Crime in DC is a Problem, or Maybe It Isn't

We are measuring different things and talking past each other - BCB #161

Trump sent federal troops to Washington D.C. this week to fight "violent gangs and bloodthirsty criminals." Is there actually a crime wave in DC? It depends on what you mean, and part of the reason that this subject is so difficult is that different people mean different things.

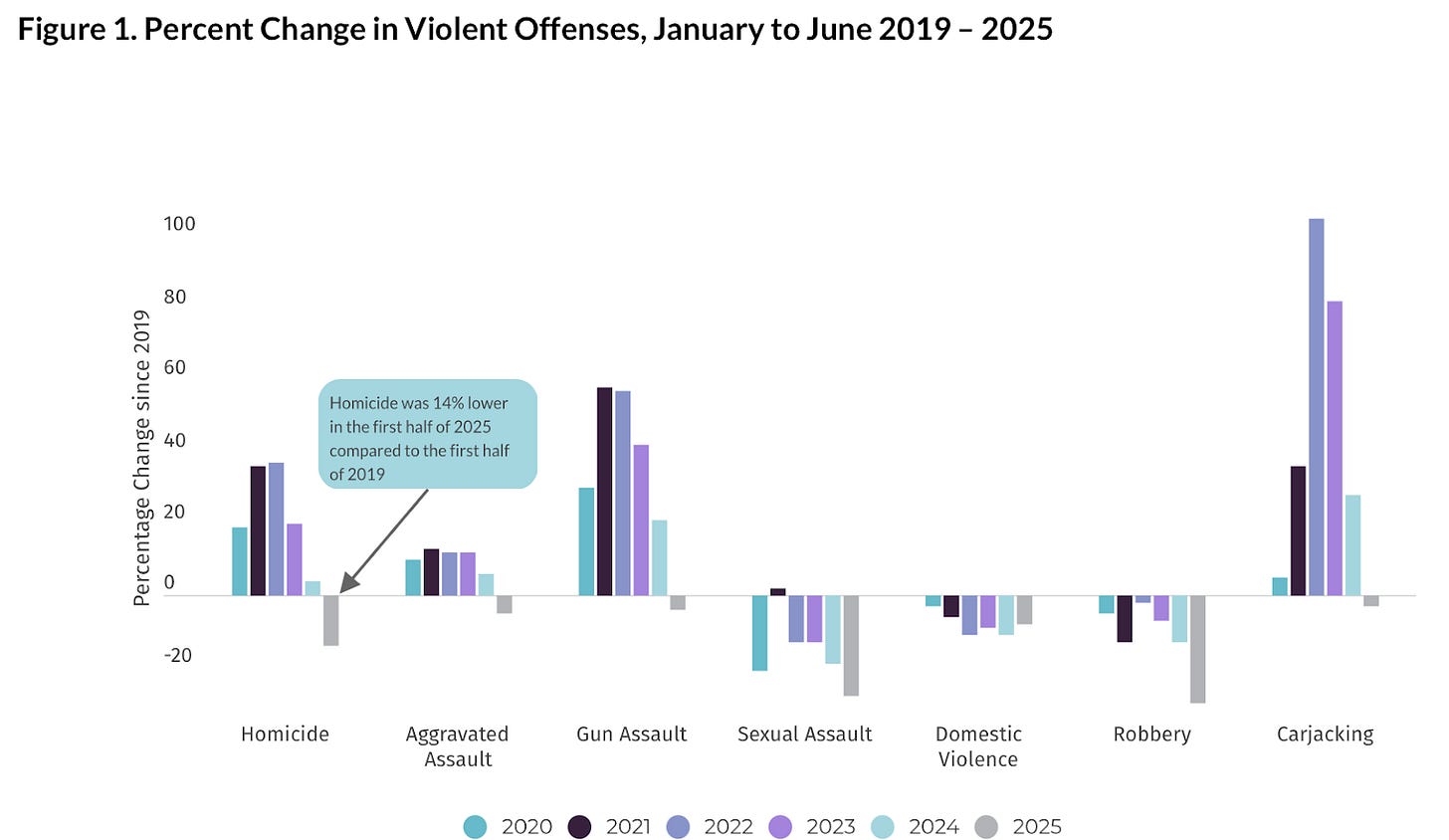

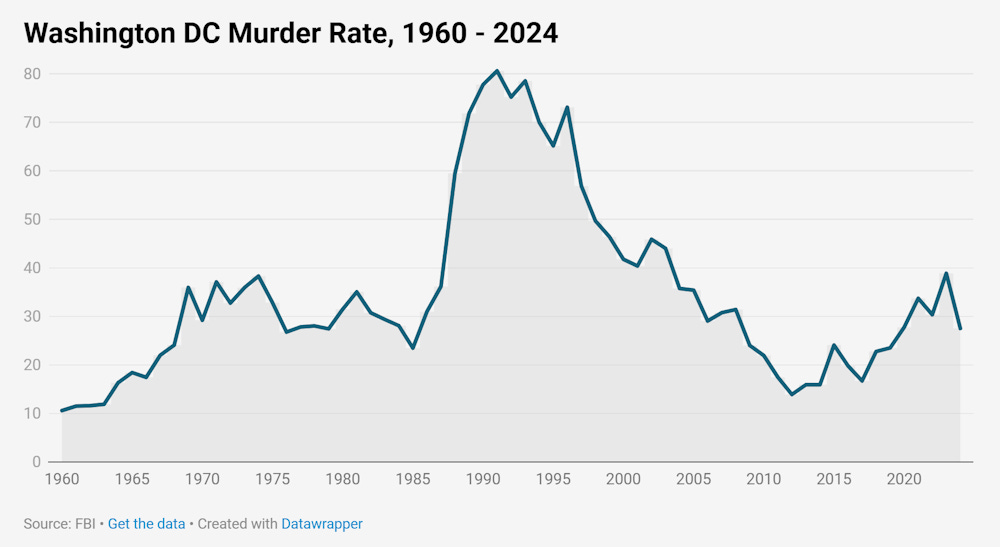

First we have to deal with exaggerations and inventions. In announcing his decision to send the National Guard into DC, Trump said “Murders in 2023 reached the highest rate probably ever.” That’s simply false – murders in DC have been falling for decades, and 2025 is on track to be the lowest ever.

And yet, Trump has tapped into something. Americans feel unsafe. Crime is generally down, both over the long term and after a post-2020 bump, but concern is up – and it’s polarized. In Gallup’s latest poll, while Americans across party lines agreed crime is a serious issue nationally, Republicans were far more likely than Democrats to say crime is “extremely/very” serious and to believe it’s rising, even as national measures fall.

So why does the concern over crime diverge from the decades-long success story of falling crime rates? And how has it become partisan? We see a number of major reasons why the argument over public safety continues without any resolution:

“Crime” is not one number. Different measures, different categories, different years will produce different answers.

Even if the trend is down, absolute numbers may still be high.

Where you live matters more than the national average. Safety is hyper-local, so a few blocks can define a city for those who live there.

Different people frame the same facts in wildly different ways, so that we each see wildly different causes and solutions to crime.

"Is crime up?" depends on what you mean

“Crime” isn’t a single number – it's dozens of different measures that can tell completely different stories depending on what you count and how you count it. Ask instead: which crime, what period, which place. Year-to-year spikes in one category can coexist with multi-year declines overall.

Further, “crime” means different things to different people! When one study asked Americans what “crime” meant to them, Republicans pictured theft and disorder, while Democrats pictured shootings and gun violence. These genuine divergences in perception can become politically weaponized. When “crime” can mean anything from turnstile jumping to domestic terrorism, rising car thefts become proof that Democrats are soft on crime, while mass shootings become proof that Republicans don't care about safety.

There isn’t even agreement on whether Red or Blue America has worse crime. Change the time period, the location, or the type of crime, and you can make either story sound definitive:

Seemingly minor research decisions—such as whether to analyze data at the state or at the local level—can drastically change results. If we look at the county level, Democratic areas seem particularly murder-ridden; but when we look at the state level, Republican states are clearly more violent. Casual consumers of empirical social science research often fail to appreciate all the ways in which researchers can manipulate the data to say whatever they want.

The most careful study of 400 cities found no detectable effect of a mayor's political party on overall crime rates, whether at the state or county level – but voters and media keep sorting outcomes into Red and Blue buckets.

These tricky definitional issues mean that we tend to argue past each other about fundamentally different problems. Neither side is wrong about their concerns, but they're not actually debating the same numbers.

Murders are down but still high

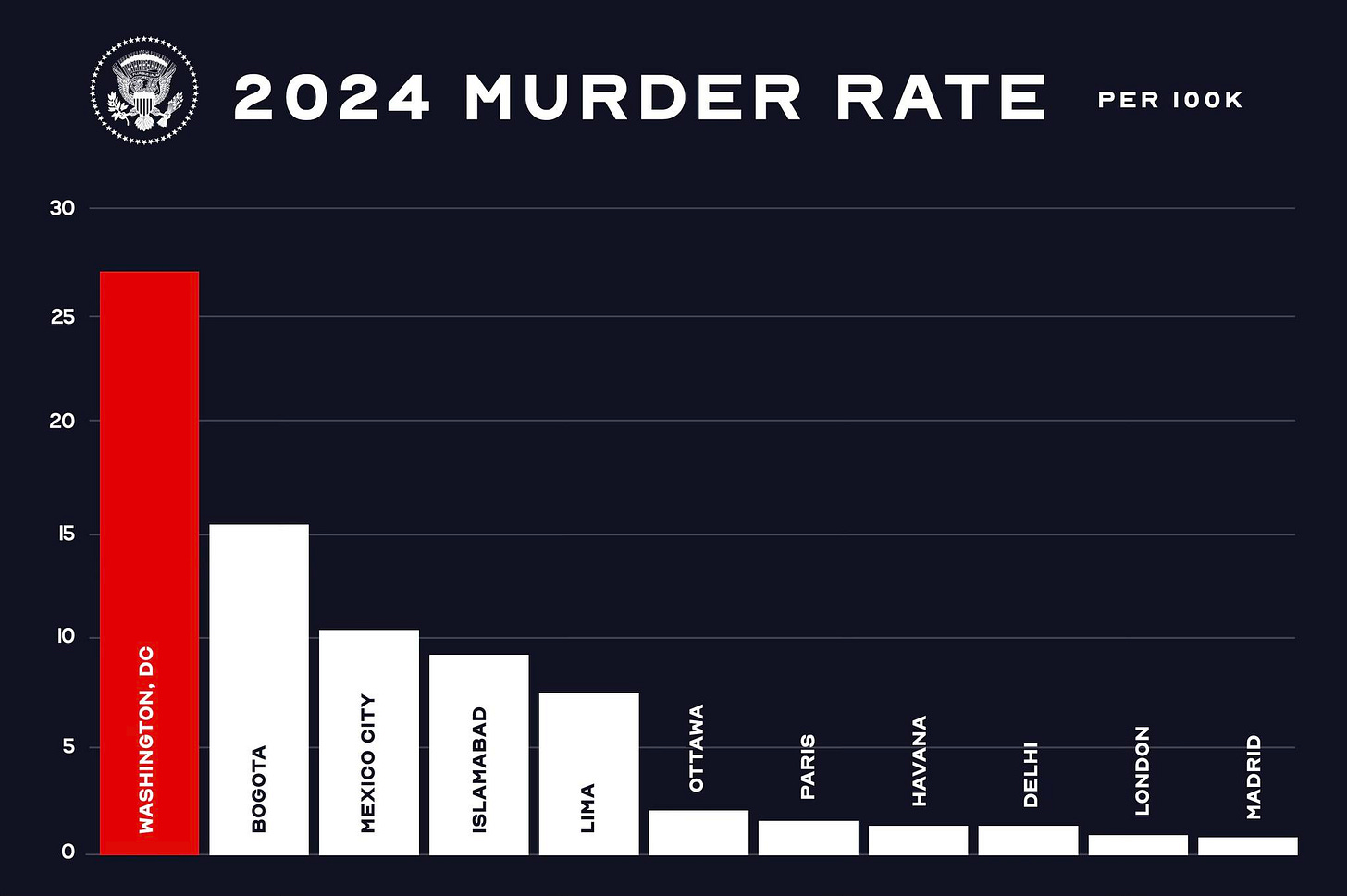

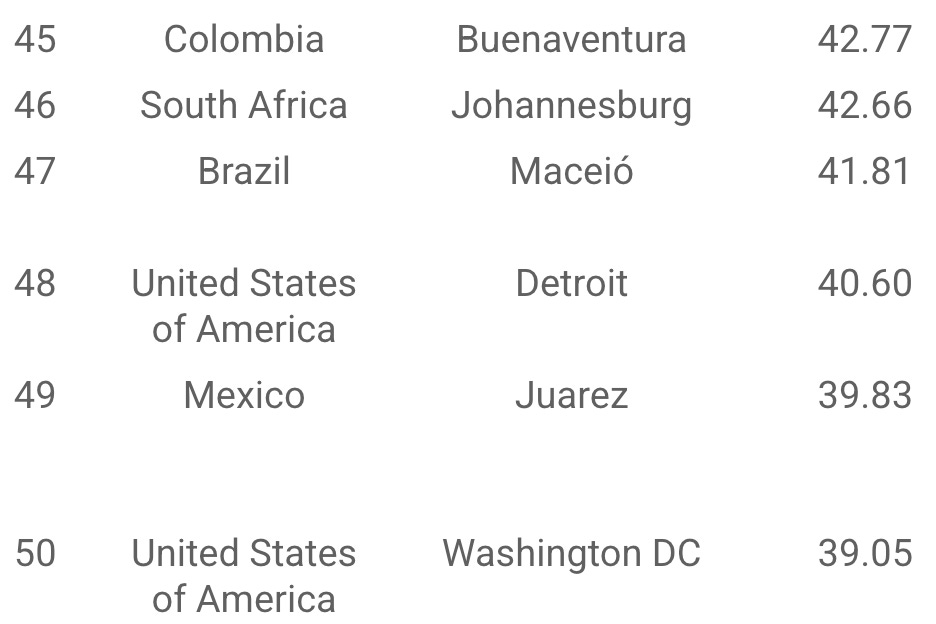

Trump also said “Look at the kind of numbers we have: D.C., 41 per 100,000, No. 1 that we can find anywhere in the world. Other cities are pretty bad, but they’re not as bad as that.”

This is partly right. There were 40.4 murders per 100,000 people in DC in 2023. However, this declined to 26.6 in 2024 and is on track to be even lower in 2025. Trump (deliberately?) chose numbers from the peak of the post-2020 crime spike.

The White House also showed a chart comparing DC’s 2024 murder rate to other capital cities:

These numbers are accurate, but again cherry-picked. DC is hardly “#1 that we can find anywhere in the world.” In 2023 it ranked #50 on a list of the most dangerous cities by homicide rate.

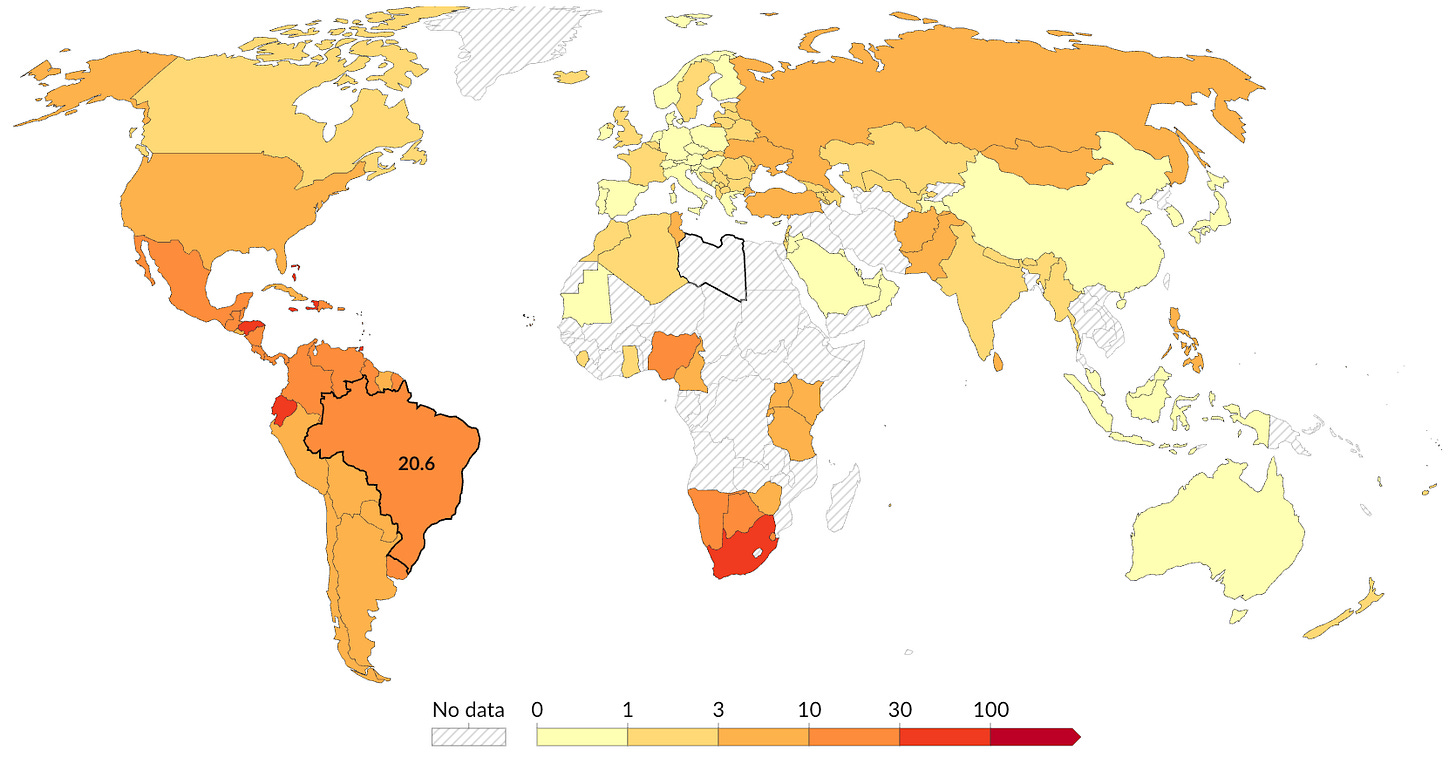

In terms of American cities, DC is somewhere the middle in terms of violent crime rate. However, in a global context, America is not a particularly safe country. The American homicide rate is generally lower than South America and African countries, but higher than European and Asian countries.

So is DC a crime-ridden city? By both American standards and global standards, it’s somewhere in the middle of the pack. Clearly, it’s possible to do better, but the long term trends are in the right direction.

Can we trust the numbers?

Given that Trump just fired the head of the Bureau of Labor statistics after the jobs numbers made him look bad, we can no longer assume broad trust in government statistics.

There is an argument in Red discourse that DC crime stats have been faked. This isn’t entirely unfounded: the police department just settled a case where an officer claimed that her superiors ordered her to misclassify crimes as less serious than they actually were, in order to make the stats look better. The alleged wrongdoing was from 2019 and the transcripts discuss thefts, not homicides — which are, after all, hard to cover up — so it’s not clear how this would affect recent DC murder statistics.

However, we do have an independent check on reported crime rates: comparison of police reports with victimization surveys (where people are directly asked if they’ve experienced a crime). That provides at least some check on data manipulation, and generally the two methods do match nationally. However, a) this check doesn’t include murder rates because you can’t survey someone who’s dead and b) we haven’t been able to find an analysis of these two data sources for DC in particular.

These sorts of problems with crime statistics are worth noting, and it’s angering Red readers that Blue publications are ignoring these potential issues. For example the Guardian stated that “[Trump] also baselessly accused DC law enforcement officials of giving ‘phony crime stats’ and said ‘they’re under investigation’”. The President is correct here — though it’s not clear whether it matters, and he’s also citing the same stats he criticizes as proof that there’s a crime problem.

Crime is hyper-local

Even if we could agree on definitions, topline numbers can miss the point. Crime clusters in predictable ways that make citywide statistics irrelevant to daily life, allowing for falling indicators and stubborn hotspots to coexist.

Criminologists call it the law of crime concentration: in city after city, a very small share of city streets account for a very large share of incidents, and that pattern stays surprisingly stable over time. In Seattle, for example, about 50% of all crime over 14 years occurred on roughly 4-5% of all blocks; similar concentrations show up in other U.S. cities and abroad.

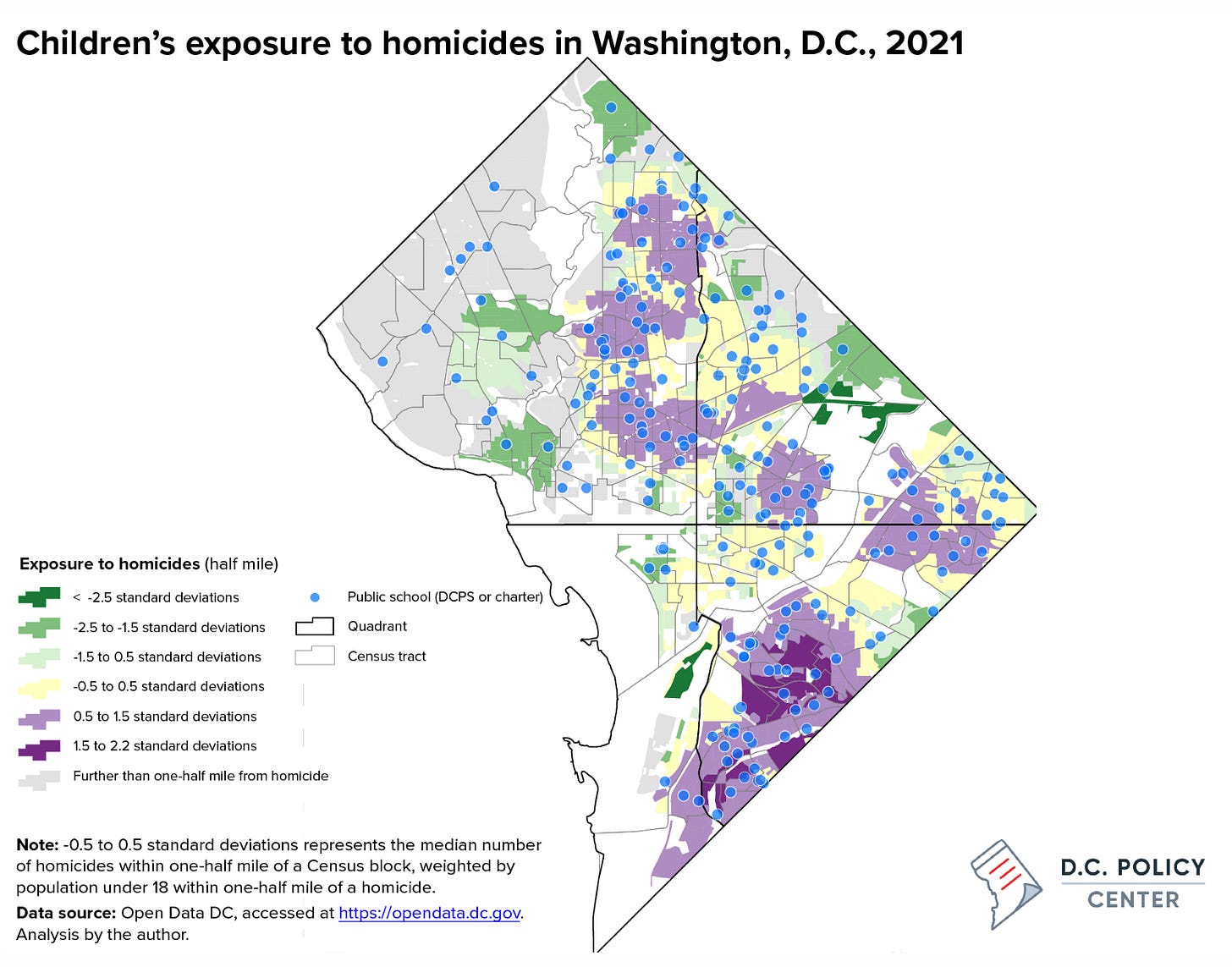

DC fits this pattern perfectly. In 2023, the top 10% of DC blocks still accounted for 46% of all crime. A separate mapping exercise shows sharp neighborhood disparities in children’s exposure to homicides.

If your commute crosses those hot spots, your reality is “crime is everywhere” even when citywide numbers are falling. For residents in these concentrated areas, crime isn't a perception problem, it's a daily reality that affects where they walk, when they go out, and how safe their children feel.

A mother who was mugged last month doesn't care that citywide crime fell 20% this year. Last week we covered how ethnic minorities in the U.S. are increasingly voting Republican, in large part because decreasing percentages feel irrelevant when their daily reality involves repeated victimization. Their experiences matter for policy, even if they don't show up in the year-end statistics politicians cite.

This is why both “crime is down” and “crime is a crisis” can be simultaneously true.

Different framings, different solutions

Broadly speaking, Red and Blue have very different ideas of both the causes and solutions to crime. Red sees crime as a problem of individual choice and accountability, and favors increased enforcement and harsher punishment. Blue is more likely to blame social factors like poverty, and favor rehabilitation and other supportive measures.

The truth, as always, is something of both. Increased policing does reduce crime. And because crimes are disproportionately committed by a small number of people, putting more of the worst offenders in prison would reduce crime simply by preventing them from committing more. However, the US already has a greater percentage of its population incarcerated than almost any other country in the world. Putting more people in prison may be politically, economically and morally unpalatable even to the most hardened law and order voter. As Scott Alexander put it in his exhaustive deep dive:

That means a real Three Strikes law would require increasing the incarceration rate from its current 0.75% up to 4%, ie quintupling it. We’d need to build 6,000 new prisons and 10,000 new jails, locking up an additional 5-10 million people, and spending somewhere between $400 billion and $1 trillion per year (ie around the same as the entire military budget) on prison-related costs. This is light-years outside the Overton Window and I’ve never heard anyone seriously propose it.

Still, it would decrease crime by 80%.

Yet prison does not and cannot address the root causes of crime. Contrast the American approach with the Finnish model, which sees prison as rehabilitative, where inmates can leave for school or jobs:

“Every piece of legislation, which is drafted on criminal justice, is prepared by civil servants who have a strong research background,” said Tapio Lappi-Seppälä, a professor of criminal law and criminology at the University of Helsinki.

The leading scholar said very few politicians in Finland build their political career around crime. And 1960s research found “we could really anticipate and assume that even if we do major changes with our prison system, that will not have a serious effect on the crime rates.”

Open prisons give inmates contact with the outside world and an environment that makes it easier to transition back into society. Lappi-Seppälä said taking away someone’s liberty is punishment enough.

So will Trump’s DC crackdown reduce crime? It might. Will this be worth the economic and human costs of increased incarceration? Maybe. Will it address the root causes of crime? Certainly not.

What about federalizing the cops though?

Whatever your politics, one can safely say it’s a continuation of the concentration of power under Trump. Federal control of the DC police is legal under emergency powers for up to 30 days. Trump has said he will seek “long-term” control over the police, but that would require Congress to repeal the Home Rule Act.

The darkest interpretation of Trumps’s quest to control DC policing is that he wants to be able to suppress protests against him, for example if he once again refuses to leave office. The most positive interpretation is that Trump really believes changing police policy will make the city safer. Perhaps the most likely case is that he’s most concerned to be seen to be tough on crime.

A better discussion about fighting crime

Real progress requires precision: specify which crimes, in which places, over which time periods. Then argue about solutions knowing you're solving the same problem. Targeting specific blocks and problems does seem to work better than broad approaches, but only when done with tactics that respect the communities involved.

The stakes here go beyond policy debates. When we can't agree on basic definitions, we lose the ability to evaluate whether interventions actually work. Federal troops in DC might reduce certain crimes in certain areas for certain time periods, but without clear metrics, it becomes impossible to know if it helped the people who actually live there. Meanwhile, the communities that need real solutions get caught between competing narratives from politicians who might not actually care about them.

The tragedy isn't that Americans disagree about crime policy. It's that we've made productive disagreement impossible by systemically failing to define what we're actually talking about.

Quote of the Week

I want to host a “MAGA + libs” party where the two sides are not allowed to talk politics. Instead they do an activity, like boardgames. I want to witness the dawning horror as they find themselves getting along

The attitude and tone of the Democratic Party will only continue to reinforce more people to vote against them. https://torrancestephensphd.substack.com/p/the-limousine-liberal-syndrome-strikes

Mike Gill was unavailable for comment. You ignore a lot of data that shows several forms of violent crime are up, and you completely ignore how the data has been corrupted in the District of Columbia. Do better. https://kellyjohnston.substack.com/cp/170783986

https://jonathanturley.org/2025/08/12/lies-damned-lies-and-statistics-trump-takeover-renews-questions-over-d-c-crime-data/