53 Roles That Make Democracy Work, and The People In Them — BCB #120

A sprawling new report from Beyond Intractability charts the web of roles that underpin healthy democracies—and who is doing what today

Last month, the Toda Peace Institute published a mammoth paper by Heidi and Guy Burgess (authors of Beyond Intractability and friends of BCB) that expands on a concept that the Burgesses have been developing for a long time, “massively parallel peacebuilding”:

Taken from the computer term “massively parallel computing,” the notion is that the “solution” to failing democracy comes in the form of thousands or hundreds of thousands of different people and organizations, each working on their own little “thing,” which together add up to a massive societal response to all the various challenges democracy faces. Rather than being a hypothetical theoretical idea, massively parallel problem solving is already happening on the ground—on a surprisingly large scale.

This new report does two things. First, it shows how the many problems facing healthy democratic functioning intersect—from polarization to free speech to discrimination to electoral integrity—and names the roles that address each issue.

Second, it lists many of the people and organizations already working in this space. It’s a who’s who of the field of American democracy-building, and pretty much everybody we’d want to invite to a conference (or better yet, a party).

What can be done for democracy?

One function of democracy — perhaps the core function — is to resolve disputes about governance. In the Burgess’ view, a democracy is healthy to the degree that it can perform a number of critical conflict resolution functions:

Vision: Cultivation of a shared underlying vision for society that is capable of binding citizens (and non-citizen residents) together despite their many deep differences.

De-Escalation and De-Polarization: Limitation of destructive escalation and hyper-polarization dynamics that can make shared, democratic governance impossible.

Mutual Understanding: Promotion of mutual understanding through the effective use of a broad array of trust-worthy and trusted communication mechanisms.

Reliable Assessments: Reliable, fact-based and technical assessment of the nature and causes of societal problems and the advantages and disadvantages of alternative options for addressing those problems.

Collaborative Problem Solving: Utilization of collaborative problem-solving processes that are able to identify and take full advantage of mutually beneficial opportunities, to generate pragmatic solutions to intractable problems.

Equitable Processes: Equitable decision-making processes and institutions that resolve disputes in cases where voluntary, collaborative processes are unable to make consensus or compromise decisions.

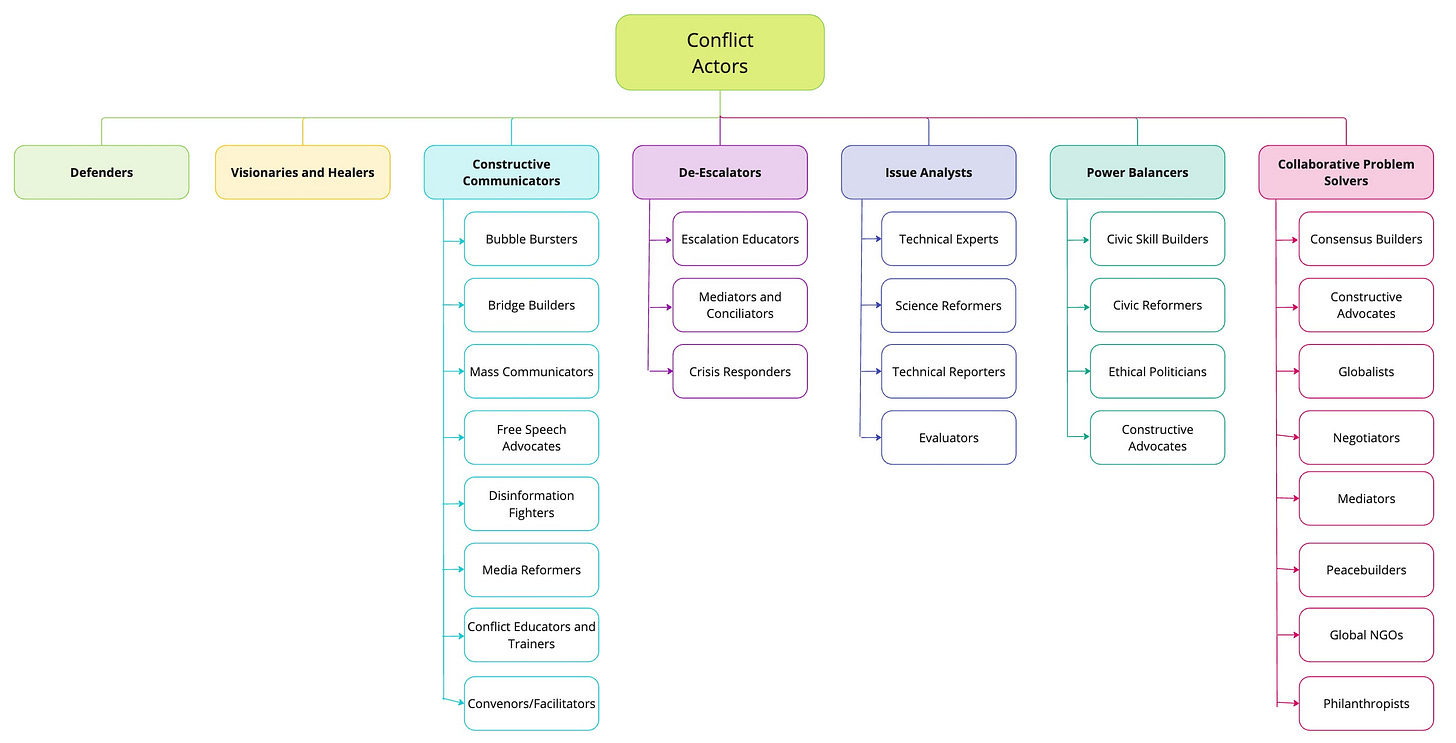

They then list 53 different roles that support these goals, that people and organizations can fill. The conflict strategists take on the “left brain” role of figuring out what needs to be done, while the conflict actors do the “right brain,” on-the-ground work of implementing ideas the strategists have come up with.

We mapped an earlier iteration of this framework in a BCB issue last January. The new report is a readable summary of the Burgess’ current thinking, but the definitive reference is the four part series they wrote in the spring (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4).

Who’s doing what today?

The Burgess’ map is not just theoretical. Rather, they include a lengthy list of people and organizations working in each of these roles.

For example, they cite Amanda Ripley, a name that is likely familiar to BCB readers, as an example of a “complexifier,” someone who does the strategic work of helping us “get beyond the cognitive biases that encourage us all to pursue simple answers and us-versus-them thinking, and instead, see our complex problems for what they really are.” The New Pluralists and the Liberal Patriot, meanwhile, are both “visionaries and healers,” who help people imagine what it would look like for disparate groups of Americans to coexist peacefully. And all of the following would be considered “constructive communicators,” or people “who communicate across difference in constructive ways and who can model and teach others to do the same”:

Bubble Bursters such as AllSides, who work to get people out of their narrow information bubbles,

Communication Skill Builders such as Essential Partners, who train people to use dialogue to help “build relationships across differences to address their communities’ most pressing challenges,

Bridge Builders such as Braver Angels and Living Room Conversations, which try to help people build bridges and understanding across divides,

Mass Communicators such as Search for Common Ground which has successfully used soap operas to teach peace and conflict resolution skills (although they are not yet doing this in the United States),

Free Speech Advocates such as FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression) and the Institute for Free Speech,

Convenors/Facilitators such as The National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation (NCDD), a very large network of organizations that convene processes to help people better understand each other, the challenges they face together, and how best to work together to address those challenges,

Disinformation Fighters such as AllSides and Ad Fontes Media that report on media bias and Comparitech which monitors censorship,

Media Reformers such as the Solutions Journalism Network which helps journalists cover problems fairly and in depth, focusing on solutions, not divisions, and

Conflict Educators and Trainers who help people engage in conflict more constructively.

The argument underpinning this massively parallel framework is that it takes a wide array of organizations and individuals working on fairly discrete tasks to keep democracies healthy and functional – and in fact, there are already people working on all of these things! As the Burgesses write:

together, these “little things” can build on and reinforce each other, such that the entire system starts to become more effective. And once innovations become valuable locally, the pressure to institute similar changes at the national level will grow. Ideally, that will enable leaders and their constituents to work together much more effectively than they do now. This, in turn, will enable most everyone to work together to start addressing our myriad substantive challenges including immigration, climate, health, education, inequality, and racism.

Quote of the Week

Civic participation is a relatively straightforward ask. It's a low lift. You can engage a lot of people through that. Bridging is a more complex ask because you're asking people to challenge their emotions and their points of view. Engaging in deliberative policy discussion is harder still. Then you have to engage with not only a civilized and fair discussion, but engage with the information and policy questions as well. And then comes the question of what do you do with these recommendations? And that's when it becomes important to act on them.