DEI Programs Aren’t Making Us More Tolerant. What Will? – BCB #121

Also: how music taste maps onto politics, and a hopeful story of a free speech debacle gone right.

A few years ago, it might have been hard to predict the growing consensus that university DEI programs aren’t working. In a recent essay for Persuasion, Rachel Kleinfeld makes the case for How To Fix DEI. Normally, a piece with this sort of title would be terrible—it would either be a scathing screed against political correctness, or an accusatory exhortation to “do better.” But Kleinfeld takes the long view, making the connection between DEI initiatives, polarization, and democracy, and offers a refreshingly cogent case for where DEI programs should go next.

Demographically, America is in the middle of a long transition away from having one dominant culture (“White, male, straight, and Christian”) towards a truly pluralistic democracy—something no large country has ever successfully done. Kleinfeld takes as a starting point the idea that DEI initiatives, in every form they take, emerged to achieve what she calls the “goals of pluralism”:

Foster widespread acceptance of a diverse society among the dominant culture.

Build greater equality of power and voice for members of previously marginalized groups.

Give all races, ethnicities, and sexual and gender groups a feeling of inclusion and belonging as equal members of a shared culture, not add-ons to a dominant norm.

But there’s very little evidence that DEI programs in their current form are an effective way to achieve these goals. Studies examining the efficacy of DEI initiatives have been largely inconclusive, and have mostly been lab experiments rather than attempts to look at the usefulness of programs that exist out in the world.

What’s more, there have been studies indicating that “DEI interventions may trigger retrograde attitudes,” especially among white people, notably white men. The solution many organizations have chosen—making DEI programs mandatory—has only brought about more backlash. Regardless of their politics, Kleinfeld notes, “people don’t like being forced to do things.”

A related issue is that the “anti-racist” ideology that many DEI programs are built on encourages people to see themselves based on the identity they are born into, which generally falls into one of two categories: oppressed or oppressor. Even if the values these programs promote have merit, the worldview they espouse can be incredibly divisive, and hard for people to slot themselves into—especially the people whose hearts and minds these programs most want to change:

It sure looks as if DEI as it is currently being practiced is adding bricks to the very wall its proponents claim to want to knock down. While leaders of the MAGA movement are spearheading the greatest rollback of women’s rights in fifty years and contributing to an atmosphere in which hate crimes and threats against minorities and women are at the highest point this century, DEI as it is popularly practiced appears to be motivating more people to support these noxious goals.

If this is true—and Kleinfeld makes the argument much more carefully than partisan critics—where do we go from here? For DEI programs to actually work towards the goals of pluralism, Kleinfeld has a couple suggestions:

1. Insist on equality and inclusion for all… To create a more equal society, we must engage in diversity programming in which those from both minority and majority identities see the initiatives as potentially positive for them and the groups with which they identify…

2. Complexify identity… Programs to embrace diversity should make room for all people to have complex identities in which all their parts do not line up with the majority of their group. In the words of Diana McLain Smith “closing the distance across groups … requires us to open up the space within groups.” This entails accepting the diversity within as well as between groups…

3. Require rigor and curiosity… Words can lead to violence—and as a scholar of political violence, I know that a very particular type of dehumanizing speech does precisely that. But conversations that explore ideas—even ideas that make some people uncomfortable—are fundamentally different, if they are pursued in a setting of respect for individuals and curiosity…

4. Deepen a sense of agency and possibility… A pessimism pervades the DEI movement. While claiming to want massive structural change, many DEI tenets simultaneously imply that such change is impossible… But if change is possible, and one claims to want it, that forces students to make the effort to understand how to get there and to take responsibility for the outcomes of their actions.

Regardless of where you stand on the goals or politics of DEI, Kleinfeld argues that today’s DEI programs are counter-productive in the sense that they are contributing to the polarization they hope to reduce.

How do Swifties vote?

We all know that polarization shapes culture. But if latte-drinkers are Blue and gun-owners are Red, what about R&B listeners or Taylor Swift fans? A group of researchers recently put together an interactive online tool that shows you how the listeners of any of the top 1,000 artists in the United States identify politically, and how that political leaning has changed in the last seven years. As one of the tool’s creators explains, “this index measures the relationship between music streaming patterns across regions and the voting patterns of those regions in the 2020 election.”

For example, you can see below that the politics of Taylor Swift’s listeners have moved around quite a bit, skewing further left from 2018 to 2021 before heading back towards the center.

The tool also allows you to look at the political leanings for listeners of different genres. Unsurprisingly, country listeners skew right and world music listeners skew left, but other genres are a little more unexpected. Who knew, for instance, that the politics of R&B, Hip-Hop, and Rap listeners are so all over the map?

A Town Library Canceled A Controversial Event—Then Changed Its Mind

Last spring, the public library in the town of Tewksbury, Massachusetts found itself in free speech hot water. After holding a virtual event on transgender athletes featuring a trans author and activist, the library invited Gregory Brown, a professor of exercise science, to give a talk called “Males and Females Are Different, and That Matters in Sports.” The event was scheduled for earlier this month, but shortly beforehand the library issued a news release:

In considering this program and resulting comments, we discovered a lack of statistically significant research to support either viewpoint favoring or disfavoring transgender participation in sports. We determined that we cannot facilitate a factual, good-faith presentation on this topic as we had hoped. In addition, the levels of intolerance for discussion around this issue has brought bullying to our staff.

It’s easy to imagine the endless, emotional, barely on-topic email threads that must have led to the (literal and figurative) cancellation. But this is actually a rare story of a free speech kerfuffle gone right. As writer Megan McArdle explained in her column for the Washington Post, when she caught wind of the event cancellation she contacted Brown to find out more about what had happened, and learned something promising:

He told me that within the past hour, the library had reached out to him and asked him to give his talk after all, possibly because there was strong pushback against this decision by members of the community.

The event was rescheduled for just a few days after it had initially been planned. To be clear, this isn’t good because transgender athletes clearly should or shouldn’t participate in various competitions. This is a good outcome because that question is genuinely complex, and won’t be resolved by either side insisting they’re right.

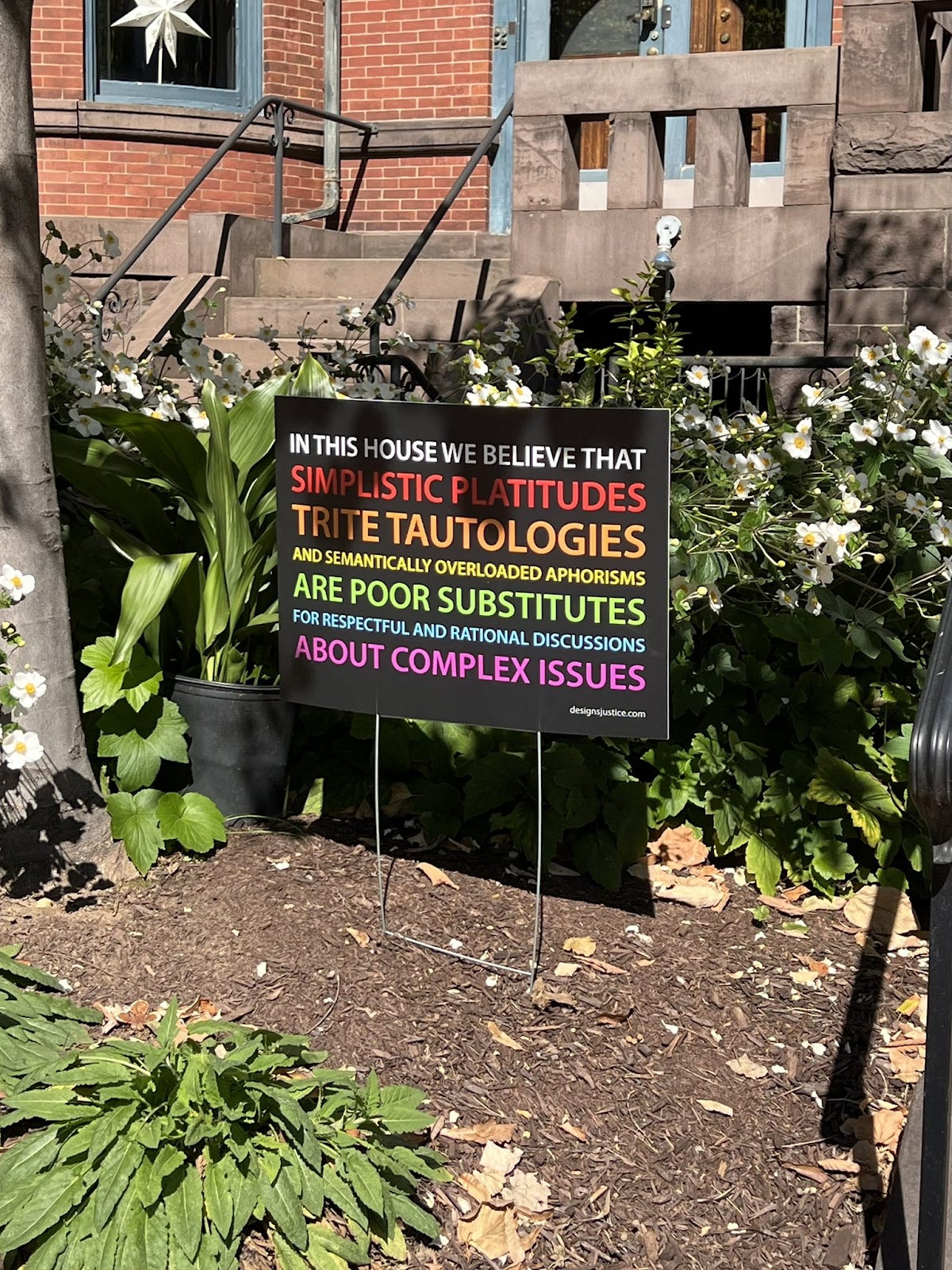

Image of the Week

(Source)

It's good to see that people with credentials that get them listened to have begun to notice what was obvious to me, 20 years ago, when I was first subjected to a compulsory DEI screed. Rachel Kleinfeld isn't the only one; I recently read a quite decent book by Canadian sociologist Sarita Srivasta on the same topic.

"Convince a man against his will; he's of the same opinion still". That goes doubly if you insult him (or her) in a context where it seems socially dangerous to respond - they might e.g. get in trouble with HR and perhaps lose their job. So now they disagree with you *and* feel bullied and therefore angry.

It's a minor miracle that repeated clumsy attempts to convince me of my incurable racism (as evidenced by the colour of my skin) haven't converted me to an actual racist (as the term was used in my youth, not "person from a culture with systemic racism"). But I'm on the autistic spectrum, so I lack various "normal" social instincts - 40 years in the USA and I still don't assign identities based on race to myself or others. I can't even always correctly label people I meet, unless they label themselves.

And yes, I realize that my continuing belief in race-blindness is an offence against anti-racism. It's also one that 40 years of non-arguments haven't shifted, even while they did appall me with the depths of the race-targeted bad behaviour routinely experienced by visible racial minorities, particularly black men.