of the solution rather than part of the problem.